Suburbs

24 November 2019

Hayley Megan French in correspondence with Robert Wood

The Border Line

25 October 2019

Dear Robert,

I am currently a visiting artist with The Border Line where Alana Hunt has introduced me to your book Suburbanism. In this book, I feel I have found what I have been yearning to read for over a year now. It has been over this year also that I have felt an increasing connection to poetry, and literature, as an expression of place, and one that I feel a local identification with.

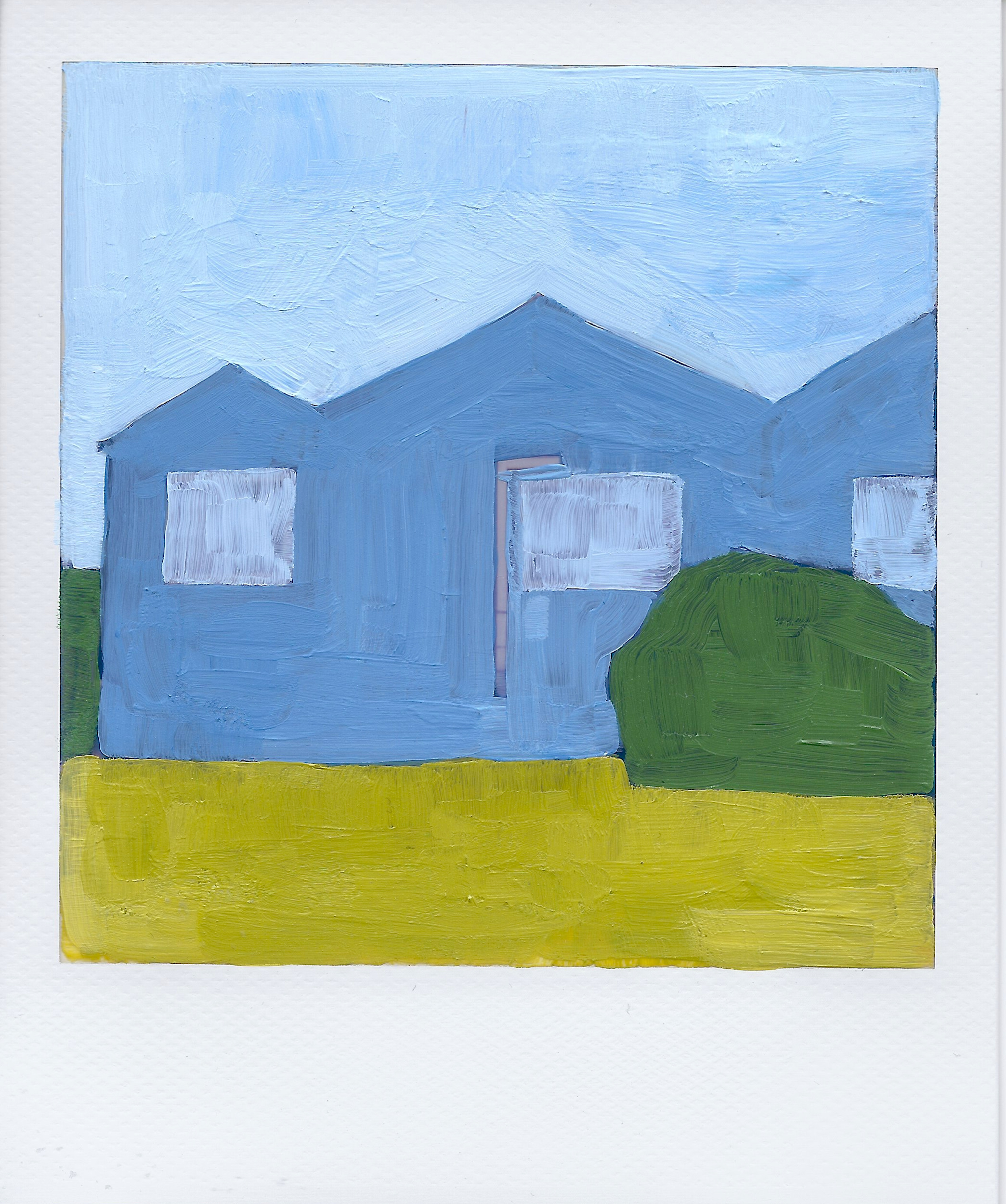

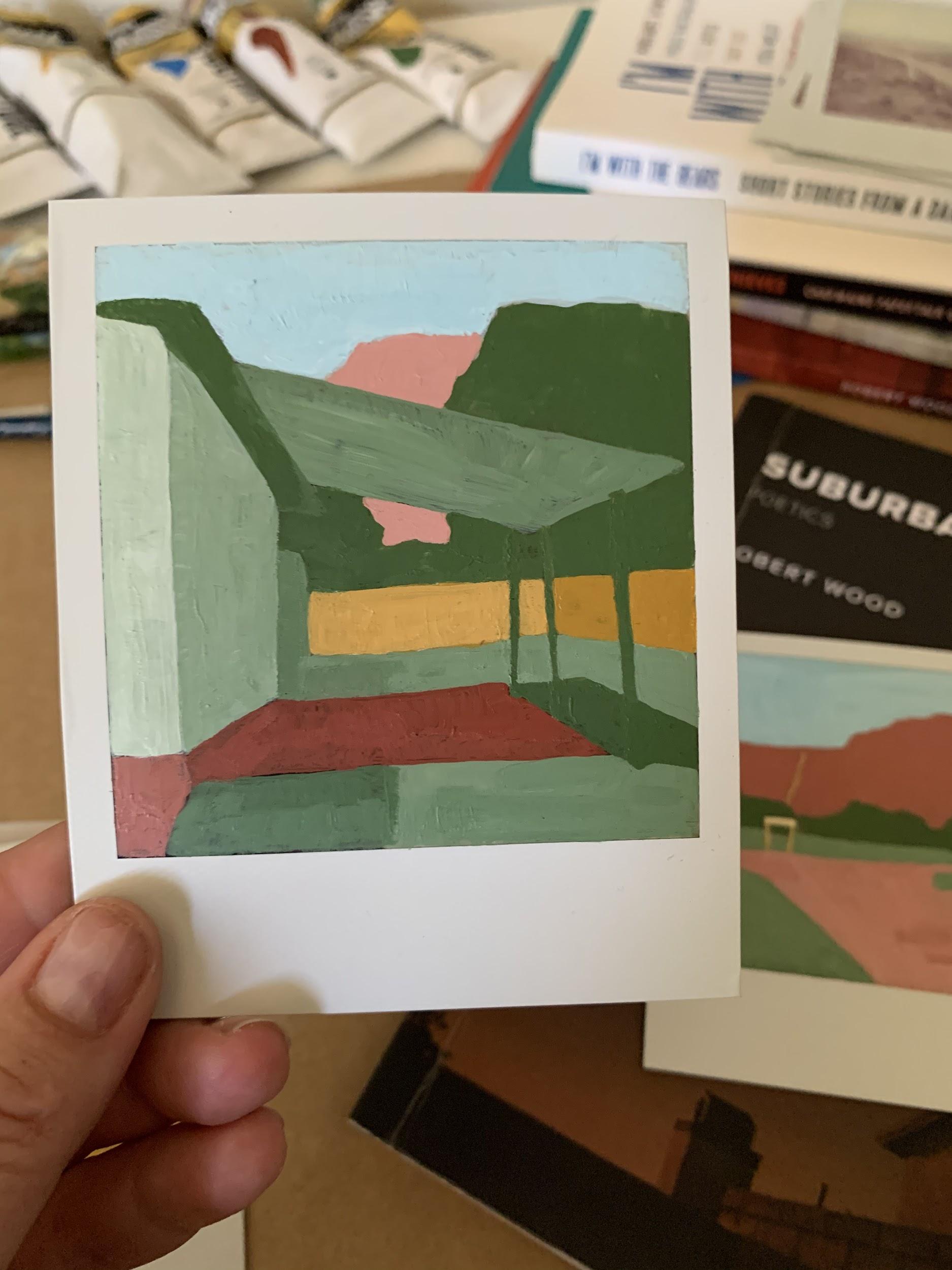

While I am here in Kununurra, I am reflecting on my current project which documents and interprets my experiences of living in Guildford, the unceded home of the Bidjigal Clan of the Darug Nation. Guildford is now a Western Sydney suburb home to the largest population of Arabic-speaking diaspora in Australia. I am marking, through painting, the signifiers that describe where and who I am: the colours, the yards, houses, signage and sounds. I walk down the street to buy bread from a family-run grocer. I fall asleep to Arabic gospel music from the church next door. I wake to the sound of my neighbours’ birds. These individual moments are part of the collective experience of my neighbourhood.

My understanding of contemporary landscape as place is informed by my research on the influence of Aboriginal art on how artists think about and make paintings in Australia. This influence is profound and widespread, contributing significantly to an understanding of both painting and landscape as a conceptual practice - one through which artists can consider the tensions of colonial and settler cultures. Land and belonging are increasingly understood in terms of the connections between landscape and power and modes of self-formation and identity.

It is in this context that I attempt to record my suburban experience - a way of thinking of landscape as suburbia, or more, landscape as place as identity (and the more I read your work) as the poetics of suburbanism. As painting.

I love this quote by author James Salter:

It’s in the little towns that one discovers a country, in the kind of knowledge that comes from small days and nights.1

In my own painterly record I am shifting between abstraction (contemplative) and figuration (story), and drawing on the presentness of painting in works such as On Kawara’s time and location pieces, Grace Robinya’s storytelling and the nostalgia of Idris Murphy’s landscapes. Colour has become an important part of this project in it’s connection to a particular place and time. Many of the homes in our neighbourhood are post-war fibro homes of pale blues and mint greens. It is hotter in the Cumberland Plain that the city, grass yellows in summer and at dusk the pinky-yellow light of the sunset penetrates our windows.

I have begun by taking polaroids, first in my backyard, and slowly, out in my neighbourhood. I paint over the polaroids because I want them to be more than photographs of this place, but narratives that can recall different and broader experiences. I paint over them to spend time with them. Your comment of the poem becoming a way to generate an intentionalised understanding of suburbia really resonated with me here.

I have lived in Western Sydney all my life, yet here in Guildford I am a newcomer, perhaps even an interloper. The dominant cultures of the area are not ones that I grew up in. However I do know that this is where I want to be. I hope that the diversity and distinctiveness of the Guildford suburbs (Old Guildford, Guildford, Guildford West), embodied by every house, every yard, in every business (except of course the multiple Aldi stores, which upon reflection also contribute to my sense of belonging - I shop at Aldi, because I live in Guildford), is somehow captured in my work. Or in the least gestures towards it.

I am also very aware that this area is changing, morphing into a suburb of new duplexes of contrasting building materials, of knock-down rebuilds. We may yet be the ‘inner-west’ of a rapidly growing Parramatta city-centre. Even as I contribute to this change — my partner and I building a small home and studio on a sub-divided block in Guildford recently released by Sydney Water — I hope it will retain the multiple identities that have been established and nurtured by families living here for the past 40 years, and will do better in acknowledging and celebrating those of the Darug people who lived here all those years prior to invasion.

I have been trying to write an artist statement for this body of work. However I am finding it very difficult to do so as I am much more interested in how it may sit in a wider context of artists working in Australia today, and how our works, made alongside one another in this time and place, can speak to a sense of identity, national and individual (and the importance of suburbia in this conversation). How our differences, more so than our similarities, can contribute to a new narrative of who we are, and better yet, who we want to be. How suburbia can be a story of relationships and connectedness, of how we live alongside one another, and are connected to a world outside of ourselves.

As I write to you, I am working in a very different suburb, an island suburb surrounded by the Kimberley Savannah. I want to spend more time thinking about what you have written of the intersection between decolonisation and the suburbs. But I will leave it here for now. Thank you for your words, and thank you for sharing them.

Warmly,

Hayley

︎

Wandi Wa Hayley,

I think of texts, be they paintings, photographs or poems, as having critical possibilities in them that can be discerned, called forth, embodied because of the work by artists, broadly meant to mean those attuned to making something from nothing. That might mean an uncovering, or a revelation, or even enlightenment. That might mean their opposite as well - a painting over.

From the start, it is important to see that these possibilities are multiple, especially in the contexts of nations, where so much depends on the attempted monopolisation of violence. The nation, in the nation's eyes, is not at war with itself precisely because they are the legitimate owners of guns, detention centres, prisons, all disseminated through laws, courts, police. I say that as a fact. I do not say that as a critic living parasitically by taking apart people's hard done work, or thinking I can reveal the true consciousness of another artist’s work; nor as an anarchist that would hope the state go away.

I say it as a suburbanist.

What might that mean? And why does it matter for your own projects, in Guildford or in Kununurra or anywhere else along the way? If nothing else it matters because you are not alone in a beautiful and traumatic world. Being a suburbanist partly means thinking about the re-organisation of space, of territory, of place; of seeing this continent and its countries as distinct from the nation. Here, our language matters, and we hear people in politics speak of ‘Australia’ meaning the state. That is tied up with land, especially because of terra nullius. The word ‘land’ is reserved somewhat for landscape, en plein air, and watercolours, the types of paintings that we know from galleries and post-cards. In English, ‘country’ comes more recently, and seems to be an attempt to translate ‘ngurra’ (Ngarluma) or ‘boodjar’ (Noongar) or other local expressions. The different words have different meanings and are said differently in different contexts. Perhaps they are all a kind of nature, and here, it means looking at the suburbs as a special category of place, not only as the accumulation of particular locations such as Wembley, Ernakallum, or Paterson.

Suburbs are islands in my mind, and, the sea might be the world.

But, what happens to our possibilities when we go deeper, when we try to find the aquifer once we see the river, to realise that this island is a continent made of thousands upon thousands of countries here? That is, I think, not only about place, not only about land and country, but about identity, about the suburbanist as a thinking subject. This is not only the suburban as the content of our artworks. This might be about the spirit of the maker once we realise that the materialist expression of that person depends in part on their lifestyle. We are conscious we dwell in territories we call suburbs, but we do not know how to label ourselves without recourse to something else - settler, communist, liberal, unionist, feminist, and everything else. We must acknowledge these imagined communities then, and, construct a practice of everyday living that depends on our place as a way to create identity. To be the suburbanist might be about making meaning when others only see reality as deracinated, boring, and dull; or that cannot find a way through the warring state that the colonial nation sustains. It responds then, in some respects, to the ugliness, makes art from detritus, sees that this periphery is not dependent on the metropole but can network itself laterally so that we sustain ourselves wherever we dwell.

And then, from that, from the identity and the lifestyle, it might be about the world historic, of how we matter. This is not as instrumentalised relevance in the marketplace of commodities and ideas, but in and of and for ourselves and each other - that the suburbs are a place that we represent with fidelity, that we paint on the continuum of abstraction to figuration; and, that the suburbanist is the artist who makes this known even as it can be found in the gospel singer and the bread baker. That we belong to othered postcodes, those beyond the art world alone, and, where we seek to know our neighbours as more than their cars, their flat pack furniture, and their private school uniforms. The sea, the world historic answers why this matters, it gives us a system of thought that is pliable, that can run alongside other possibilities from the same evidence. It can make its justice and its healing known. That is why we must retrofit, why we cannot turn away from trauma, why we persist in the face of concrete doubt and acid rain. We must acknowledge history then but not be defined by it. After the culture wars, don’t we need a philosophical understanding of our place in the world?

That means seeing art for what it can be and what it is now - your palimpsest that is post-national without a romantic return to an imagined past that never was, nor a modernist disavowal that we can never be made whole. This is a bridge among other things, but not constructed on the bones of others, nor made by the main roads department. It is a bridge of dreams alone where we learn to trust in our sense that the quotidian is the evidence before us of how we might go on.

Robert

︎

27 October 2019

Hi Robert,

It has been a pleasure to read your email over the past couple of days, laying beneath the ceiling fan. It is a beautiful sensory experience of the quotidian – the spinning, the humming, the breeze on my face.

There is a backyard yacht I have encountered on many early morning walks through Guildford. This image comes to me now as a visual of your descriptor of our suburbs as islands, the sea as the world. I often wonder how they move the yacht in and out of the yard.

The liminality of the suburbs is so visually striking here in Kununurra. The Borderline project exists in this space, being on both sides, and on the threshold, of suburbia and ‘the outback’, Miriwoong culture and settler cultures; past, present and future as a continuum that we are all implicit in. All the trauma of continuing colonisation you can see here, and you cannot deny. I am here in a beautiful home that Alana and her family have created, and have been lucky to see the homes they are building on her partners’ Mothers’ Country, on the borderline of WA and NT. There is so much love, and goodness here. So many fruit trees, and shared meals, and eggs from the neighbours’ chickens. So many artists telling, capturing, sharing important stories. I can’t help but romanticise.

Back home in Guildford, in Western Sydney, this visual liminality is so present in the cultures and inheritances of our migrant populations. There is an urgency by local artists to share the diversity and complexity of their diasporic experiences. There are artists, writers, poets, theatre-makers, musicians and all sorts of makers creating art in every suburb, as the ceiling fan turns. In and around Guildford I think of Marian Abboud, Justine Youssef, Linda Brescia, Khaled Sabsabi, Felicity Castagna, Arab Theatre Studio, Dance Makers Collective, Lost in Books, to name a small few. Their work questions what it means to live, work and tell stories on unceded land where many different languages are spoken. And I think, is driven by the imperative that the only way forward is to continue to do so, so that we can work out together what it might be to decolonise no matter what diaspora we are from2 - as you say. You have written that:

it is up to us to demonstrate that the aspirational expectation for a suburban style of life is compatible with a form of republican sovereignty that responds to calls for recognition, treaty, the republic, a bill of rights, and land restoration.3

I worry about how to do this, and that there is often a disconnect between my intention and the works I create. But as I write, and think on these two suburbs of Guildford and Kununurra, I wonder if we are already seeing here what this decolonising / unsettling might look like.

I believe art has the power to inspire us or remind us to live more consciously. To slow down and take in our everyday experiences, and at the same time acknowledge that there are infinite other everyday experiences. And that all of these can be good. I think this leads us to wanting to consciously participate in a future that is bigger than our own.

Making work in Guildford has brought my consciousness back from ‘out there’ to the very streets I walk and the suburb I choose to live in. I heed the call to expand my sphere of engagement with the world historical system that is beyond the national, one that sees a family resemblance between India, South Africa, the Caribbean, as well as the resistance to it.4

Warmly,

Hayley

︎

Kaya Hayley,

I think seeing colonisation as a world historical system also means seeing how important acts of resistance are when they negate it. It might be then to reflect on the quotidian, but to also see the evidence before us, including the fact that we are working towards something different. The fruit trees, the neighbour's eggs, the diaspora internal and external, all those things may be discursively framed as evidence for 'the colonial' or post-colonial or decolonial, but they are also other things in and of themselves. And so, our critical possibilities are multiple.

I am not a theorist of colonial experiences - there are lots of people for that - nor do I think it is space I can take up in relation to this nation. I am too utopian to simply want to unsettle. Besides, that seems like an impractical response that cannot be supported by action. And, as far as I think, know and feel, my family decolonised in India in 1947. If I think for a moment too, of Singapore mattering as a place in my story, then that place also decolonised in 1965. I am not able to speak to the nation, nor to colonisation, not here when that here is smaller than 'the world'. I do think though, that if people in ‘Australia’ want to decolonise they should look to traditional owners and to places further along this path, re-route their networks in regard to those who are liberated from these particular shackles. There is work that has been done in the 1946 Pilbara Strike, and the same era in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean. I just don't think it is up to white settlers to lead this, so it is good to move over, to seek one's own enlightenment by making a community that matters. Your actions can tend towards solidarity, something that pre-dates and matters beyond the ally.

My concerns are different. I acknowledge colonialism but am not defined by it.

What I will say though is that if terra nullius is the philosophical principle behind Australia's inflection on the colonial, we might also want to talk about parens patriae as an analogue for suburbanism as a historical materialist phenomena. Of course, the suburbs are a place and a space, and hence, land. People here are obsessed with land - acknowledgement of country, property prices, land rights, crown land, city expansion, ecological destruction, national parks, water usage - and well they should be. They can talk about that. I want to talk about other things. Philosophically minded as my task is, and, as ambivalent as I am about the suburbs, we need to talk more about people, which is not the same as identity, nor of finding origins and categories, not even of labour. And so, I would encourage you to think about parens patriae, which is what underpins 'wards of state'. It is the nation as parent. This is land as person, person as land.

If I were to talk about colonialism today, parens patriae would be the principle to uncover precisely because I do not hear people talking about it, even as it connects us to events and individuals beyond these shores. Removal of children, denial of citizenship, deaths in custody. This happens to people, to sovereign individuals. It is a violence done where it matters - to the body itself. Parens patriae is something theorists, intellectuals, artists do not think about, but it continues to the present day.

It also means we need to think of how people change, of how we move through the world like suburbanists might in order to heal our very selves as a way to restore country and each other. This is how we respond to PTSD, lock ups, our own confinement. It is about something else that can be taken with you. It connects us to slavery, to indenture, to convict transport. To be a ward of the state does not rely on land, but parens patriae is just as important as terra nullius for everyday life, just as mass incarceration matters as much as land rights. It is also something that is about power that depends on different groups rather than reifying notions of identities we are attached to.

I was visiting Ngarluma family members in jail the other month, down here, in a suburb that borders the rural called Jarrahdale. The prison is a prison farm and they supply food to all the other prisons in Western Australia. It is nice as far as prisons go. We drank watery cordial in plastic cups, and, all the prisoners sat around in green uniforms. We chatted and just made sense of what was going on. It is not fun to be inside these total institutions, not mental hospitals, not prisons, not fun to be under parens patriae, to be a ward of the state. If you have been, you will know it is not freedom.

What then is it to see the outside world as a type of liberation if one has been inside? It depends then on the relative experience, on where one has been that is at war, to read subtle signs, to pick up on things, to persist and go on. Always good to get off the island, but when one is a body, always nice to have out of body experiences and inside of body ones too; to dream and travel far away in the sleeping state. To be a ward of the state, to live with parens patriae, depends a lot on seeing beyond the nature.

I imagine they move the boat with a big car, but someone uses their hands to hitch it to a trailer. People are more often complex from afar.

Robbie

︎

29 October 2019

Hi Robbie,

It has been such a joy to be introduced to your work, and yourself over email while I am here in Kununurra. It has, in turn, been affirming and challenging to read your responses. I have not heard before of parens patria or thought of this doctrine as an analogue to suburbanism. My thinking and reading world has indeed been importantly expanded. I have written before of the body as landscape, and the way the body holds our personal, social, political histories. Of how to translate our embodied experiences, between the collective and the individual body, to have resonance with a context other than our own. Your email has me revisiting these ideas, in the context of suburbanism and parens patria, in a way that I hadn’t previously connected. Alana and I have just now been discussing state control over our bodies, over the way we can exist in space and place, which we do see so clearly in suburbia. I do often come back to the writing of cultural activist Justin O’Connor of the great questions of ultimate value: of how we can live together, and what the quality of our collective experience should be (Platform Paper 47).

I am also thinking a lot of your conclusive remarks in the essay Renewing Localism,5 of the need to retrain our senses, to better look, see, listen, learn and poetically engage with the world (and people and difference) from where we stand. My current process of photographing and painting-over is helping me to better see, and reflect on more intuitive actions and responses in this space. I will continue to engage with all of these questions, the last (in your essay) being: how can we see our suburbs differently by re-reading Robin Boyd and Howard Arkley in light of Rover Thomas and Reko Rennie?

I would love to hear if you have any suggested reading for me as I continue? I have just recently ordered Kate McMillan’s Contemporary Art and Unforgetting in Colonial Landscapes; Islands of Empire. I am looking forward to getting into it when I return home.

Thanks again for your thoughts, time and generosity.

Warmly,

Hayley

︎

Vanakkam Hayley,

It has been wonderful to write to you on this, and, I am glad this dialogue has just started. The last image you have sent through is of a sunset. In Ngarluma language, it is 'tarruru', which means 'peace of mind', 'evening glow' and 'dusk' all at once. In my language of Malayalam, we say sūryāstamayaṁ. In Suburbanism, I might say twightlitten, but that is adjacent. Here then, it is not about a transposition into English from Ngarluma or Malayalam as though we mined it for what is useful to us. It is to learn, in good faith, about what makes sense in responding to landscapes, to collaborate, to make a world when they are telling us we cannot.

In that way, in so many ways, the suburbs do not make sense. If they are left to suburbanites, this is about the exploitation of the material base without a dialectical care in the world, not for the displaced ecologies or the lack of good social relations that culture makes. That would let suburbanites take what they want as the seas rise and the people are oppressed. And yet, we cannot turn away from suburbia, we cannot refuse this as a post-structural system, not as the banal occupation of land, not as a place where people live. This is, like you say, the body in space. It simply gives us work to do. It is meaningful in that way, a lifestyle to make conscious, to articulate, and, as a way that responds to relations that acknowledges race but isn’t defined by it, acknowledges class but isn’t defined by it, that acknowledges gender but isn't defined by it. There is no master key to identity, no singularity to explain it all; but in lifestyle we can understand the bundles of relations that go into our place and our bodies as well. From bridges to dams to prisons, and on and on to hearts, lungs, kidneys, spleens, stomachs.

That all might be a way of saying, theory and language might be best discarded after we have crossed that bridge, like the ladder before us, and the owl before that. The bridge can be the back, our very spines that we always take with us; but it might also be made from bamboo or recycled plastics or paintings from old masters. Maybe photographs, negative images.

I have written Suburbanism out of my body, and now I live in the city, in an apartment of modern proportions, even as there are chickens and fruit trees and curry leaves that are shared by all our building’s dwellers. What to read then must include a way of seeing the world, and, the text might simply be what you return to and call home. The language to make sense of might simply be your own.

As for lists, I like Emily Wilson's Odyssey, John Minford's Tao Te Ching, Ranjit Hoskote's I, Lalla. That might be the bedrock before we come to Helen Lynd's Middletown, Tom Sugrue's New Suburban History, DJ Waldie's Holy Land, which brings us closer to now. And then, of course, there is Tarruru by von Brandenstein and Thomas, those poems of daily life that bring us full circle, to another sunset on another day.

To connect all the dots on the way, to make sense of a system around us, means assembling the evidence before us, means bringing to consciousness what we take for granted, means regarding the suburbs with something that approaches sanity. That matters for the daily actions we take towards sovereignty, in our countries and in our bodies; of how we hold space, and keep the law open, waiting as always for another generation to take our place. I am from the suburbs, but not quite of them, and in letting go now, this allows one to pick up something worthwhile in the process of going deeper into the soul as it matters to a new world.

Travel safe,

Robbie

In October 2019, Hayley Megan French was the innagural visiting artist with The Border Line, an experimental cultural initiative on Miriwoong country established by Alana Hunt.

Also in October 2019, Robert Wood published Suburbanism: Poetics with Australian Scolarly Publishing.

All images courtesy of Hayley Megan French.

Also in October 2019, Robert Wood published Suburbanism: Poetics with Australian Scolarly Publishing.

All images courtesy of Hayley Megan French.

1James Salter, 1967, A Sport and a Pastime, Doubleday: New York.

2, 3 & 4Robert Wood, Suburbanism: Poetics, Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Press, 2019.

5Robert Wood, History and the Poet: Essays on Australian Poetry, Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Press, 2017.

2, 3 & 4Robert Wood, Suburbanism: Poetics, Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Press, 2019.

5Robert Wood, History and the Poet: Essays on Australian Poetry, Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Press, 2017.