Premonition

11 October 2019

An image study by Gemma Weston

This text was originally written for a performance workshop held by Agatha Gothe-Snape in connection with the exhibition Trying to Find Comfort in an Uncomfortable Chair, held at PICA July 25th – October 6th. Participants were invited to contribute an image and accompanying text, which were then performed as a group reading at the conclusion of the workshop. Slight edits have been made for representation.

—

—

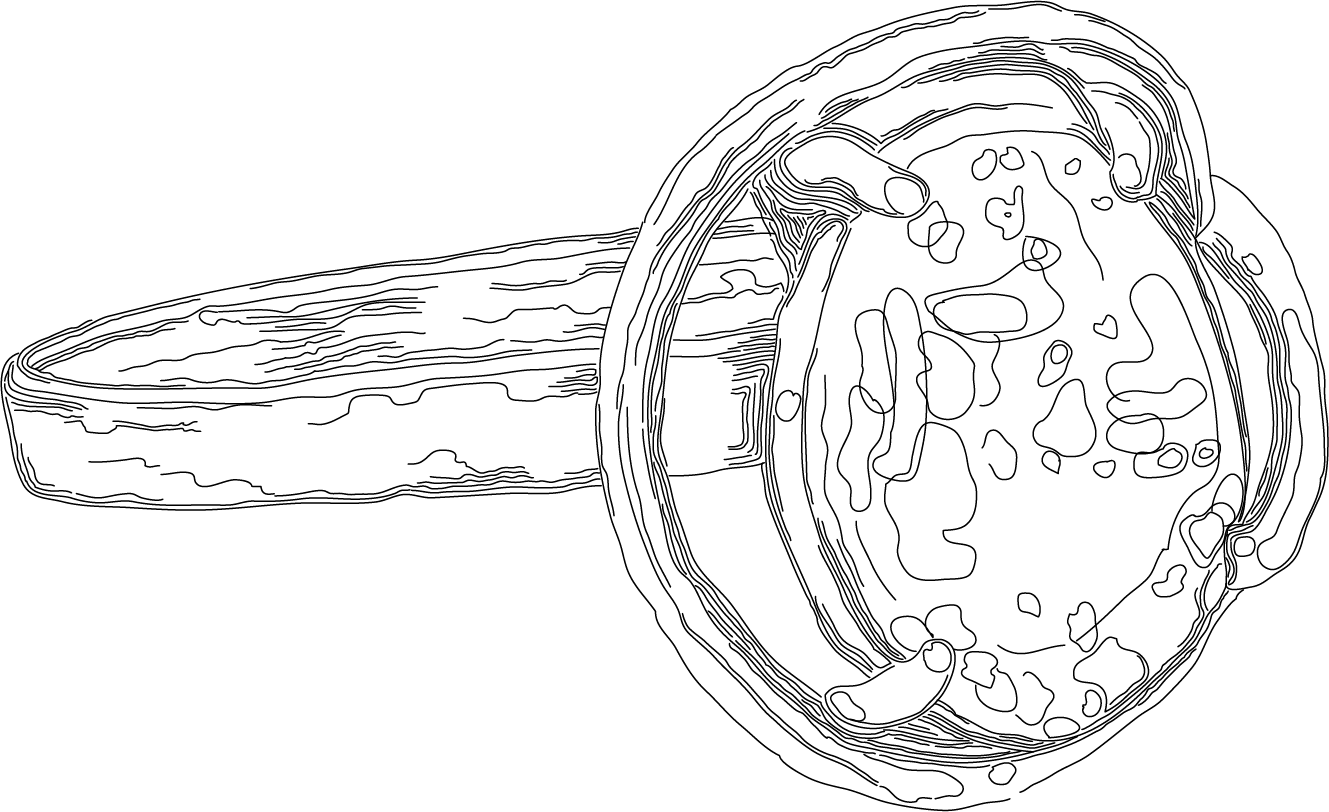

I clipped this image from one of those ‘Around Australia’ photobooks popular in the 1980s and now unpopular in charity stores, around 2012. This particular book was published in 1984, the year of my birth. It is an image of a woman at her home in Coober Pedy, South Australia, where many dwellings – churches, hotels, houses – are built under the ground because of the oppressive heat. The name ‘Coober Pedy’ is an adaptation of the term ‘kupa piti’ - which the website for the Coober Pedy shire refers to simply as an ‘Aboriginal word’ – from Pitjantjatjara or Yankunytjatjara dialects. Apparently, it means ‘white man’s hole in the ground’. Coober Pedy is famous for opal mining. At the time I cut out the image, I had an obsession with the stone that originated from a set of earrings, a ring and necklace my mother owned that I would secretly try on any time I visited my parent’s house in Bunbury.

I love the calm of this woman, in a sweater despite the heat outside, cool and at work in her elegant cave, which is somehow light filled, even underground. I have pinned this image to my wall in successive houses, tried to incorporate it into artworks – to which it has mostly been resistant – for close to a decade now. In 2016 at a party in Adelaide, I was talking to the artist Nicholas Folland about opals, which he like many South Australians is also haunted by. He told me there is a superstition that opals are bad luck, but that it was likely this was encouraged by the diamond industry in the 1980s as a form of economic sabotage to maintain the dominance of the diamond in the midst of opal fever. I told him about the image of the woman that I kept in my house without knowing why. I described her attire and the mural behind her, the watery rainbow facets of an opal painted onto the whitewashed rock.

I had never before this moment conceptualized the painting as an opal, which of course it was. I received this truth as though I was hearing it from another person, feeling it issue from my own mouth, travel back through my ears and settle into my brain, where presumably it must have come from in the first place, as though it was a new idea.

Another Adelaide friend told me that the particular psychic intensity of Adelaide, where disorientating experiences like this and also serial killings occur at higher than average levels, is due to the city being built on a massive quartz deposit that intensifies whatever feelings or energy you bring to the city. It’s true I have only ever had a very good or a very bad time in Adelaide, where my grandfather, it turns out, is actually from.

The same year as my realization about the image, my mother gave me the opal ring and earrings for my birthday, having somehow intuited my obsession with them, along with a diamond ‘eternity’ ring bought for her quite recently by my father. My sisters for their birthdays received, respectively, her engagement ring and a diamond owned by her grandmother. I wear the opal ring every day, the diamonds don’t fit. This surprising and extravagant gift marked the beginning of an ongoing divestment of her more significant possessions that eerily foreshadowed a series of debilitating illnesses. These culminated in her diagnosis, just two years later, with an incurable form of cancer, which is slowly boring tiny holes in her bones.

![]()

I love the calm of this woman, in a sweater despite the heat outside, cool and at work in her elegant cave, which is somehow light filled, even underground. I have pinned this image to my wall in successive houses, tried to incorporate it into artworks – to which it has mostly been resistant – for close to a decade now. In 2016 at a party in Adelaide, I was talking to the artist Nicholas Folland about opals, which he like many South Australians is also haunted by. He told me there is a superstition that opals are bad luck, but that it was likely this was encouraged by the diamond industry in the 1980s as a form of economic sabotage to maintain the dominance of the diamond in the midst of opal fever. I told him about the image of the woman that I kept in my house without knowing why. I described her attire and the mural behind her, the watery rainbow facets of an opal painted onto the whitewashed rock.

I had never before this moment conceptualized the painting as an opal, which of course it was. I received this truth as though I was hearing it from another person, feeling it issue from my own mouth, travel back through my ears and settle into my brain, where presumably it must have come from in the first place, as though it was a new idea.

Some other unrelated but not irrelevant circumstances:

Another Adelaide friend told me that the particular psychic intensity of Adelaide, where disorientating experiences like this and also serial killings occur at higher than average levels, is due to the city being built on a massive quartz deposit that intensifies whatever feelings or energy you bring to the city. It’s true I have only ever had a very good or a very bad time in Adelaide, where my grandfather, it turns out, is actually from.

The same year as my realization about the image, my mother gave me the opal ring and earrings for my birthday, having somehow intuited my obsession with them, along with a diamond ‘eternity’ ring bought for her quite recently by my father. My sisters for their birthdays received, respectively, her engagement ring and a diamond owned by her grandmother. I wear the opal ring every day, the diamonds don’t fit. This surprising and extravagant gift marked the beginning of an ongoing divestment of her more significant possessions that eerily foreshadowed a series of debilitating illnesses. These culminated in her diagnosis, just two years later, with an incurable form of cancer, which is slowly boring tiny holes in her bones.