In the presence of water

18 November 2019

A conversation with Daniel Jan Martin

by Mike Bianco

A conversation with Daniel Jan Martin

by Mike Bianco

Mike Bianco [MB]:I wanted to start out by talking a bit about your background, and when I say background, I really mean your childhood. Are you originally from Perth?

Daniel Jan Martin [DJM]:I grew up down in Torbay, between Albany and Denmark on the southern coast of Western Australia, Perth felt foreign for a long time. Childhood was connected to forest, ocean, small social networks, food from the farm, dogs. I think the childhood impacts all that follows, potentially an obvious statement, but you do see the world through those lenses. I recently ended up in New York for a few weeks. Where this might have felt terrifying for me at a younger age, I can now embrace and love it. I have become an urbanite in many ways…

MB:That’s an interesting insight in light of the work you’ve been doing, which I want to get to in a moment. I also grew up in a semi-rural scenario – a suburb of San Francisco that was in the San Mateo mountains largely filled with Sequoias and Tasmanian Blue Gums… I think it was an experience that has always drawn me back to rural settings, but because of my proximity to San Francisco I also find I am able to navigate urban experiences.

DJM:Interesting. I was recently exploring the Bay Area, and fascinated by how quickly San Francisco breaks away to the north, suddenly in a land of free-thinkers, informal ways of living, along a very unpopulated coastline. Maybe it is the freezing cold water?! The places where we grow are critical in shaping the orientation to our whole environment, where we find a sense of ethic and purpose in things.

MB:You’re currently conducting research through Architecture at UWA, how did you get into the field?

DJM:I got into architecture through studying other things, some ecology, some law, a bit of politics. One day we were talking, writing, talking. There was a lot of optimism when I started studying – an air of hope. Obama had been elected, things felt good for a while. But I didn’t want to be endlessly writing about it. I wanted to be getting involved. I wanted to be working in a space where felt I could be making the physical impacts that needed to follow from the enormity of information, the proofs for the shifts that our cities needed to make. After moving up to Perth, I was missing the family, and driving back and forward to the south coast a lot – the experience of driving past that bush when you drive down, to then have it covered in a fat sand bed when you come back a week later – it impacted how I was seeing things in leafy Nedlands.

MB:I can relate to what you’re saying from my own experience as well. Growing up in California, I saw forests of oaks and rolling hills of golden grasses transformed into multiplexes filled with condominiums and strip malls. It took me a while to understand the pains I was going through seeing such things, and it wasn’t until I came across the writings of Glenn Albrect and his writings on Solastalgia that I began to find a language to help me describe what I was feeling. Would you say notions of solastalgia are a bit of what has been informing your investigations of place, or are there other ways of thinking/feeling/seeing/language which you are more drawn to?

DJM:The writing on solastalgia is very relevant to all of this. I think it is impossible to discuss such things without quickly jumping to emotional impacts, human psychology, and the mind. It is the source of the bind, and the resolution, in many ways. Certainly, working in a biodiversity hotspot, you can see that diminishing, so much can be threatened so quickly. Where even 40,000 people fighting to save the Beeliar wetlands, is not enough to prevent it from being cleared weeks before an election. This is a mean world and a troubling one, even on the very local scale.

I find fighting to be the great antidote to the feelings of solastalgia. When you can use your passion and desire to communicate in order to change a viewpoint, or even express something fundamentally. Possibly that something is original, but it might also be something that is in plain view – a space and an environment that we occupy, but can so easily ignore.

MB:I think that’s a great segway into discussing your practice and what you have been working on for the past several years. I wanted to start out by asking you a bit about your project Swampscapes, your collaboration with Nandi Chinna and Mei Swan Lim. Could you talk a bit about the project and what your role was in it?

[continue reading below︎]

^^^ Swampscapes collaboration between Daniel Jan Martin, Nandi Chinna and Mei Swan Lim. Images courtesy of Daniel Jan Martin.

DJM:This was a lovely project to work on. We all sit in disciplines, and discipline often keeps us inside them. But water is this amazing subject. It inherently brings together people who cross a wide range of areas and backgrounds. I started to get very interested in wetlands as the ground of Perth during my studies in architecture. Perth was, and still remains, this phenomenal terrain of wetlands stretching for hundreds of kilometres across the entire region. So I started to reach out to these other artists, poets and scientists working with wetlands, with water in some form. I found Mei one day with a microphone suspended inside a drain pipe, and thought: we share something. Here is this huge urban catchment, once a rich system, still in fact a rich system, now roaring through this pipe out to the river. Almost unexpressed, and invisible. The transformation of understanding that came from working with Nandi and Mei was incredible. Nandi writes through walking – through this connection of place, pace, motion and language. She sees things in Perth’s ecology that only emerge after many years of immersion. Years ago we met up and I showed her my maps of Perth’s historic wetland terrain – she’d never conceived of the landscape like this. I uncovered these maps from various historical records, overlaying drawings, with a lot of ground-truthing: journeys largely inspired by Nandi. The combination of the maps, which are linear and precise ways of viewing a landscape, with these immersive words and sounds was incredibly rich. Nandi and I spoke for years of exhibiting the maps with her poems – combining the ways of feeling the place – and understanding it. So I brought Mei along and we made some more maps, wrote some more words, recorded some more sounds.

MB:It’s an interesting multi-practice way of ‘knowing’ place. I’m also interested in your use of the map as both a tool and representation. Oftentimes I think of maps as things which not only help us ‘know’ a place - or how to navigate it - but also help us possess it. What are your thoughts on mapping as a form or possessing?

DJM:Maps are entirely possessive. It is impossible to separate them from quite imperial ways of ‘capturing’ place. They have been used to divide and inspire many forms of domination. But I have come to see maps as a language. They are a projection of an environment, ‘a god’s eye view’ perhaps, but they can quantify. They have extreme power, but they can include and exclude, of course. You can inevitably select what you show and what you omit. So they have been used to entrench orthodoxy, but just like words, they have a phenomenal power as a tool for resistance. I think it is an interesting notion too, because we want our research to have power, we want to communicate and have impact. And we need to fight against maps, we need to fight with boundaries, with spatial plans for sprawl that were enacted 30 years ago. Maps give us the power to resist and call things out.

MB:I think that’s a nice way of reframing how maps can work. It seems like this reframing is part of your ongoing project the Whole Perth Catalogue, a project which I find exciting both in its reference to the now famous Whole Earth Catalogue by Stewart Brand, and it’s reminiscent qualities to one of my favorite projects in the world - Matthew Coolidge’s Centre For Land Use Interpretation. Could you talk a bit about the Whole Perth Catalogue, it’s inspiration, your intentions, and your aspirations for it?

DJM:It came around the beginning of my PhD, when I inevitably wanted to achieve, within the aspiration of a single project, something that I realised needed to become a whole career of work. It is about representation really. I have studied in a discipline that values projection over representation in many ways. The need to project alternative futures is critical. But the projection of these futures can only be accepted by society if there is a notion of what the problems or issues are, what the values are, environmentally, culturally. What are the voices that need to be heard that are quieter, not dominant, but vital? I think understanding these things is essential for designers, as much as the clients or public that receive, use, engage with the outcomes.

The Whole Perth Catalogue became a collection of observations, of stories and little projects that I had been working on over the years of engaging with Perth, its urban environment and coming to understand this ecoregion. It is a phenomenal place, and to explain that is an essential foundation. I would love for it to become a very large collection of projects, of reseeings, with as many authors as possible. I would love for Traditional Owners to contribute to layers to this. It isn’t so much a project as a framework for hanging things of importance.

MB:It’s interesting that you see the project as a platform - as a way to re-frame and resee what is already here. Part of my desire to interview you came from a recent posting you had in regards to the project and clay deposits in the area. As someone with a background in ceramics, and a keen desire to ‘know place’ it was exciting to find someone who was actively exploring the material qualities of the area. Having said that, I also question my own use of your project to literally mine Perth for a material to use in my own practice. Maybe this is a problem in my own practice, but I wonder what your thoughts are about the project becoming a platform for people to extract even more from a land that has already been asked to give so much?

[continue reading ︎]

DJM:I think the clay maps are interesting. Sometimes in the things I have posted, I have omitted the place names. Not because I want to keep it secret, but because things have a way of going ‘viral’ on the internet. Places can be spoiled by the hashtag. The clay maps are drawn at such a large scale, and cross so many boundaries, that you would have a hard time using them to find clay I think... But the conceptual problem remains. In coming to ‘understand’ something you get given an opportunity of controlling it. So it gets to that wholistic place of educating around ecology, with humans a part of that system.

I worked with a very good friend, Adam Bahar, on the design of the Catalogue. Which became quickly utilitarian, much like a newspaper, or even a wunderkammer, a containment of objects and topics under headings. I am uncomfortable with that colonial reference in the work. But, like with the maps, I think it might be a ploy: can objects of resistance, collections of reseeing be framed as a structure and certitude? Does it give the work more weight? I think it might…

MB:It’s a good question. Again, I think it all comes down to use - use of place, use of materials, use of data. The project certainly creates a database for knowing Perth under a certain set of terms, but how it gets used is relatively open. How I use it as a potter and educator might be very different than how a mining company might look at it. Then there’s the way you use it, and as you said, your focus is largely on education. Have there been any instances where you have used the the Whole Perth Catalogue beyond the boundaries of a computer screen for educational purposes?

DJM:I think a lot of the talking I have been doing in the studio classroom, in government departments, at workshops of various kinds, is a communication of that project. Although most of our data is now open, there is still a cloud around it, it is so rarely communicated and visualised. It is all already abundant and available to the miners, the developers, and the economic demographers. The simple exercise of overlaying a dataset from one government department with a dataset from another government department to highlight a conflict, is now the role of the researcher.

So to put the data into the public domain in a communicative way, is a step forward. If it is then underpinned by an ethic, I think that’s where it can begin to educate. Many of these issues are consistently debated. There is a risk in a project like the Whole Perth Catalogue, which purports to be objective, through its mapping, or its tone, taking on a polemic. But maybe it needs to. I feel that it is countering a whole series of very oppressive actors.

MB:I think it’s a good distinction to make. I think in this time where everything seems to be about data and data ownership, giving - let alone translating – data from the private or government sectors for the public is both political and a highly generous act. If nothing else, in the example of the clay maps, the Whole Perth Catalogue made this place knowable to me in ways that have been incredibly difficult to do on my own.

DJM:I constantly question how things are communicated and presented. The Whole Perth Catalogue gives the landscape a weight or a force within a domain where it is otherwise weak. The ecology consistently becomes the victim, the ninth thing on a list. Is there a way of releasing these ‘reseeings’ in an objective way? There may not be. But they open up a space for a range of responses to emerge. A range of debates to begin, for artists and designers to respond. I think that space is one that feeds on all forms of ‘knowing’ including the maps; the locations of drains beneath our feet, the presence of a historic wetland, or the flight path of the red-tail black cockatoo across a particular margin of the Coastal Plain. It is also about seeing a longer-term notion, to see a landscape in time or in flow, as interconnected. These are ways of thinking that contemporary human systems, our boundaries, our codes ignore. There is a consistent desire for the short-term wealth of an individual, a corporation, or a government, over the medium-term or long-term health of society, or an environment. It comes from seeing in boundaries, in surfaces, and in compressed time.

MB:Speaking of education and thinking about the long-term health of a society, could you talk about your involvement with the recent book In Time With Water: Design Studies of 3 Australian Cities?

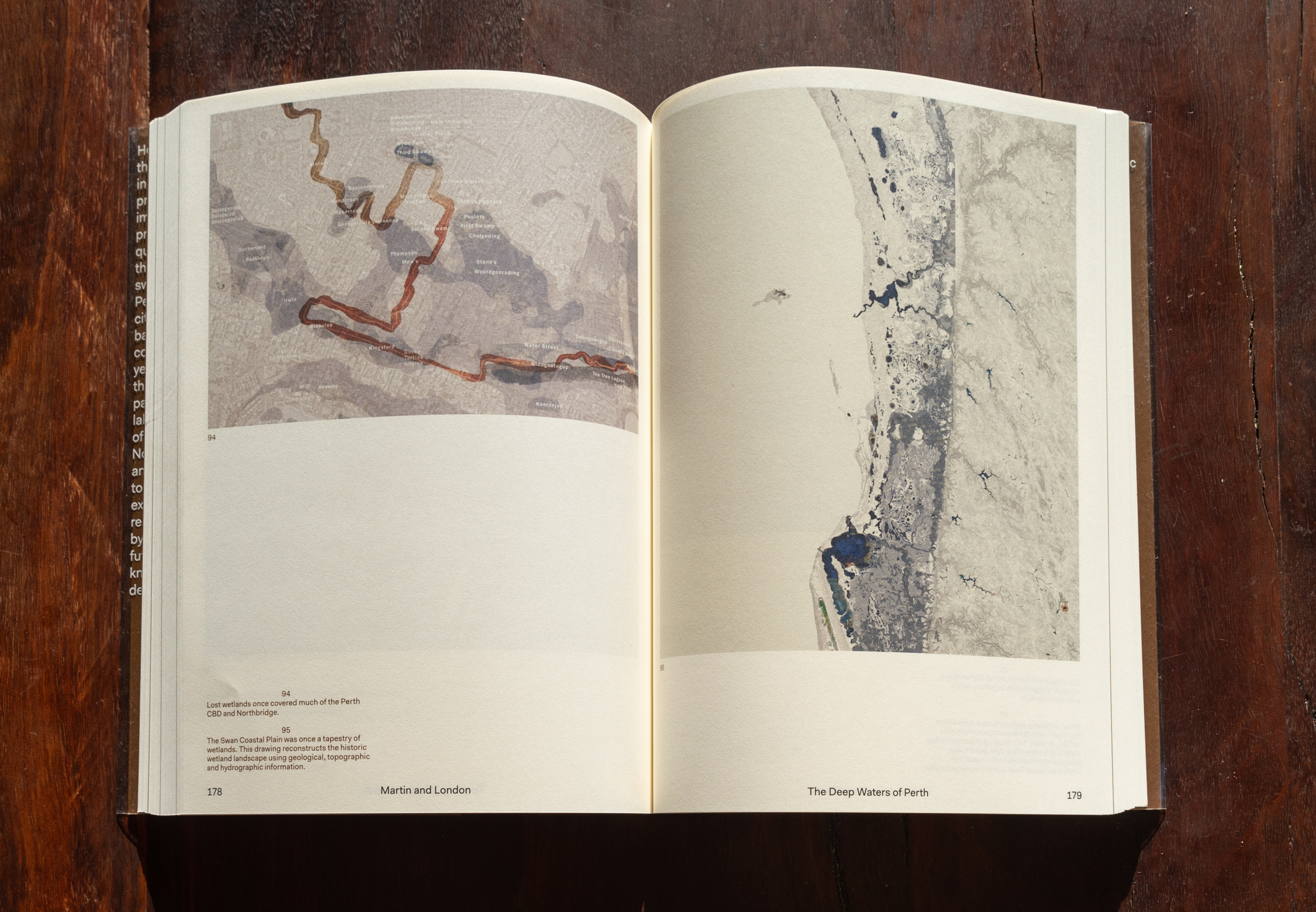

DJM:In Time With Water was a really interesting project. It was a real privilege to jump on board with this research team after graduation. It was led by Nigel Bertram at Monash who has a marvellous ability to traverse scale: from the pragmatics of architectural practice to the sense of an entire urban landscape within its catchment and context. A few things really stood out in that project. We worked alongside research teams from Melbourne and Brisbane and we were consistently reminded how unique Perth is. Underlying Perth are phenomenal aquifer systems, which do not factor in Melbourne or Brisbane. We are dry in the sense we get so little summer rainfall, but wet in the sense that we get more rain than Melbourne and Hobart – but it all comes in winter, and soaks into the ground where it sits beneath the city. So Perth is ‘The Wet City’ (my PhD title) in many respects. Of course we extract huge amounts of water from these aquifers – this is how we can sustain such green and grassy open spaces all summer long. The design approaches we developed through several architecture studios at UWA were all about groundwater. We were very fortunate to work with environmental engineers, ecologists and hydrogeologists in understanding these systems and translating them into design briefs. This was the other very impactful part of the In Time With Water project, the involvement of students across Monash University, The University of Western Australia and The University of Queensland. There were something like 70 students who all contributed to the publication through analytical drawing, design schemes and documenting site. So a very connective project, and a publication which captured a wonderful process of coming to understand our cities through the lens of water.

MB:The publication is quite beautiful, and at nearly 300 pages, loaded with content, but how do you imagine what you all have done as a research team will translate into policy and practice?

DJM:This is such an important question. Firstly, though, on the beauty of the book – we owe a lot of that to Warren Taylor and the graphics team at MADA (Monash Art Design Architecture) who approach the art of book-making which such sincerity. It was a joy to work so closely with these designers in artists in compiling the publication.

[continue reading ︎]

^^^ In Time With Water: Design Studies of 3 Australian Cities, various pages. Images courtesy of Daniel Jan Martin.

To put many of these things into practice on the one hand seems really very simple. In Perth, we build almost exclusively in heavy brick and tile, on heavy slabs. This necessitates an approach to construction which is heavy from the outset, with many metres of sandy fill required to produce the same site-type, the same surface condition, enabling that form of urbanisation that our building culture demands. Lightweight methods of construction immediately free up the ground, it means ecological space and hydrology can be retained, and not erased. Technologically it is possible, materially we have factories here that are producing more engineered timber than anywhere else in the country (and shipping 80% of that product to the eastern states). The challenges are in policy and how these decisions are regulated, against the short-term economic pressures, and the inertia of our building culture. The book is a call for creativity to be embraced by governments, by decision makers and developers in navigating these challenges, and greater collaboration between design and these urban actors is now vital. We need much greater coordination between designers, artists, creative minds, and decisionmakers, governments, and policymakers. To understand the economic constraints and work within them is one thing, to communicate the long-term benefit of working with nature and not attempting to erase or control it another critical component. It falls upon researchers to demonstrate how our urban environments will be changing with a growing population and drying climate, and to visualise and represent the alternative futures.

MB:I can definitely relate to this as an artist with an ecologically-minded and research-driven practice. I’ve worked on a number of projects which have attempted to engage the public to engage in “wicked problems” that will directly impact them. The trick is often in translation, and as an artist I’m always having to navigate between creating a space of contemplation for my audience and being co-opted as a science/policy communicator for someone else's agenda. I think the perpetual problem we face is trying to connect what we do in research with what gets enacted as policy, and sometimes I worry that this process happens at a rate that is out of sync with the rates of change that we see threatening our environments. As such, what are your thoughts on more direct forms of action?

DJM:I think it falls upon researchers now to be communicating increasingly with an aware and interested public, not only about the climate emergency, and all the urban implications of this, but to communicate the wonder of our ecology and place. It is certainly an issue for our creative integrity as designers and artists when science might co-opt us as communicators, but the scientific community urgently needs collaborators who are visual and spatial. There does need to be dialogue and a mutual respect between fields.

The rate of change is slow, and, my concern is that public awareness is still so low around many of the urban challenges we face. This means that the political will is not emerging and action does not follow. The climate rallies have been fantastic and extremely empowering as a researcher in this field. But they are still about mitigation. Which is of course essential. The story of adaptation is one we all have to be understanding now. And that falls upon the Elders, the poets, the artists, the scientists, the urbanists, and the filmmakers. One of my favourite projects in Perth recently was Boorna Waanginy – The Trees Speak, not only for its very sincere telling of the biodiversity story, but for the phenomenal public embrace of that story. Something like 250,000 people, it was a festival for biodiversity. These create the spaces to have discussions with people about place and about the need for agency over our built environment. I think the majority of the Perth public feel very disconnected from the urban agendas of our city, so the communication question here is huge.

MB:I thought I’d wrap up our conversation by asking about some of the things that are informing your practice these days – what are you reading, listening to, and watching?

DJM:I am currently listening to a lot of the ECM catalogue. Much of this music makes for a clean and clear headspace. I find the recent live work of artists Nils Frahm and Peter Broderick to be very exciting in their blend of beautiful melody and gradual evolution. I am currently singing in three choirs which occupies much of my time. There is such a social role for singing that many of us have lost. It brings people together in a fundamental way. On my reading list at the moment has been the writings of an exciting lineage of French landscape architects: Corajoud, Desvigne, Chemetoff, Girot. Rarely translated to English, and a delightful world to be uncovering. I often return to the work of Australian author Peter Carey, who I love, particularly his partially fictional novel 30 Days in Sydney: A Wildly Distorted Account. Peter Carey’s accounts of place and architecture are always potent. I have just started reading Tropic of Orange by Karen Tei Yamashita which is impressive so far, I am looking forward to the unfolding cartographic illusions. I watch very little. But I did recently enjoy Shooting the Past, an old 90s TV drama by Poliakoff. It follows the story of a rich photographic archive, abandoned. A trove of big data, when accessed and ‘mined’ can produce a kind of magical picture through the assemblage of many pieces of the past. That research exercise fascinates me...