Suburban displacement, suburban estrangement: where are the people?

31 May 2020

Correspondence between Christina Chau and Kelly Fliedner in response to Ian Strange’s Suburban Interventions 2008 – 2020

John Curtin Gallery, Perth Festival

Dear Kelly and Hetty,

After going to Ian Strange’s Suburban Interventions I have a lot of questions for Ian and the answers can’t be found in the works. I’m familiar with Ian’s practice—we met a few times in 2013 (or 2014?) to talk about his work. He told me that one of the main influences or guides for his practice was a book called Australian Ugliness by Robin Boyd (1960). He leant it to me and I never gave it back.

The exhibition is very slick, the photographs and films are produced with a lot of care, and he’s made use of the main gallery space really well, which is hard to do with a small number of works. I imagine that there were teams of people, a lot of resources, money, bureaucracy and project management that has gone into accomplishing each work. Ian must have a great team, and I am assuming is also a highly organised person who is able to articulate and execute his vision. Being able to work internationally and talk to multiple stakeholders, deal with OHS, council regulations, permits etc., is the kind of headache that I don’t have the grunt for. And yet while it’s interesting to view his works together and see how he’s been crafting, refining, and restaging his ideas all over the world, when I walked out of John Curtin Gallery I felt disheartened, really sad.

Full disclosure, I was going to feel sad anyway: The day I went to the exhibition happened to be both the anniversary of my Dad’s death (he committed suicide in his house) and the day that I paid our deposit for the house we’re buying (settlement is today).

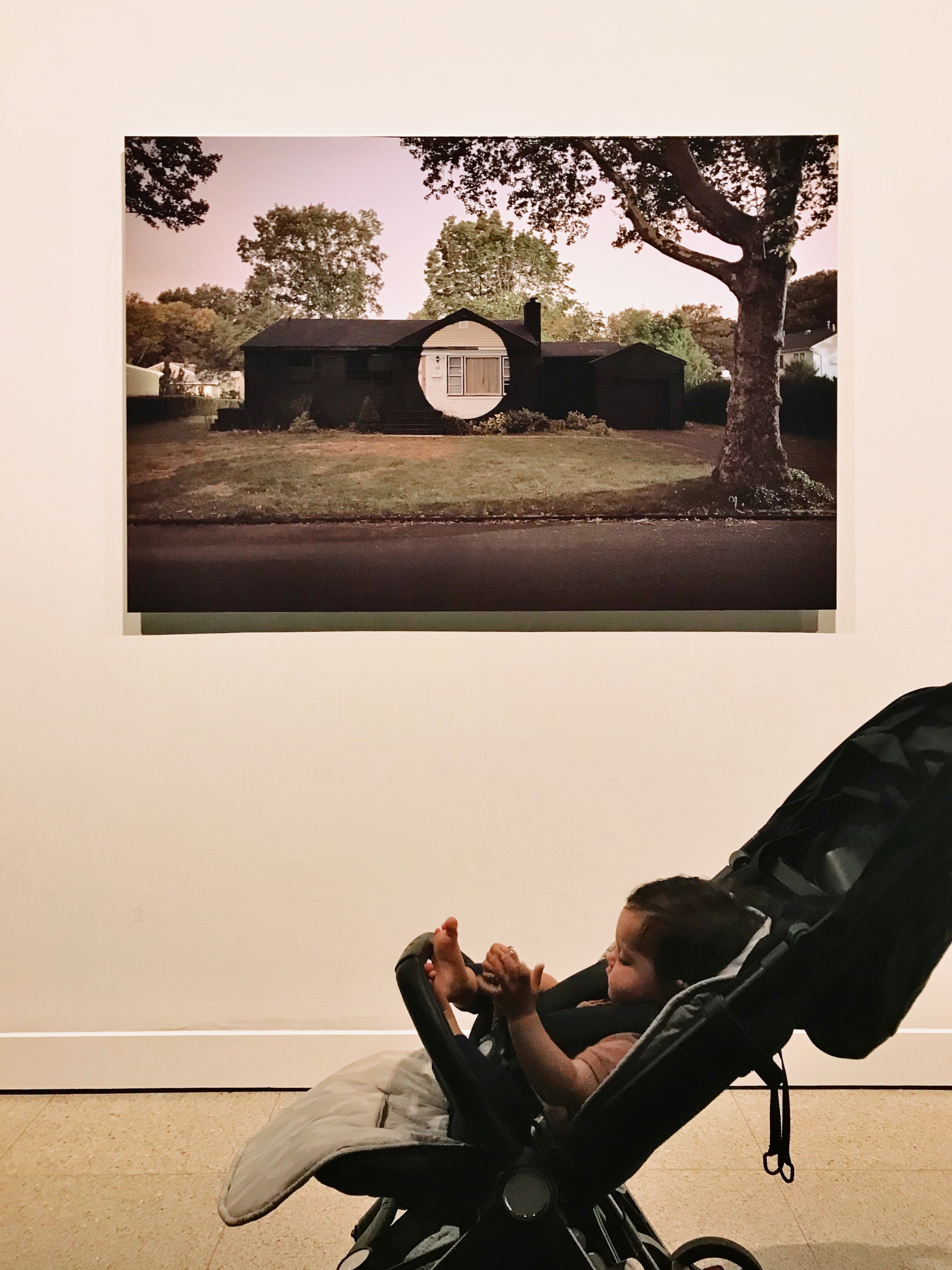

Ian’s works are ‘suburban interventions’ where he comes in, reworks an abandoned or soon to be demolished house. But the term ‘intervention’ usually brings up connotations of inserting oneself into a situation for long term progress—to intervene and break or interrupt a flow or course, and steer it towards a better situation. Ian certainly does insert himself, but we know that most of these houses are demolished (as planned). So his intervention is temporary, like a pop up bar in a park, or a hiatus before the area is redeveloped.

And when I look at each house I’m flooded with questions: what did these houses look like before? Who lived there? What happened there? How do people feel if/when they see their family home redressed temporarily before it’s demolished? It’s also really difficult to look at the exhibition and not think about the recent bushfires all over Australia this summer, of neoliberal economic instability, and persistent colonial narratives of displacement and paradoxical re-settlement.1 It’s not about the presence of place, but the absence of people.

This is one of the reasons why I left the exhibition feeling so sad. These were peoples’ homes—where they grew up, or gave birth, united or parted ways. In these homes there were probably long nights, celebrations, feelings of angst, mourning and joy, but there isn’t any hint of time and relationships in Ian’s interventions—instead one house is approached like the next, and the next and the next.

What really surprised me going to the exhibition and seeing these specific works together in one gallery was how similar the houses appeared—or were made to appear. Even though Ian has travelled to the USA, New Zealand, Australia, and beyond, and records a mixture of suburban architectural styles, he’s very effective in wrapping each house with his own aesthetic. Is this a form of artistic branding? And if so, this global approach to art making disregards localised contemporary concerns about land, climate crisis, belonging, and heritage.

While Ian, like Robin Boyd, is interested in repetition, invisibility, monotony and the mundane aspects of suburbia, I feel like they’re easy connotations to make about suburbia in general, when looking from the outside, which Ian inevitably must do as he travels from country to country. He’s not making works about his suburban upbringing, or his family home – he’s visiting specific suburbs as an outsider, intervening, and documenting, and then leaving. He inevitably glosses over the nuances, the special sentimental actions associated with personalising a house, or garden, makes the uniqueness monotonous.

Given his tendency to intervene as an outsider, I wonder if Ian feels sentimental about his family home, whether he’s lost or moved from a home and deeply mourned it, of if he’s lost a family member in a home, or buried a pet in the garden. I’m not wondering these things and deep down saying “I bet he hasn’t”—I’m genuinely wondering, and then thinking about how he feels any interest or longing to know more about the people who lived in the houses that he’s intervening with. Why doesn’t he let any nuances about place creep in? If not his own, what about the houses and memories that he paints over?

And because Ian dresses the outside of the house, with little indication of who was there beforehand, the exhibition feels like an illustration of displacement, or maybe, the consequences of displacement: a disconnection from history, identity, sense of place and community. It makes the curatorial decision to have Sandra Hill’s exhibition Mia Kurrum Maun (Far from Home) next to Suburban Interventions really fascinating. Hill’s work is also an illustration of alienation, disconnection from home and family—but unlike Strange, Hill’s displacement is through force. And so while Hill is acutely aware of the social consequences of disconnection from home, she uses her work as a way of thinking through individual and collective alienation. Having her work next to Ian’s, really hits hard how dangerous and blind it is to think of suburbia as a predominantly white experience (as expressed by Boyd, and I’m assuming here also); how displacement and historical amnesia are damaging for everyone; and how global artistic branding rarely listens to (or makes room for) the nuances and intricacies of place.

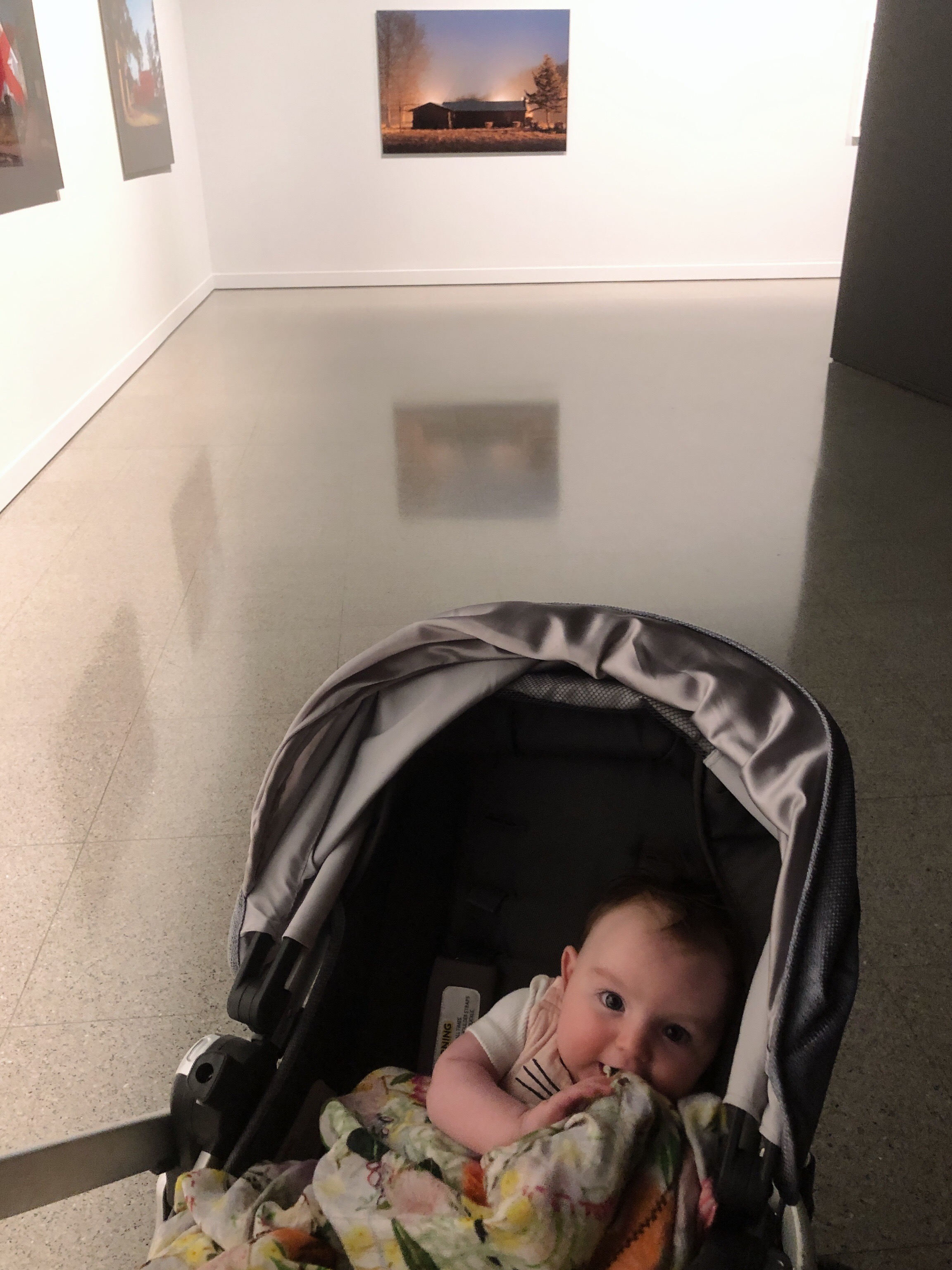

I don’t mean to be so hard on Ian—as I said before, I wasn’t in a great place to begin with, and Aki started to scream in the gallery.

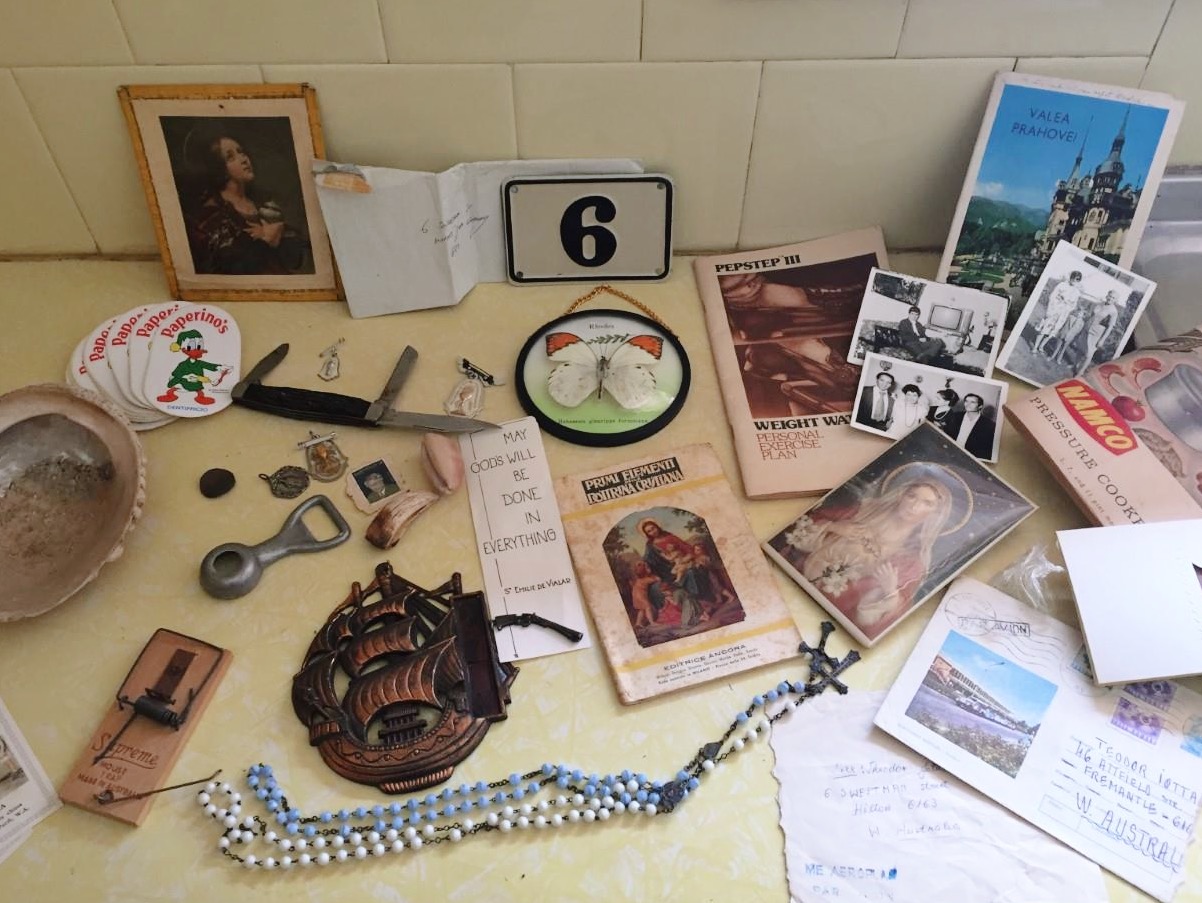

I’ve been writing this letter on and off for three weeks now. I’ve only got time to write when Aki is napping, and after I’ve done my work. Over these weeks we’ve bought our first family home and I’m baffled that we’ve done it, and that Aki will grow up in this place. We bought a big kitchenette and Dan got the work truck and craned it into the shed. When he opened up the shed he noticed that the owners left their family kitchenette there and it was full of family memorabilia: rosary beads, photographs, coasters, abalone shells, and pressed butterfly hangings. The items that make a home, and a life. It's a beautiful collection – we won’t change a thing.

Love,

Christina and Aki

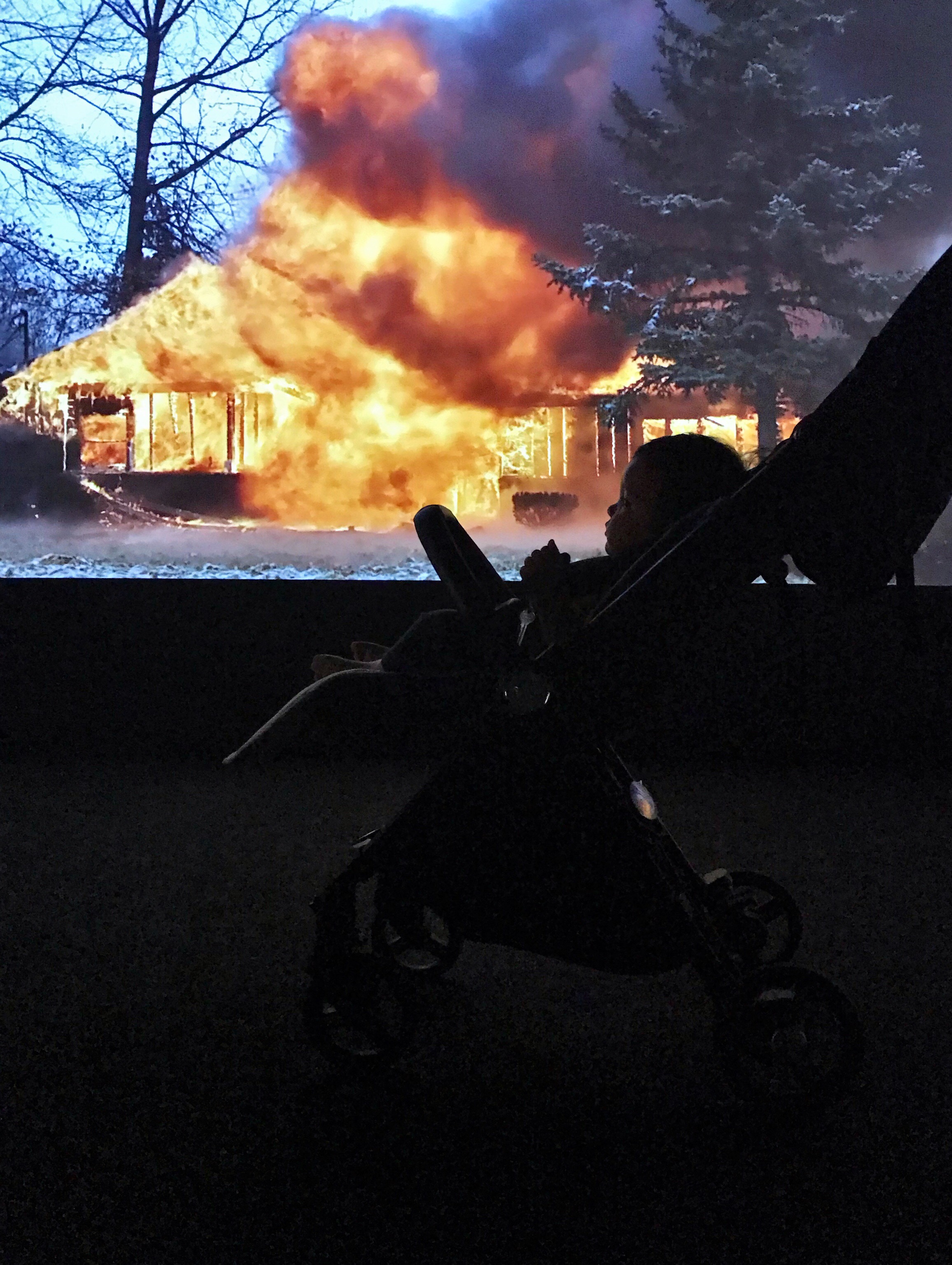

1A large part of the exhibition is taken up by a central video work as part of the Suburban series (2011-2013) in which a house is filmed fully engulfed in flames. Perhaps this work in particular resonates differently from Ian’s original intentions because of the recent bushfires across Australia. This Black Summer resulted in an estimated 186,000 square kilometres of burnt forest, bush and farmland, killed at least 34 people and around one billion animals, and destroyed 5,900 buildings (including 2,779 homes). The burning home becomes a real world register of tragedy that unfortunately these works, and the provided discursive information from John Curtin Gallery were surprisingly and perhaps unforgivably tone def toward.

After going to Ian Strange’s Suburban Interventions I have a lot of questions for Ian and the answers can’t be found in the works. I’m familiar with Ian’s practice—we met a few times in 2013 (or 2014?) to talk about his work. He told me that one of the main influences or guides for his practice was a book called Australian Ugliness by Robin Boyd (1960). He leant it to me and I never gave it back.

The exhibition is very slick, the photographs and films are produced with a lot of care, and he’s made use of the main gallery space really well, which is hard to do with a small number of works. I imagine that there were teams of people, a lot of resources, money, bureaucracy and project management that has gone into accomplishing each work. Ian must have a great team, and I am assuming is also a highly organised person who is able to articulate and execute his vision. Being able to work internationally and talk to multiple stakeholders, deal with OHS, council regulations, permits etc., is the kind of headache that I don’t have the grunt for. And yet while it’s interesting to view his works together and see how he’s been crafting, refining, and restaging his ideas all over the world, when I walked out of John Curtin Gallery I felt disheartened, really sad.

Full disclosure, I was going to feel sad anyway: The day I went to the exhibition happened to be both the anniversary of my Dad’s death (he committed suicide in his house) and the day that I paid our deposit for the house we’re buying (settlement is today).

Ian’s works are ‘suburban interventions’ where he comes in, reworks an abandoned or soon to be demolished house. But the term ‘intervention’ usually brings up connotations of inserting oneself into a situation for long term progress—to intervene and break or interrupt a flow or course, and steer it towards a better situation. Ian certainly does insert himself, but we know that most of these houses are demolished (as planned). So his intervention is temporary, like a pop up bar in a park, or a hiatus before the area is redeveloped.

And when I look at each house I’m flooded with questions: what did these houses look like before? Who lived there? What happened there? How do people feel if/when they see their family home redressed temporarily before it’s demolished? It’s also really difficult to look at the exhibition and not think about the recent bushfires all over Australia this summer, of neoliberal economic instability, and persistent colonial narratives of displacement and paradoxical re-settlement.1 It’s not about the presence of place, but the absence of people.

This is one of the reasons why I left the exhibition feeling so sad. These were peoples’ homes—where they grew up, or gave birth, united or parted ways. In these homes there were probably long nights, celebrations, feelings of angst, mourning and joy, but there isn’t any hint of time and relationships in Ian’s interventions—instead one house is approached like the next, and the next and the next.

What really surprised me going to the exhibition and seeing these specific works together in one gallery was how similar the houses appeared—or were made to appear. Even though Ian has travelled to the USA, New Zealand, Australia, and beyond, and records a mixture of suburban architectural styles, he’s very effective in wrapping each house with his own aesthetic. Is this a form of artistic branding? And if so, this global approach to art making disregards localised contemporary concerns about land, climate crisis, belonging, and heritage.

While Ian, like Robin Boyd, is interested in repetition, invisibility, monotony and the mundane aspects of suburbia, I feel like they’re easy connotations to make about suburbia in general, when looking from the outside, which Ian inevitably must do as he travels from country to country. He’s not making works about his suburban upbringing, or his family home – he’s visiting specific suburbs as an outsider, intervening, and documenting, and then leaving. He inevitably glosses over the nuances, the special sentimental actions associated with personalising a house, or garden, makes the uniqueness monotonous.

Given his tendency to intervene as an outsider, I wonder if Ian feels sentimental about his family home, whether he’s lost or moved from a home and deeply mourned it, of if he’s lost a family member in a home, or buried a pet in the garden. I’m not wondering these things and deep down saying “I bet he hasn’t”—I’m genuinely wondering, and then thinking about how he feels any interest or longing to know more about the people who lived in the houses that he’s intervening with. Why doesn’t he let any nuances about place creep in? If not his own, what about the houses and memories that he paints over?

And because Ian dresses the outside of the house, with little indication of who was there beforehand, the exhibition feels like an illustration of displacement, or maybe, the consequences of displacement: a disconnection from history, identity, sense of place and community. It makes the curatorial decision to have Sandra Hill’s exhibition Mia Kurrum Maun (Far from Home) next to Suburban Interventions really fascinating. Hill’s work is also an illustration of alienation, disconnection from home and family—but unlike Strange, Hill’s displacement is through force. And so while Hill is acutely aware of the social consequences of disconnection from home, she uses her work as a way of thinking through individual and collective alienation. Having her work next to Ian’s, really hits hard how dangerous and blind it is to think of suburbia as a predominantly white experience (as expressed by Boyd, and I’m assuming here also); how displacement and historical amnesia are damaging for everyone; and how global artistic branding rarely listens to (or makes room for) the nuances and intricacies of place.

I don’t mean to be so hard on Ian—as I said before, I wasn’t in a great place to begin with, and Aki started to scream in the gallery.

I’ve been writing this letter on and off for three weeks now. I’ve only got time to write when Aki is napping, and after I’ve done my work. Over these weeks we’ve bought our first family home and I’m baffled that we’ve done it, and that Aki will grow up in this place. We bought a big kitchenette and Dan got the work truck and craned it into the shed. When he opened up the shed he noticed that the owners left their family kitchenette there and it was full of family memorabilia: rosary beads, photographs, coasters, abalone shells, and pressed butterfly hangings. The items that make a home, and a life. It's a beautiful collection – we won’t change a thing.

Love,

Christina and Aki

1A large part of the exhibition is taken up by a central video work as part of the Suburban series (2011-2013) in which a house is filmed fully engulfed in flames. Perhaps this work in particular resonates differently from Ian’s original intentions because of the recent bushfires across Australia. This Black Summer resulted in an estimated 186,000 square kilometres of burnt forest, bush and farmland, killed at least 34 people and around one billion animals, and destroyed 5,900 buildings (including 2,779 homes). The burning home becomes a real world register of tragedy that unfortunately these works, and the provided discursive information from John Curtin Gallery were surprisingly and perhaps unforgivably tone def toward.

Dear Christina and Aki,

It is almost a year to the day that we bought and settled on our little apartment in West Perth. When we renovated I found this damaged kodak photo behind the old kitchen cabinets. A father and his daughter at a ski resort, skis in hand, clad in colourful 80s nylon, surrounded by white. I wonder who they are and where they are and if they liked living in our home as much as we do. We keep the photo on our fridge.

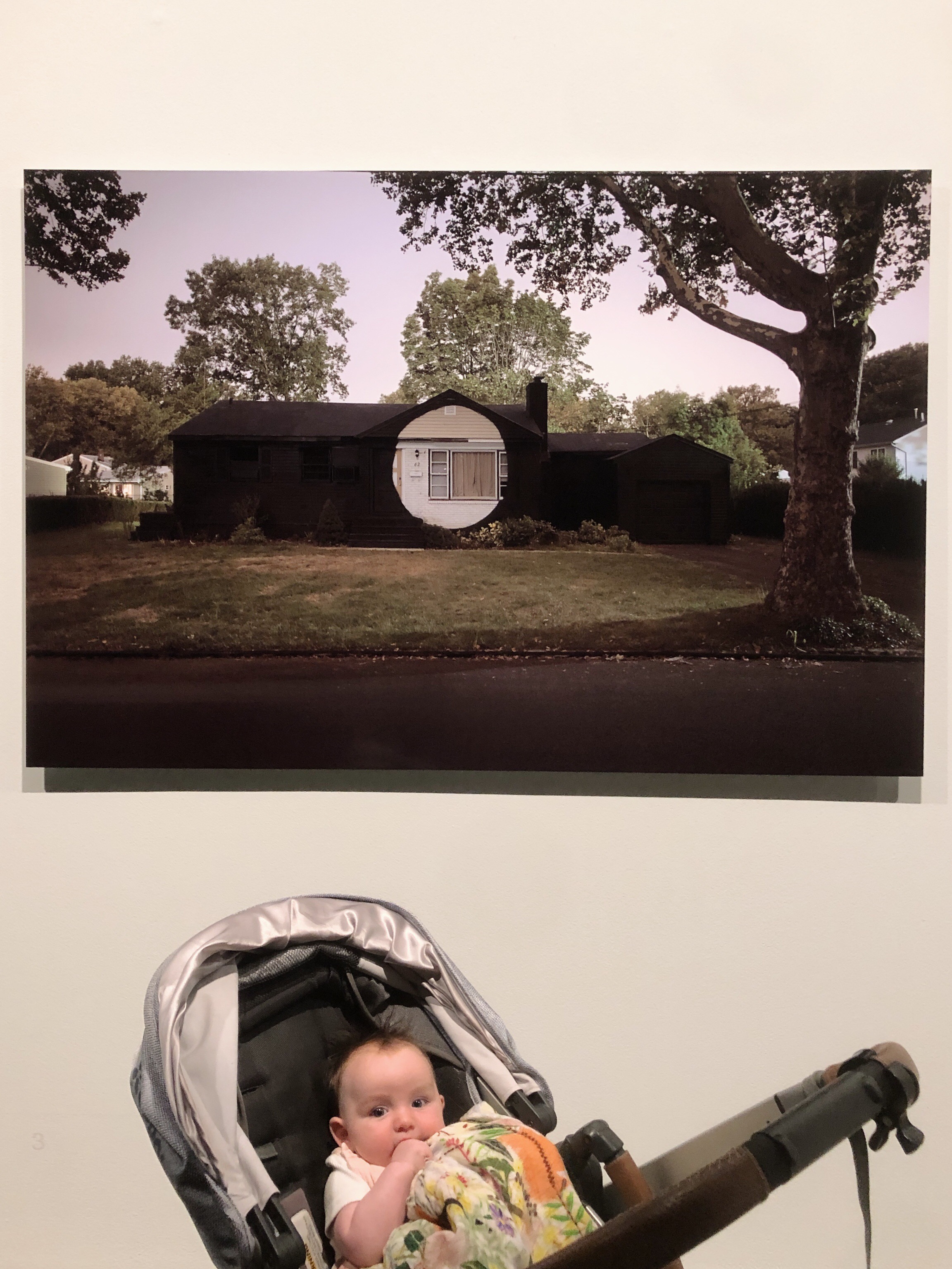

From West Perth, Hetty and I drove to John Curtin Gallery. She cried the whole way there and the whole way home. It was one of those ridiculously hot O week days and campus was filled with excited, sweaty, doughy-faced students. Instead of being in the air-conditioned hall of John Curtin, they stood uncomfortably under whatever piece of shade they could find. The gallery was empty. Hetty was wearing the dusty pink rabbit onesie you and Aki gave her 🥰.

It’s interesting that Ian gave you Robyn Boyd as a key reference for his work. I would never think of Boyd while looking at it but I know his work, and in particular that book from my undergraduate studies in Melbourne. The tone of Ian’s photos and videos are too gothic, too cinematic to evoke the humdrum mundane comedy of Boyd. They are filmic and sinister and the intensity of the houses are dramatised at every opportunity. Boyd is fundamentally ambivalent about the boredom of suburbia, whereas Ian seems to be enamoured with the aesthetic possibilities of the dark drama of suburbia, more Animal Kingdom than The Castle, more Snowtown than Kath and Kim, more Lantana than Neighbours. There is saturation but no playfulness, a negation of Howard Arkley. Although a critic, Boyd offered a precise appreciation for the ‘featurist’ veneer of the Australian suburb. Australian Ugliness is cutting but also filled with a larrikin affection for the idiosyncratic, ordinary, Australian suburban aesthetic from his own era. It is of its time, an observation of the specifically local, that could be national. It has fun, it rollicks, whereas Ian’s work is so incredibly earnest, so serious in tone. I don’t see any of this affection or evocation of the local. His work, as you say, is a series of flattened realities… a picture of sameness. Cool and detached.

The political register is somehow constant too, like samey. When we walked around the exhibition space what is clear is that his understanding of the ‘suburb’ is the single occupancy stand alone nuclear family dwelling from the post-war period. It is not necessarily the space between city and county, not a liminality that can then become material, but a concrete thing. Ian does not register suburbia as a contemporary condition, rather it is a past phenomena. His practice is historical in a weird way, not new developments, not malls or subdivisions, but abandonment. Maybe ultimately, it is conservative, interested in holding onto the dying, where he goes to white settler countries (USA, New Zealand, Australia) now marked for demolition. They become documents of the white settler fantasy of suburbia unable to reconcile the banal occupation of place that is colonial.

You’re right, it’s weird how there are no people. There is nothing domestic about these scenes. I see your point about the works being about displacement, and I would offer a related concept too: estrangement. There is an estrangement of the domestic that clothes the intimate with the monumental. It makes these quotidian and mundane things which are quite personal, quite small, quite specific into removed objects that are aesthetically smooth. I agree with you, it’s a type of flattening that objectifies people’s care for spaces. The works intervene rather than remove. They make it strange but without love, no matter how beautiful. And like you say, the juxtaposition of Sandra Hill’s intelligent, funny, heartbreaking works—many riffing on themes of the domestic and suburban themselves—in the foyer before you enter Suburban Interventions is not a favorable one for Ian. In the gallery thoroughfare, next to books for sale and behind large indifferent ‘PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH THE ARTWORKS’ bollards, they seemed like an afterthought to the main show in the big rooms next door, a rote learned Acknowledgment of Country. Wouldn’t it have been great if the circumstances—the spaces and resources given—were flipped?

As we drove home past figs and concrete swans, past lemon trees and dry grass ovals—while Hetty screamed—I thought of all these things. It seemed to me that what makes the suburbs a place of love is the people and the things they bring. The things they leave behind too like rosary beads or photographs or the shells they collect on the beach, learning how to be in new places and old places. Full, not empty. Keeping the ground open and hopeful.

Sending so much love from our little home to yours, from West Perth to East Fremantle, Noongar country always,

Kelly and Hetty

It is almost a year to the day that we bought and settled on our little apartment in West Perth. When we renovated I found this damaged kodak photo behind the old kitchen cabinets. A father and his daughter at a ski resort, skis in hand, clad in colourful 80s nylon, surrounded by white. I wonder who they are and where they are and if they liked living in our home as much as we do. We keep the photo on our fridge.

From West Perth, Hetty and I drove to John Curtin Gallery. She cried the whole way there and the whole way home. It was one of those ridiculously hot O week days and campus was filled with excited, sweaty, doughy-faced students. Instead of being in the air-conditioned hall of John Curtin, they stood uncomfortably under whatever piece of shade they could find. The gallery was empty. Hetty was wearing the dusty pink rabbit onesie you and Aki gave her 🥰.

It’s interesting that Ian gave you Robyn Boyd as a key reference for his work. I would never think of Boyd while looking at it but I know his work, and in particular that book from my undergraduate studies in Melbourne. The tone of Ian’s photos and videos are too gothic, too cinematic to evoke the humdrum mundane comedy of Boyd. They are filmic and sinister and the intensity of the houses are dramatised at every opportunity. Boyd is fundamentally ambivalent about the boredom of suburbia, whereas Ian seems to be enamoured with the aesthetic possibilities of the dark drama of suburbia, more Animal Kingdom than The Castle, more Snowtown than Kath and Kim, more Lantana than Neighbours. There is saturation but no playfulness, a negation of Howard Arkley. Although a critic, Boyd offered a precise appreciation for the ‘featurist’ veneer of the Australian suburb. Australian Ugliness is cutting but also filled with a larrikin affection for the idiosyncratic, ordinary, Australian suburban aesthetic from his own era. It is of its time, an observation of the specifically local, that could be national. It has fun, it rollicks, whereas Ian’s work is so incredibly earnest, so serious in tone. I don’t see any of this affection or evocation of the local. His work, as you say, is a series of flattened realities… a picture of sameness. Cool and detached.

The political register is somehow constant too, like samey. When we walked around the exhibition space what is clear is that his understanding of the ‘suburb’ is the single occupancy stand alone nuclear family dwelling from the post-war period. It is not necessarily the space between city and county, not a liminality that can then become material, but a concrete thing. Ian does not register suburbia as a contemporary condition, rather it is a past phenomena. His practice is historical in a weird way, not new developments, not malls or subdivisions, but abandonment. Maybe ultimately, it is conservative, interested in holding onto the dying, where he goes to white settler countries (USA, New Zealand, Australia) now marked for demolition. They become documents of the white settler fantasy of suburbia unable to reconcile the banal occupation of place that is colonial.

You’re right, it’s weird how there are no people. There is nothing domestic about these scenes. I see your point about the works being about displacement, and I would offer a related concept too: estrangement. There is an estrangement of the domestic that clothes the intimate with the monumental. It makes these quotidian and mundane things which are quite personal, quite small, quite specific into removed objects that are aesthetically smooth. I agree with you, it’s a type of flattening that objectifies people’s care for spaces. The works intervene rather than remove. They make it strange but without love, no matter how beautiful. And like you say, the juxtaposition of Sandra Hill’s intelligent, funny, heartbreaking works—many riffing on themes of the domestic and suburban themselves—in the foyer before you enter Suburban Interventions is not a favorable one for Ian. In the gallery thoroughfare, next to books for sale and behind large indifferent ‘PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH THE ARTWORKS’ bollards, they seemed like an afterthought to the main show in the big rooms next door, a rote learned Acknowledgment of Country. Wouldn’t it have been great if the circumstances—the spaces and resources given—were flipped?

As we drove home past figs and concrete swans, past lemon trees and dry grass ovals—while Hetty screamed—I thought of all these things. It seemed to me that what makes the suburbs a place of love is the people and the things they bring. The things they leave behind too like rosary beads or photographs or the shells they collect on the beach, learning how to be in new places and old places. Full, not empty. Keeping the ground open and hopeful.

Sending so much love from our little home to yours, from West Perth to East Fremantle, Noongar country always,

Kelly and Hetty

Ian Strange: Suburban Interventions 2008–2020

John Curtin Gallery

Presented in partnership with Perth Festival 2020

Initial exhibition dates: 7 February - 24 April 2020

(closed early due to COVID-19)

Images provided by Christina and Kelly