Under Confinement![]()

19 April 2020

A curator’s tour of Dwellings by Jess Boyce and Miranda Johnson

The Lobby

A curator’s tour of Dwellings by Jess Boyce and Miranda Johnson

The Lobby

On 15 March 2020, with regulations soon to come into effect that gatherings would be limited to 500 people, we opened Dwellings at The Lobby. This seems unthinkable now, with that number reduced to two less than three weeks later and all galleries and cultural institutions closed by government order. Of course, we weren't at risk of attracting anywhere near 500 people to the home gallery in Swanbourne, but the small crowd that did gather felt different; no hugs of greeting, a quick pump of hand sanitizer before grabbing a drink. We had many conversations that day about how the exhibition and particular works took on a new meaning as we looked towards spending more time at home.

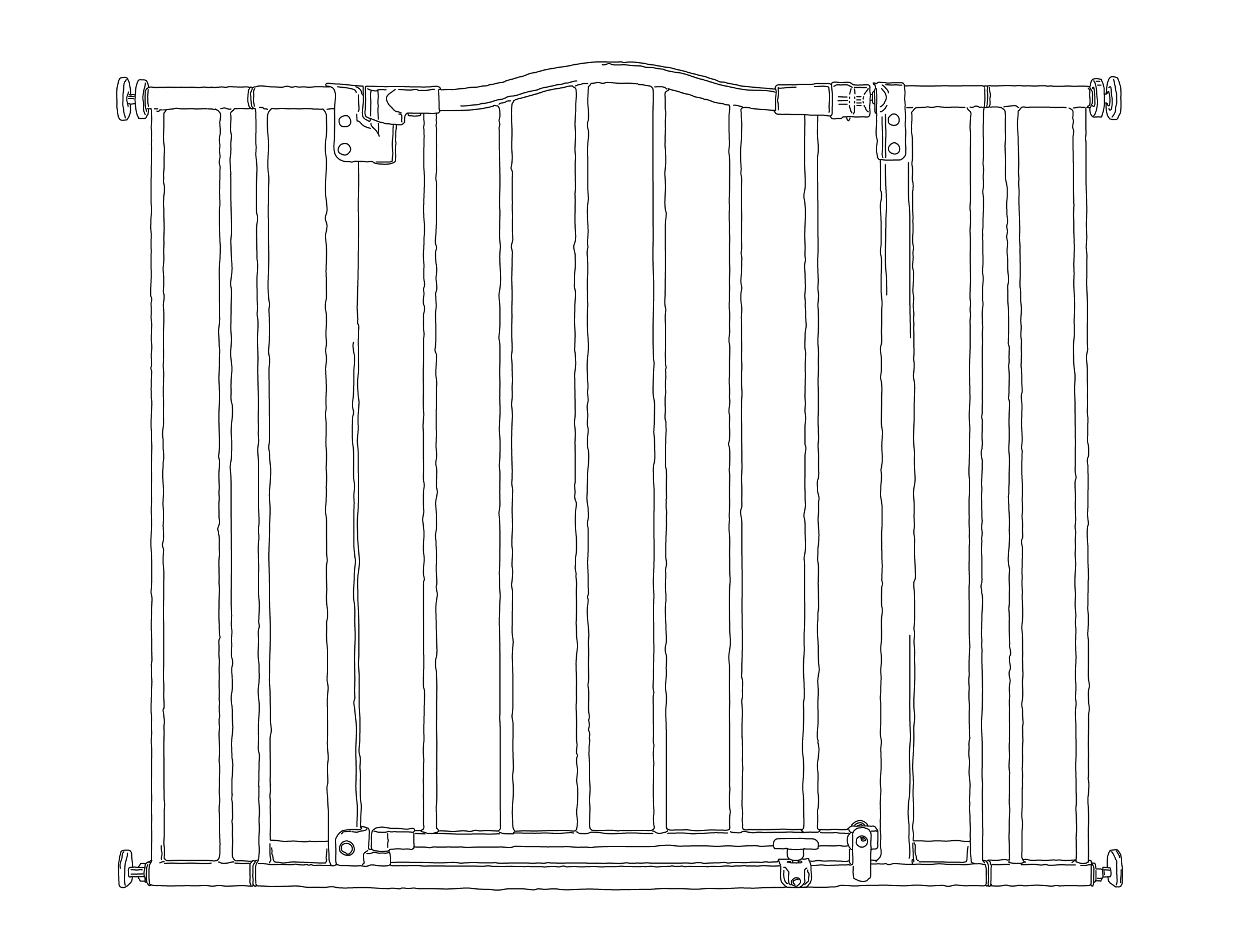

As the curators, the questions that we had hoped to explore through this exhibition were closely linked to the nature of the space itself. The Lobby straddles an interesting boundary between gallery and family home; a liminal space between personal and public. We were interested in how different audiences and participants navigated this space, as the home of the gallery’s Director Leah Robbie and her family. The artists and curators work in the space often around and within the circadian rhythms of family life - lunchtime, tv time, homework time, lazy weekend mornings spent in pyjamas; the new puppy whining plaintively from behind the baby gate that divides the gallery space from the family room.

After the opening event, exhibitions at The Lobby are viewable only by appointment. Home galleries are often limited in the kinds of audiences they can reach, due to their irregular opening hours and their location, often in the suburbs away from busy city centres. Moreover, entering someone’s home removes the comfort of anonymity that a public gallery space provides. As the seriousness of the pandemic unfolded, we discussed whether we should advertise that the space would be open. Should we even encourage people to visit, or should we quietly suggest that people stay at home, stay safe, not take any unnecessary outings? The in-between space of The Lobby began to feel even more unclear. What governmental guidelines should we follow here, those for private homes or public galleries?

We offer this text as an alternative tour of the exhibition as we look towards the coming months of restricted movement, isolation, and new ways of engaging with loved ones, belongings and art.

As the curators, the questions that we had hoped to explore through this exhibition were closely linked to the nature of the space itself. The Lobby straddles an interesting boundary between gallery and family home; a liminal space between personal and public. We were interested in how different audiences and participants navigated this space, as the home of the gallery’s Director Leah Robbie and her family. The artists and curators work in the space often around and within the circadian rhythms of family life - lunchtime, tv time, homework time, lazy weekend mornings spent in pyjamas; the new puppy whining plaintively from behind the baby gate that divides the gallery space from the family room.

After the opening event, exhibitions at The Lobby are viewable only by appointment. Home galleries are often limited in the kinds of audiences they can reach, due to their irregular opening hours and their location, often in the suburbs away from busy city centres. Moreover, entering someone’s home removes the comfort of anonymity that a public gallery space provides. As the seriousness of the pandemic unfolded, we discussed whether we should advertise that the space would be open. Should we even encourage people to visit, or should we quietly suggest that people stay at home, stay safe, not take any unnecessary outings? The in-between space of The Lobby began to feel even more unclear. What governmental guidelines should we follow here, those for private homes or public galleries?

We offer this text as an alternative tour of the exhibition as we look towards the coming months of restricted movement, isolation, and new ways of engaging with loved ones, belongings and art.

[continue reading below︎]

^^ Stephanie de Biasi, This Side Up, 2020.

The Lobby is a custom-made space within a domestic environment. Rather than responding to the quirks of an unrenovated property, or the antiquated fireplaces and floorboards of a rambling sharehouse home—as many other domestic galleries have done—The Lobby’s space is immaculately and thoughtfully devised to help visitors navigate the space; the entrance, hanging systems and the track lighting all designed to translate seamlessly to an exhibition context. You can’t enter the house without walking through the exhibition space. Go upstairs and you’re in the private realm of bedrooms and bathrooms—off limits to visitors. Navigate the hallway to its end and your journey concludes in the heart of the house; the kitchen and dining area, the backyard, the swimming pool and pizza oven. Exhibition space and home are seamlessly linked by design.

This Side Up is a collection of bright, primary coloured assemblages welcoming you at the door and following your journey through the gallery. This series of sculptural works investigate the disruption of routine and comfort within domestic spheres via Stephanie de Biasi’s recent process of minimising her accumulated belongings into a mobile home. Sponges and toy balls are squished into wooden frames, a bag, a pool blanket and a sun shade are wrapped neatly around boards. The push and pull between hard and soft feels like the stress of stuffing belongings into a box, the accumulation of objects too useful to be thrown out, too hard to recycle, but not essential enough to keep when you’ve got to travel light.

Nearby Madeleine Beech’s whimsical sculptures evoke a sentimentality toward her parents’ home through a mix and match of found objects and assemblages. A palette of rusting and tarnished metals, worn paint and timber alludes to these objects' past histories as she rearranges and constructs playful new associations. Tucked under the stairs in a space that is often reserved for storage of useful items, both de Biasi and Beech’s works suggest other ways to reorganise, assemble and relate to the objects that we share our spaces with. Now that we’re all confronting our belongings through the endless stretch of home confinement, what kinds of relationships will we form with them, these half-finished craft projects, old puzzles we never completed, and books that we meant to get rid of? How will we order, sort and rearrange our home lives to suit this new existence?

This Side Up is a collection of bright, primary coloured assemblages welcoming you at the door and following your journey through the gallery. This series of sculptural works investigate the disruption of routine and comfort within domestic spheres via Stephanie de Biasi’s recent process of minimising her accumulated belongings into a mobile home. Sponges and toy balls are squished into wooden frames, a bag, a pool blanket and a sun shade are wrapped neatly around boards. The push and pull between hard and soft feels like the stress of stuffing belongings into a box, the accumulation of objects too useful to be thrown out, too hard to recycle, but not essential enough to keep when you’ve got to travel light.

Nearby Madeleine Beech’s whimsical sculptures evoke a sentimentality toward her parents’ home through a mix and match of found objects and assemblages. A palette of rusting and tarnished metals, worn paint and timber alludes to these objects' past histories as she rearranges and constructs playful new associations. Tucked under the stairs in a space that is often reserved for storage of useful items, both de Biasi and Beech’s works suggest other ways to reorganise, assemble and relate to the objects that we share our spaces with. Now that we’re all confronting our belongings through the endless stretch of home confinement, what kinds of relationships will we form with them, these half-finished craft projects, old puzzles we never completed, and books that we meant to get rid of? How will we order, sort and rearrange our home lives to suit this new existence?

[continue reading below︎]

^^ Madeleine Beech, Metamorphosis, 2020 and Ferris Wheel, 2020; Halt, 2020.

The Lobby sits within a building of modern Australian architectural design, and a leafy Western suburbs context. Neighbours are friendly, popping into exhibition openings and chatting on the lawn, then returning to their own houses, the fences high enough to provide privacy and a sound barrier, the blocks large enough for everyone to have room for a backyard with a swimming pool. These structures are built to keep us separated from each other, providing personal space and privacy, whilst also negotiating enough connections to feel as though we can be part of a neighbourhood, a community.

Bookending the stretch of hallway and tucked in the stairwell are three small TVs displaying Tanya Lee’s multi-channel video work Curtilage. Straight faced neighbours have their hair or teeth brushed or are fed cereal with middling success by utensils on makeshift poles, an acceptable length of social distance extended between windows and balconies. The term curtilage can be understood as the view from your window, the extended space of a home that encompasses the immaterial equity of trees, sky, sun and, more often than not, a neighbour’s window or backyard, depending on your level of urban density. It’s these works that seem most prescient in these times, as neighbours perform domestic acts for one another, made ludicrous by distance. To have someone in reach when in need, the relationship and proximity between neighbours can be as valuable as privacy and a nice view.

Lee’s multi-channel works traverse a series of houses from a classic single-story 1930s cottage to blocks of unadorned 1970s brick flats - a utopian dream of high-density living that Perth never quite embraced. The patterns of the brick balcony exteriors in Lee’s work finds a focal point alongside it in Tom Freeman’s Bricks on bricks around brick. The enormity of suburban structures built to house us is reduced to a single part, lovingly made individual by the addition of its own ceramic exterior of tiny bricks. Layers upon layers of built environment nod to the multiple meanings found within the brick as both a utilitarian and art object. Within the structures made by these bricks, however, inequality is laid bare. Isolating in an apartment alone feels very different to isolating in a house with family, a backyard, pool, when parks and other public spaces are increasingly policed.

Bookending the stretch of hallway and tucked in the stairwell are three small TVs displaying Tanya Lee’s multi-channel video work Curtilage. Straight faced neighbours have their hair or teeth brushed or are fed cereal with middling success by utensils on makeshift poles, an acceptable length of social distance extended between windows and balconies. The term curtilage can be understood as the view from your window, the extended space of a home that encompasses the immaterial equity of trees, sky, sun and, more often than not, a neighbour’s window or backyard, depending on your level of urban density. It’s these works that seem most prescient in these times, as neighbours perform domestic acts for one another, made ludicrous by distance. To have someone in reach when in need, the relationship and proximity between neighbours can be as valuable as privacy and a nice view.

Lee’s multi-channel works traverse a series of houses from a classic single-story 1930s cottage to blocks of unadorned 1970s brick flats - a utopian dream of high-density living that Perth never quite embraced. The patterns of the brick balcony exteriors in Lee’s work finds a focal point alongside it in Tom Freeman’s Bricks on bricks around brick. The enormity of suburban structures built to house us is reduced to a single part, lovingly made individual by the addition of its own ceramic exterior of tiny bricks. Layers upon layers of built environment nod to the multiple meanings found within the brick as both a utilitarian and art object. Within the structures made by these bricks, however, inequality is laid bare. Isolating in an apartment alone feels very different to isolating in a house with family, a backyard, pool, when parks and other public spaces are increasingly policed.

[continue reading below︎]

^^ Tanya Lee, Curtilage, 2016. Tom Freeman, Bricks on bricks around brick, 2019.

^^ Beverley Iles, Tiny vessels, 2019; River Dyed I & II, 2020

Spattering news feeds recently are reports of nature reclaiming environments in the absence of human activity; schools of fish returning to the now clear waters of Venetian canals, deer wandering through suburban streets. Termites are dreaded invaders, reclaiming timber homes since we started building them, but alongside wasps and ants, they are creators of their own sophisticated structures. Remnants of these nests are utilised in Beverley Iles’ Tiny Vessels series, as well as wild clay sourced from her property and other sites that have undergone significant transformation due to the effects of industrialisation and colonisation; contaminated with heavy metals and remnants of past construction. Whilst it is nice to hope that the reduction in pollution and carbon emissions during this time of decreased activity will make a lasting impact when life returns to normal, it is sadly unlikely. As Iles’ work reminds us, contamination and industrial pollution seeps into the soil, changing the nature of the environment perhaps forever. On the opposite wall River Dyed I & II, eco-fabric pieces imprinted with clay from a riverbank, speak of ever changing boundaries, both physical and imagined; a meditation on the permanence (or otherwise) of home and place.

Unsettled relationships to places we call home; as well as the importance of biological and chosen families, are also explored in Aisyah Aaqil Sumito’s durational performance A Place to Reckon. The repeated pilgrimage Sumito undertook to their mother’s home is displayed as a series of glossy 6x4 photographs. Accompanied by a series of close friends who documented the performances, Sumito excavated items from the house including bricks, snow chains and copies of the Qur’an, carrying the bulky, heavy items via public transport to their studio to be reconfigured as an installation. This journey negotiated an awareness of the vulnerability inherent to occupying public space, our current situation means that leaving home is a risk, but it’s not a risk that is carried evenly, nor is it a new risk for many. Leaving home and appearing in public can be a privilege at the best of times.

Unsettled relationships to places we call home; as well as the importance of biological and chosen families, are also explored in Aisyah Aaqil Sumito’s durational performance A Place to Reckon. The repeated pilgrimage Sumito undertook to their mother’s home is displayed as a series of glossy 6x4 photographs. Accompanied by a series of close friends who documented the performances, Sumito excavated items from the house including bricks, snow chains and copies of the Qur’an, carrying the bulky, heavy items via public transport to their studio to be reconfigured as an installation. This journey negotiated an awareness of the vulnerability inherent to occupying public space, our current situation means that leaving home is a risk, but it’s not a risk that is carried evenly, nor is it a new risk for many. Leaving home and appearing in public can be a privilege at the best of times.

[continue reading below︎]

^^ Aisyah Aaqil Sumito, A place to reckon (documentation), 2018-2019; ku bakar jambatan, 2019. Esther McDowell/Yabini Kickett, Korel (Shells), 2020.

As we adjust to more and more restrictions on our daily lives, a sense of barely concealed outrage seems to have settled over the Australian public. Not being able to go to the beach, eat a kebab on a bench, or go down south for Easter chafes at the collective sense of entitlement to this land. Enjoying public spaces and the natural environment has long been seen as a quintessential Aussie pastime, but restriction of movement is much more deeply embedded into the DNA of white Australia than the beach, BBQ and beers. This colonial manner of enjoying this land finds a quiet counterpoint in Esther McDowell/Yabini Kickett’s eco-dyed linen squares meticulously decorated with tiny shells collected from the beach. McDowell/Kickett’s work speaks to the feelings of devastation due to loss of ancestral country, whether through limitations of movement and theft of land by colonial invaders, or through ongoing environmental devastation masked as ‘progress’.

These recent restrictions on movement and ways of living, often referred to as ‘unprecedented’, are of course nothing of the sort. We must not forget Perth’s laws stopping Indigenous people from entering the CBD, often violently enacted through police brutality. Or the iron-tight control over Australian borders, turning people away in false pretence of preventing deaths at sea, to instead detain innocent people in offshore prison camps to distance them from our responsibility. There are both historical and current precedents for our current situation, just not ones that people are particularly keen to acknowledge or remember.

Dwellings opened amidst a sense of the ground shifting under our feet, destabilising many foundational ways of living and being. The works in the exhibition speak to the duelling forces of safety and exclusion, asking questions about how we experience intimacy, refuge, and solace. But limitations and restrictions on our ways of life, and the ways in which we relate to our homes and belongings, have always been shifting, contested, and unevenly distributed. Whether the current COVID-19 situation will lead to lasting change, either in our politics, our ways of gathering, or cultural experiences remains to be seen. Looking ahead to the impending weeks, months, years; these works also seem to gesture towards how we might experience the future, as the ways in which we live our lives under confinement turn inexorably inwards, towards the local and the personal.

These recent restrictions on movement and ways of living, often referred to as ‘unprecedented’, are of course nothing of the sort. We must not forget Perth’s laws stopping Indigenous people from entering the CBD, often violently enacted through police brutality. Or the iron-tight control over Australian borders, turning people away in false pretence of preventing deaths at sea, to instead detain innocent people in offshore prison camps to distance them from our responsibility. There are both historical and current precedents for our current situation, just not ones that people are particularly keen to acknowledge or remember.

Dwellings opened amidst a sense of the ground shifting under our feet, destabilising many foundational ways of living and being. The works in the exhibition speak to the duelling forces of safety and exclusion, asking questions about how we experience intimacy, refuge, and solace. But limitations and restrictions on our ways of life, and the ways in which we relate to our homes and belongings, have always been shifting, contested, and unevenly distributed. Whether the current COVID-19 situation will lead to lasting change, either in our politics, our ways of gathering, or cultural experiences remains to be seen. Looking ahead to the impending weeks, months, years; these works also seem to gesture towards how we might experience the future, as the ways in which we live our lives under confinement turn inexorably inwards, towards the local and the personal.

Dwellings

Madeleine Beech, Stephanie de Biasi, Beverley Iles, Tanya Lee, Tom Freeman, Esther McDowell/Yabini Kickett and Aisyah Aaqil Sumito

Curated by Jess Boyce and Miranda Johnson

The Lobby

15 March - 03 April, 2020

Image Credits :

All photos by Jess Boyce