Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair

06 October 2019

A response by Kelly Fliedner to Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair,

an exhibition by Agatha Gothe-Snape with the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art

Perth Institute of Contemporary Art

A response by Kelly Fliedner to Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair,

an exhibition by Agatha Gothe-Snape with the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art

Perth Institute of Contemporary Art

[TITLES]

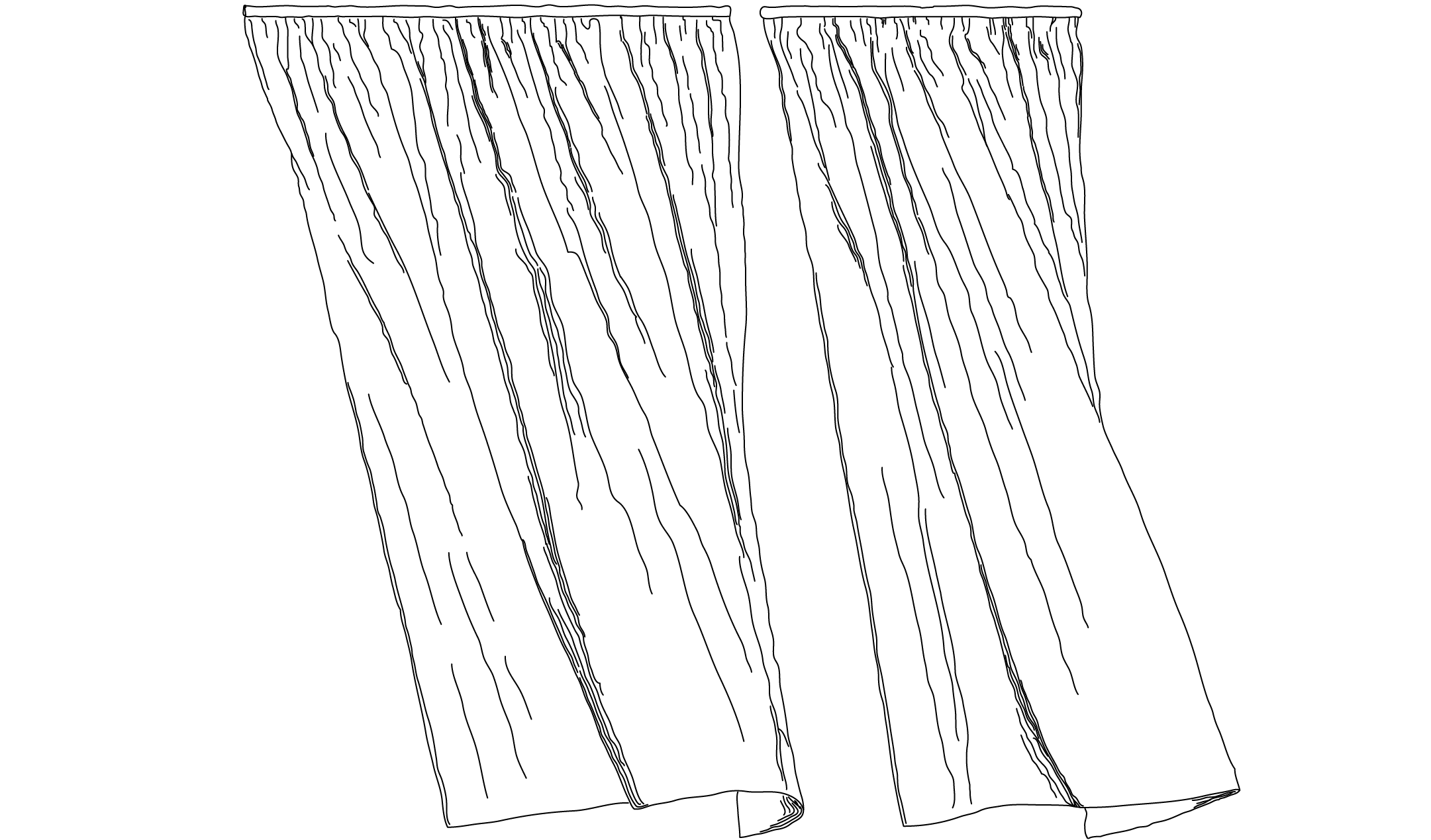

Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art is the result of an invitation extended to Agatha Gothe-Snape to respond to, and critically engage with, the University of Western Australia’s Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art. It includes a combination of works from the collection including Gothe-Snape’s own Certain Situations/EXPRESSION CURTAIN (2013); new research drawings and text-based works by Gothe-Snape in response to the collection; a grouping of 14 chairs borrowed from various artists in the collection at the invitation of Gothe-Snape; a series of letters from Gothe-Snape that extended that invitation to those artists; and, various ephemera connected in some way to the collection or the gathered chairs.

Each of these components act as connecting nodes, revealing in various ways the research interests and practice of Gothe-Snape, and illustrating her own workings with the collection as she built toward the exhibition itself. Chronologically, this research might start with We Must Risk Unlearning (2018) an initial sketch that includes a list of titles of works in the Cruther’s Collection including the eponymous work by Ann Newmarch, We Must Risk Unlearning (1975) (not in the exhibition), a screen-print that interrogates, through collaged mass media imagery, the white female body. In Gothe-Snape’s sketch, the list of titles run down the centre of the work with radiating lines connecting to their appropriate artists names and dates so that the page appears as a schematic representation of her own desire lines weaving through the collection.

This linking as a first stage of categorisation indicates just how important the Cruthers Collection is as a document of the history of women’s practice in Australia (it includes key figures from not only Western Australia but across the continent including Fiona Foley, Lizzie Newman, Rosalie Gasgoin, Grace Cossington Smith, Elizabeth Durack, Linda Marrinon, Vivian Shark Le Witt, Julie Dowling, Narelle Jubelin, Margaret Preston, and Judy Watson etcetera).

The collected titles of We Must Risk Unlearning also begin to betray the core interests of the Collection itself, and by virtue the continued collective concerns of women artists across generations. For instance: gender, bodies, race (‘Standing Nude’, ‘Girl in a Corner’, ‘Haircut’, ‘Native Blood’, ‘Wudjuta Yorgan (White Woman)’; romance (‘Folly Love’, ‘Anything Your Heart Desires’); the domestic (‘The Kitchen Sink’, ‘Christmas Dinner’, ‘Kitchen Still Life’; and, landscapes, flora, floral (‘Mixed Bunch’, ‘A Rose is a Rose’, ‘Red Blossom’).

Not only do these titles act, for Gothe-Snape, as initial entry points into the collection, they also become a strategy for directing the audience through the exhibition. They become stage directions for the audience; instructions indicating how they might read a work, how they might position themselves in relation to the exhibition; breadcrumbs left for those seeking paths through the research and final installation.

These titles are generative for Gothe-Snape in manifold ways. We_Must_Risk_Unlearning.pptx (2018) is a looped series of Microsoft PowerPoint Presentation slides featuring the same titles of We Must Risk Unlearning.

Arranged anew, like the bouquets of flowers that surround it (a nearby wall features A Rose is a Rose (1986-88) by Rosalie Gascoigne and Hakea in Landscape (c.1984) by Miriam Stannage) the work alludes to particularly normative views on gender and how that relates to the creation of art, and understanding of landscape. All the while undermining such expectations by presenting the text through the cold, corporate, potentially masculine, definitely not floral, platform of PowerPoint.

Not only do these titles act, for Gothe-Snape, as initial entry points into the collection, they also become a strategy for directing the audience through the exhibition. They become stage directions for the audience; instructions indicating how they might read a work, how they might position themselves in relation to the exhibition; breadcrumbs left for those seeking paths through the research and final installation.

[BOUQUETS]

These titles are generative for Gothe-Snape in manifold ways. We_Must_Risk_Unlearning.pptx (2018) is a looped series of Microsoft PowerPoint Presentation slides featuring the same titles of We Must Risk Unlearning.

Arranged anew, like the bouquets of flowers that surround it (a nearby wall features A Rose is a Rose (1986-88) by Rosalie Gascoigne and Hakea in Landscape (c.1984) by Miriam Stannage) the work alludes to particularly normative views on gender and how that relates to the creation of art, and understanding of landscape. All the while undermining such expectations by presenting the text through the cold, corporate, potentially masculine, definitely not floral, platform of PowerPoint.

These themes that emerge through the titles of the works in the Cruther’s Collection of course gesture to conventional gender normative subject matters for women artists. But that is definitely not to say that the Collection or the works within it necessarily perpetuate those themes, instead they recognise and often actively subvert these restricting expectations. In A Rose is a Rose, Gascoigne literally deconstructs two images of roses, one yellow, one pink, and like a large muddled puzzle incoherently rearranges them so that out of the building blocks of flowers she constructs a gridded, postmodern, pop-culture abstraction — alluding to the artifice or incompleteness or simply the limitations of a flower as a representation of anything let alone the role and place of women artists.

Another example of these unexpected botanical arrangements is Mei Swan Lim’s two audio works Sky Life (2008) and Ground Life (2008), both pieced together from field recordings of Perth’s various natural and unnatural bush and wetlands such as Piney Lakes Reserve, Baigup Wetlands, and the Beeliar Wetlands. The looped works present an aural portrait of Perth as a collision of constructed and unconstructed space and of native and introduced species. The recordings including the honeyeater, wren, wattlebird, crow, magpie, bee and cricket with the occasional nearby car or overhead plane. Lim’s works place her within a history and lineage of Cruthers Collection artists interested in botanical and floral arrangements, but using the medium of sound reminds us that these parameters are forever open to interpretation, that we do not need to stick within the lines, that we can forge our own course through the subjects bestowed us.

Another example of these unexpected botanical arrangements is Mei Swan Lim’s two audio works Sky Life (2008) and Ground Life (2008), both pieced together from field recordings of Perth’s various natural and unnatural bush and wetlands such as Piney Lakes Reserve, Baigup Wetlands, and the Beeliar Wetlands. The looped works present an aural portrait of Perth as a collision of constructed and unconstructed space and of native and introduced species. The recordings including the honeyeater, wren, wattlebird, crow, magpie, bee and cricket with the occasional nearby car or overhead plane. Lim’s works place her within a history and lineage of Cruthers Collection artists interested in botanical and floral arrangements, but using the medium of sound reminds us that these parameters are forever open to interpretation, that we do not need to stick within the lines, that we can forge our own course through the subjects bestowed us.

[continue reading below︎]

^^^ images by Bo Wong

[CHAIRS]

Of these subjects, Gothe-Snape’s research congeals around five distinct themes that are revealed in a series of 15 yellow letters: ‘titles, bouquets, chairs, holes, and curtains’. These letters sent to various recipients ask for permission to exhibit key works and loan items for the exhibition, while also acting as a device to extrapolate upon the research project and Gothe-Snape’s relationship to it for the broader exhibition audience. The letters reveal in sometimes intimate ways (particularly when she is addressing another artist) the anxieties of Gothe-Snape around the process of being collected as an artist and the feeling of being at once grateful and cautious of letting go of control of a work’s reading or display.

It seems that one of the ways that Gothe-Snape finds comfort is through the forwarding on of that original invitation to participate. She becomes the facilitator of further engagement and opens up the project so that it perpetually feels as if it’s scattered outward. Nothing is stagnant. Not even these five themes are easily cordoned off, and in fact undergo slight variations and mutations in the letters themselves (for instance ‘BOUQUET’ is sometimes written as ‘FLOWERS’). Additionally these themes are not always literal; yes works depict chairs, holes and curtains, but the exhibition is also equally concerned with what these objects and subjects say figuratively about the complex networks of relations and ideas that swirl around the collection and the art world at large. Yes, the chair is subject and object of the Collection, and it is literally depicted as such in many works included in Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair. But what of the figurative chair?

In Anne Newmarch’s screenprint Women Hold Up Half the Sky (1978) a woman gleefully holds up an even happier looking man, while in Giles Hohnen’s Waiting for Harry (1984) (the only work by a man in this exhibition) depicts Hohnen’s pregnant wife, artist Evelyn Kotai knitting and waiting. Both works in different ways gesturing to the female body as infrastructure, as supporting device, as incubator, as both comfortable and uncomfortable chair. In this sense these chairs connect to other items of stage infrastructure and support mechanisms that feature across the exhibition including the propped billboard screen that the bouquet-like We_Must_Risk_Unlearning.pptx is projected upon, or the Certain Situations/EXPRESSION CURTAIN, a window, curtain and small laser-print text-based work at the entrance of the exhibition that is held up by a large and relatively elaborate structure built from the same materials as the plinth that props up the collection of chairs.

This is all to say that no work in the exhibition is easily filed into one or another category, instead everything gestures at multiple themes and connects across the space, creating a network of interconnection, an ecosystem or rhizome that radiates out from the Cruther’s Collection but that does not find either an end or beginning within the Collection.

This is all to say that no work in the exhibition is easily filed into one or another category, instead everything gestures at multiple themes and connects across the space, creating a network of interconnection, an ecosystem or rhizome that radiates out from the Cruther’s Collection but that does not find either an end or beginning within the Collection.

[continue reading ︎]

^^^ images by Bo Wong

[HOLES]

Artists have a good knack for finding the holes within collections and it has therefore become common practice for artists to be invited to engage in archival and collection research as a way for various collections to address their own shortcomings. These kinds of projects become an act of invitation as necessary act of self critique; are a way to bring or realign an original concern of a collection into a contemporary moment; a way to rethink and update an original vision; a way to unsettle an original concern or politic.

So what is unsettled by Gothe-Snape? Through the recitation of these well worn women’s themes do we come to some conclusion about the contemporary use value of a women’s art collection? Or has that urgency intersectionally shifted?

At no point do any of the ‘holes’ of the exhibition feel like negative space, empty mistakes, or voids that needs to be filled. Instead the ‘holes’ are generative. They gesture to new paths, continuously growing and connecting to parts outside themselves. They are necessary vacancies for in- and exhalation. There is comfort too, in the recognition of ‘holes’. Finding a place to insert yourself where no one bothered to be before. Holes as refuge places to escape to; as dots waiting to be joined; as spaces ready for new narratives of self-recreation; as places to craft new strategies for being.

Exit Strategies (2018-19) by Gothe-Snape is made of two components: the first being an empty golden frame once home to Elise Blumann’s Self Portrait (1937); the second, a photograph of Lake Monger (c. 1914) by Louis Shapcott.

Blumann’s portrait was one of the first works acquired by the Cruthers and features herself before a body of water. When they collected the work, Blumann suggested that it was Lake Monger when in actuality it was painted while Blumann and her family were still in Essex en route from Nazi Germany waiting to move onto Australia; an example of the necessary tales one tells, not only to interest a collector and sell a work of art, but also forge connection to place where there was none before. The dissonance between reality and fiction further complicated by the fact that the photograph by Shapcott of the actual Lake Monger features a remarkably similar looking sailing boat to that behind Blumann. Maybe it was Lake Monger after all?

Of course the actual Blumann Self Portrait does not feature in Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair. Instead we have it’s previous, now uninhabited, home featuring four meshed openings as breathing space for the once encased work. It’s inclusion, along with the photograph, are a ghostly cipher for the original which is on concurrent display in another exhibition, Cosmopolitan, a gathering of Cruther’s Collection works from the oft forgotten 1930s at Lawrence Wilson Gallery. PICA brought into direct conversation here and now with Lawrence Wilson all the way across the city, through the cultivated and uncultivated expanses of King’s Park to The University of Western Australia.

Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair takes pleasure in and wallows in the potential conversations and happenings that take place in and across voids — across holes — and rewards the audience willing to look for them. Once you realise they are there, they are everywhere.

Of course the actual Blumann Self Portrait does not feature in Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair. Instead we have it’s previous, now uninhabited, home featuring four meshed openings as breathing space for the once encased work. It’s inclusion, along with the photograph, are a ghostly cipher for the original which is on concurrent display in another exhibition, Cosmopolitan, a gathering of Cruther’s Collection works from the oft forgotten 1930s at Lawrence Wilson Gallery. PICA brought into direct conversation here and now with Lawrence Wilson all the way across the city, through the cultivated and uncultivated expanses of King’s Park to The University of Western Australia.

Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair takes pleasure in and wallows in the potential conversations and happenings that take place in and across voids — across holes — and rewards the audience willing to look for them. Once you realise they are there, they are everywhere.

For instance that frame and its paired photograph are not merely arranged on the wall next to or even near each other, they speak across the literal void and opening of PICA exhibition space, into once of its ancillary rooms. In that room are a collection of Cruthers works that explicitly feature holes as both negative spaces and circular motifs not as formal end points but as spaces to be moved through and beyond.

Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair is the kind of exhibition that rewards those who are prepared to participate in the shifting, categorising and comparing that Gothe-Snape has undertaken herself to bring these objects together. There is reward to be found in reading each of the wall labels, every letter and text-based work, and really looking at the art objects presented. I found much satisfaction in the slight shifts and connections across the exhibition but was also overwhelmed at times by the spiraling out of association that took me from PICA and plunged me into a sprawling collection that is constantly evoked but often not present.

Not unlike the role of Lady Sheila Cruthers as founding collector of the Cruthers Collection, Gothe-Snape’s presence is one of receding mediator. As the director of this exhibition stage, she brings all these artworks together, sets the scene, organises the parameters, arranges the props, brings the actors together, blocks them into position, gathers an audience and then lets the work unfold of its own accord, but not in isolation. Engagement with this exhibition is to become one of Gothe-Snape’s players, moving across the stage, in need of a little support, simultaneously supporting each other, across a threshold, toward a conclusion.

[CURTAINS]

Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair is the kind of exhibition that rewards those who are prepared to participate in the shifting, categorising and comparing that Gothe-Snape has undertaken herself to bring these objects together. There is reward to be found in reading each of the wall labels, every letter and text-based work, and really looking at the art objects presented. I found much satisfaction in the slight shifts and connections across the exhibition but was also overwhelmed at times by the spiraling out of association that took me from PICA and plunged me into a sprawling collection that is constantly evoked but often not present.

Not unlike the role of Lady Sheila Cruthers as founding collector of the Cruthers Collection, Gothe-Snape’s presence is one of receding mediator. As the director of this exhibition stage, she brings all these artworks together, sets the scene, organises the parameters, arranges the props, brings the actors together, blocks them into position, gathers an audience and then lets the work unfold of its own accord, but not in isolation. Engagement with this exhibition is to become one of Gothe-Snape’s players, moving across the stage, in need of a little support, simultaneously supporting each other, across a threshold, toward a conclusion.

Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair

— Agatha Gothe-Snape with the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art

Perth Institute of Contemporary Art

27 July – 6 October 2019

With works and contributions from: Elise Blumann, Penny Bovell, Angela Brennan, Susanna Castleden, Penny Coss, Janet Dawson, Helen Eager, Rosalie Gascoigne, Helen Grace, Giles Hohnen, Narelle Jubelin, Eveline Kotai, Maria Kozic, Mei Swan Lim, Lily Napanangka and Peter Jupurrula, Elizabeth Newman, Ann Newmarch, Michelle Nikou, Miriam Stannage.

Curated by PICA Curator, Charlotte Hickson and Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art (CCWA) Curator Gemma Weston.

Image credits:

Agatha Gothe-Snape with The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, Trying to Find Comfort in an Uncomfortable Chair, installation views, 2019. Photos by Bo Wong. Courtesy Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA).

— Agatha Gothe-Snape with the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art

Perth Institute of Contemporary Art

27 July – 6 October 2019

With works and contributions from: Elise Blumann, Penny Bovell, Angela Brennan, Susanna Castleden, Penny Coss, Janet Dawson, Helen Eager, Rosalie Gascoigne, Helen Grace, Giles Hohnen, Narelle Jubelin, Eveline Kotai, Maria Kozic, Mei Swan Lim, Lily Napanangka and Peter Jupurrula, Elizabeth Newman, Ann Newmarch, Michelle Nikou, Miriam Stannage.

Curated by PICA Curator, Charlotte Hickson and Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art (CCWA) Curator Gemma Weston.

Image credits:

Agatha Gothe-Snape with The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, Trying to Find Comfort in an Uncomfortable Chair, installation views, 2019. Photos by Bo Wong. Courtesy Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA).