I Feel A Song Coming On

17 May, 2020

A response by Ben Rodin to PREPPERS

Fremantle Arts Centre

A response by Ben Rodin to PREPPERS

Fremantle Arts Centre

Reviewing Preppers has become an exercise in trying to

understand how we might discursively engage with an apocalypse, whether it be bushfires, the climate crisis, the erosion of democratic rights, or the pandemic that meets us now.

While criticism and analysis have always had an affinity for recency, somehow it feels like there has never been more to know and consider, that the gallery of experts we can rely on to understand the world is constantly expanding and shrinking. To borrow from New Zealand’s Prime Minister, our television hosts have become epidemiologists.

Adjacent to this, Australian writer Sean Kelly recently made some telling observations in The Point about the way we congregate and communicate in the current moment:

"There are, I feel, two types of writing now. Writing about the virus, and writing that claims to be about other subjects but which is really about the virus. Another way to say this: there is at present only one type of writing. I find this is true of everything being written, but I find it, too — I don’t think I’m the first to say this — about everything that was written previously, whether novels, or scripts, or that article about five rich men."

As a result, it's also hard to know how much any kind of art matters right now. The comfort of being streamed in a person's bedroom, listened to on a phone, or analysed by housemates at a kitchen table seems rote compared to the loss of a precarious livelihood, or a life.

Furthermore, the federal government’s lacking policy and economic response suggests the arts have and never will be more than a distraction for them. Troubling questions abound about our industry’s choices of rhetoric, the business models we have used and our broader sense of social solidarity with the audiences we want to reach.

But those beget even bigger dilemmas: How does one distinguish concern about displaced friends, communities and scenes regarding the collapse of their industries from concern about the safety of older and more vulnerable members in our community, or the disproportionately punitive measures that racial and ethnic minorities are facing globally?

I stop playing with a dark scenario when all of the other, bigger and darker scenarios make this scenario seem less significant.

While criticism and analysis have always had an affinity for recency, somehow it feels like there has never been more to know and consider, that the gallery of experts we can rely on to understand the world is constantly expanding and shrinking. To borrow from New Zealand’s Prime Minister, our television hosts have become epidemiologists.

Adjacent to this, Australian writer Sean Kelly recently made some telling observations in The Point about the way we congregate and communicate in the current moment:

"There are, I feel, two types of writing now. Writing about the virus, and writing that claims to be about other subjects but which is really about the virus. Another way to say this: there is at present only one type of writing. I find this is true of everything being written, but I find it, too — I don’t think I’m the first to say this — about everything that was written previously, whether novels, or scripts, or that article about five rich men."

As a result, it's also hard to know how much any kind of art matters right now. The comfort of being streamed in a person's bedroom, listened to on a phone, or analysed by housemates at a kitchen table seems rote compared to the loss of a precarious livelihood, or a life.

Furthermore, the federal government’s lacking policy and economic response suggests the arts have and never will be more than a distraction for them. Troubling questions abound about our industry’s choices of rhetoric, the business models we have used and our broader sense of social solidarity with the audiences we want to reach.

But those beget even bigger dilemmas: How does one distinguish concern about displaced friends, communities and scenes regarding the collapse of their industries from concern about the safety of older and more vulnerable members in our community, or the disproportionately punitive measures that racial and ethnic minorities are facing globally?

I stop playing with a dark scenario when all of the other, bigger and darker scenarios make this scenario seem less significant.

Reviewing a show about prepperdom and survival during a rapidly

changing political and economic environment is fraught, but the apocalypse is so hot right now.

Individualised militarism is rife, the current pandemic is exacerbating long-simmering geopolitical conflicts, and governments the world over are embracing an array of troubling measures to manage the crisis, stretching from new forms of surveillance technology through to the complete abdication of state responsibility.

Likewise, the public have also straddled the line separating utility and desire: Fleshlights, toilet paper, seedlings, alcohol (sanitisers and beverages), N95 masks, Nintendo Switch consoles and yoga mats are but several items that have experienced increased demand. The resulting anxiety from customers has marked supermarkets as sites ripe for conflict, sparking both headlines and shareable content.

Preppers then, is nothing if not on the pulse, synthesising these concerns with aplomb. The show’s core artists and curators (Loren Kronmeyer, Guy Louden and Dan McCabe) clearly design the exhibition with the world's doom-laden trajectory in mind, a journey that has only accelerated since 2016’s twin traumas of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump.

"Even though I don't like the direction it's unfolding in, those observations are coming from somewhere and that is being affirmed by the way that things are playing out and it's not my imagination," Loren says to me during a Skype interview.

It’s a fair point. Two months after our interview, the rapid escalation of COVID-19 is another signal, to borrow from prepper jargon, that shit has hit the fan.

However, from Loren's end, the show seeks to disrupt the assumptions that are integral to the dominant authorship of the survivalist narrative.

"[You’re] going into the show, with the understanding that the word survival presumes that you haven't already, for example, lived through an apocalyptic event; [that] to be prepping for the doomsday implies that doomsday hasn't already occurred,” she explains.

“And that's simply not the case for a lot of cultural groups."

She references crises such as HIV, colonial struggle, and the earth’s dwindling biodiversity, alluding to the people that have and continue to negotiate those experiences first-hand.

"The culture that I'm interested in creating is culture that affirms the survival skills that are already being practiced by people simply surviving late capitalism."

Individualised militarism is rife, the current pandemic is exacerbating long-simmering geopolitical conflicts, and governments the world over are embracing an array of troubling measures to manage the crisis, stretching from new forms of surveillance technology through to the complete abdication of state responsibility.

Likewise, the public have also straddled the line separating utility and desire: Fleshlights, toilet paper, seedlings, alcohol (sanitisers and beverages), N95 masks, Nintendo Switch consoles and yoga mats are but several items that have experienced increased demand. The resulting anxiety from customers has marked supermarkets as sites ripe for conflict, sparking both headlines and shareable content.

Preppers then, is nothing if not on the pulse, synthesising these concerns with aplomb. The show’s core artists and curators (Loren Kronmeyer, Guy Louden and Dan McCabe) clearly design the exhibition with the world's doom-laden trajectory in mind, a journey that has only accelerated since 2016’s twin traumas of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump.

"Even though I don't like the direction it's unfolding in, those observations are coming from somewhere and that is being affirmed by the way that things are playing out and it's not my imagination," Loren says to me during a Skype interview.

It’s a fair point. Two months after our interview, the rapid escalation of COVID-19 is another signal, to borrow from prepper jargon, that shit has hit the fan.

However, from Loren's end, the show seeks to disrupt the assumptions that are integral to the dominant authorship of the survivalist narrative.

"[You’re] going into the show, with the understanding that the word survival presumes that you haven't already, for example, lived through an apocalyptic event; [that] to be prepping for the doomsday implies that doomsday hasn't already occurred,” she explains.

“And that's simply not the case for a lot of cultural groups."

She references crises such as HIV, colonial struggle, and the earth’s dwindling biodiversity, alluding to the people that have and continue to negotiate those experiences first-hand.

"The culture that I'm interested in creating is culture that affirms the survival skills that are already being practiced by people simply surviving late capitalism."

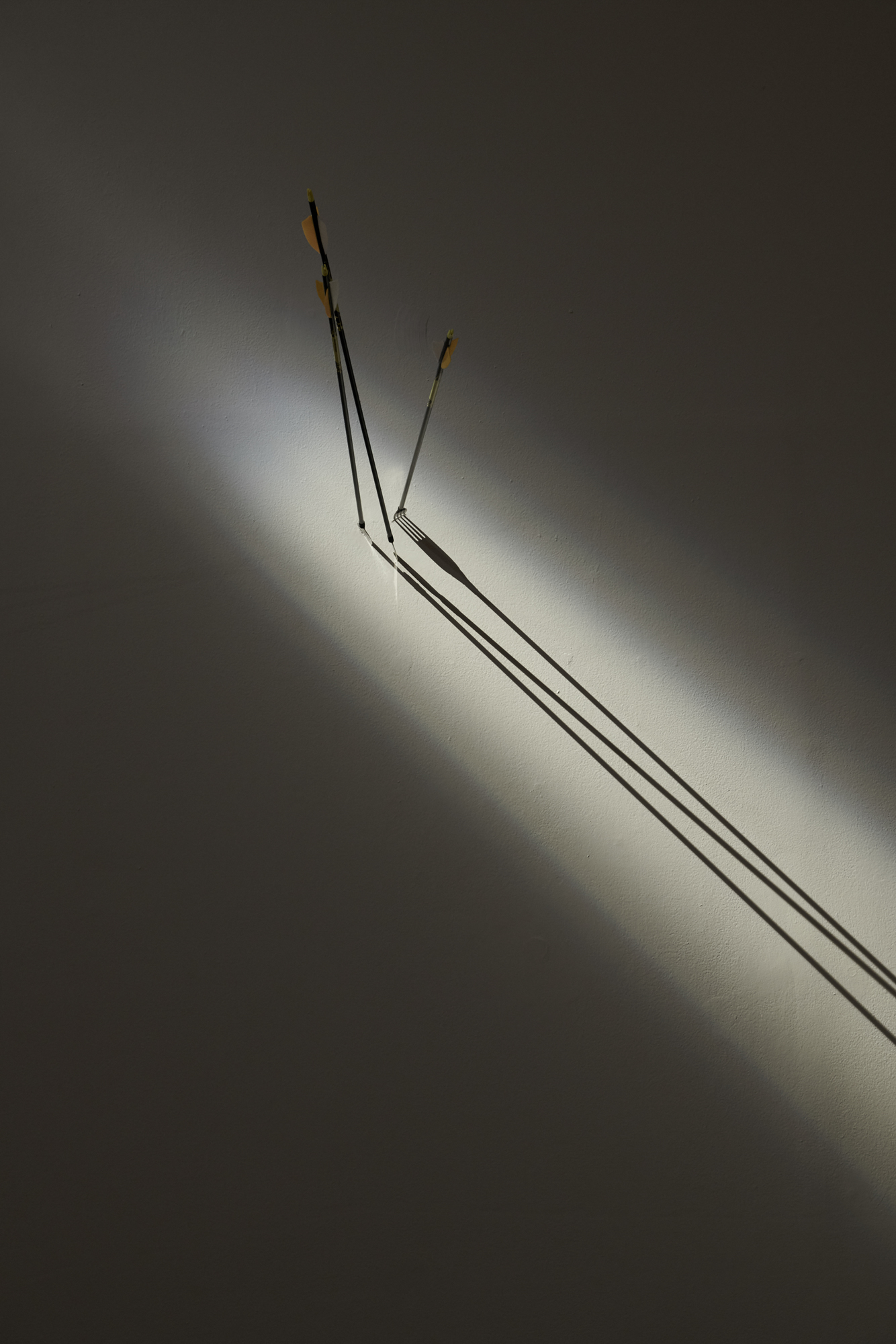

Loren’s work uses archery as its starting point to grapple with

the exclusionary white and male presences often associated with the prepper

phenomenon. Despite strong intentions, it falls short of its aims.

"There's so much energy around this sort of butch, deadly, masculine survivalist energy, and my intent from the beginning of this process was to really bring a queering of that and to bring in a troubling of that aesthetic, and to explore how that aesthetic translated across different bodies and sensibilities,” she tells me during our chat.

But as exhibited in the show, the work has a limited relationship to the complexity of queerness. The notion of role playing is something that the show struggles with as a whole, with identity-based ideology (queerness, locality, masculine bravado) used to create works that reproduce a specific but limited understanding of prepperdom (that this spectacle is both a terrifying and exciting thing).

A similar problem is at play with Thomas Yeomans’ prints, which use nationalism and queerness as the pre-text to speculate on the potential flags of a future uprising, flattening possibilities into aesthetic returns that leave their questions unanswered.

Ultimately, in Loren’s work, the attempts to disrupt the myths of masculine survivalism are undermined by the tropes used to highlight its subversion. The Boy's Own Annual book, the polygraph and archery equipment are symbols that end up re-affirming the larger military and consumption-based goals of prepperdom, because they don’t read as having a clear purpose separate to the works around it.

While other elements of Loren’s installations, such as the inscriptions on the arrow shafts or the archery target pattern that is stuck to the hay bales, create the troubling she aspires for, these moments also feel difficult to distinguish amongst the other materials. It’s hard not to feel that the work is too ambiguous for its own good: While the violence of disruption promised is more exciting than what transpires in the work, it still feels like it would be a frustrating half-measure. If we’re going to be violent and queer and survivalist, why don’t we go the distance and burn it all down?

If we’re speculating, why don’t we tear our antagonists apart?

"There's so much energy around this sort of butch, deadly, masculine survivalist energy, and my intent from the beginning of this process was to really bring a queering of that and to bring in a troubling of that aesthetic, and to explore how that aesthetic translated across different bodies and sensibilities,” she tells me during our chat.

But as exhibited in the show, the work has a limited relationship to the complexity of queerness. The notion of role playing is something that the show struggles with as a whole, with identity-based ideology (queerness, locality, masculine bravado) used to create works that reproduce a specific but limited understanding of prepperdom (that this spectacle is both a terrifying and exciting thing).

A similar problem is at play with Thomas Yeomans’ prints, which use nationalism and queerness as the pre-text to speculate on the potential flags of a future uprising, flattening possibilities into aesthetic returns that leave their questions unanswered.

Ultimately, in Loren’s work, the attempts to disrupt the myths of masculine survivalism are undermined by the tropes used to highlight its subversion. The Boy's Own Annual book, the polygraph and archery equipment are symbols that end up re-affirming the larger military and consumption-based goals of prepperdom, because they don’t read as having a clear purpose separate to the works around it.

While other elements of Loren’s installations, such as the inscriptions on the arrow shafts or the archery target pattern that is stuck to the hay bales, create the troubling she aspires for, these moments also feel difficult to distinguish amongst the other materials. It’s hard not to feel that the work is too ambiguous for its own good: While the violence of disruption promised is more exciting than what transpires in the work, it still feels like it would be a frustrating half-measure. If we’re going to be violent and queer and survivalist, why don’t we go the distance and burn it all down?

If we’re speculating, why don’t we tear our antagonists apart?

I wonder though, if I am in any position to complain about a

failed conceit given my own relationship to the social contract – itself a

holdover from classical liberalism – is similarly flaky on a day to day basis.

Suspended social spaces are suddenly charged with a spiritual level of significance: Going to the pub (with friends), playing footy (with friends), watching footy (with friends), going to a gig (with friends), driving out to a regional art gallery (with friends).

Meanwhile, functional tasks attach to themselves a self-aggrandising level of cultural capital: Sourdoughs (at home, for a few), drinking (alone), cooking (alone), exercising (alone), all documented online for the many to gawk at. The aesthetics of isolation in Inner Northern Melbourne - Monsteras and Macbook Pros in living rooms, clean KeepCups pushed to the back of kitchen cupboards - look and feel the same as those in Perth or Edinburgh or London.

Telling some people that you didn't like large portions of an art show (writing at home, alone, for other people, reading, alone) but qualifying it was made by people you like and respect feels of a piece with this.

This apocalypse, as you see it and feel it, doesn't look anything like the apocalypse depicted in Preppers; the aesthetics and conceit of reviewing the show feel similarly untrustworthy.

You converse with a friend, trying to process another thing that happened while you are confined to your home. Lots of things had happened: A pandemic, an economic crisis, mass death, unemployment, closures – of businesses, of schools, of university campuses.

You wonder out loud, as loud as one can wonder into WhatsApp in an otherwise empty room, how you'll explain your professional choices to their kids, or your siblings’ kids, years from now, when and if you get through these things.

"Well, I wrote a lot of important stories," you will embellish, at a barbecue with more than 10 people in attendance. Your friends' eyes glaze over, their attention shifts elsewhere.

You're guilty as charged. You change mid-course and the truth slips out: "I also shit posted all day while working from home.”

︎︎︎

Suspended social spaces are suddenly charged with a spiritual level of significance: Going to the pub (with friends), playing footy (with friends), watching footy (with friends), going to a gig (with friends), driving out to a regional art gallery (with friends).

Meanwhile, functional tasks attach to themselves a self-aggrandising level of cultural capital: Sourdoughs (at home, for a few), drinking (alone), cooking (alone), exercising (alone), all documented online for the many to gawk at. The aesthetics of isolation in Inner Northern Melbourne - Monsteras and Macbook Pros in living rooms, clean KeepCups pushed to the back of kitchen cupboards - look and feel the same as those in Perth or Edinburgh or London.

Telling some people that you didn't like large portions of an art show (writing at home, alone, for other people, reading, alone) but qualifying it was made by people you like and respect feels of a piece with this.

This apocalypse, as you see it and feel it, doesn't look anything like the apocalypse depicted in Preppers; the aesthetics and conceit of reviewing the show feel similarly untrustworthy.

You converse with a friend, trying to process another thing that happened while you are confined to your home. Lots of things had happened: A pandemic, an economic crisis, mass death, unemployment, closures – of businesses, of schools, of university campuses.

You wonder out loud, as loud as one can wonder into WhatsApp in an otherwise empty room, how you'll explain your professional choices to their kids, or your siblings’ kids, years from now, when and if you get through these things.

"Well, I wrote a lot of important stories," you will embellish, at a barbecue with more than 10 people in attendance. Your friends' eyes glaze over, their attention shifts elsewhere.

You're guilty as charged. You change mid-course and the truth slips out: "I also shit posted all day while working from home.”

︎︎︎

^^^ images 1- 4, photography by Rebecca Mansell

When I speak to Tiyan Baker in January, we are both at home

staying with our families. I'm on the metropolitan-rural fringes of Perth,

while Tiyan is in Malaysia for a residency.

She openly acknowledges that her work for Preppers, "Bamboo Paradise", is a pointed departure from the more heavy-handed constructs the show concerns itself with.

"I was actively not wanting to indulge in that sort of imagery, just because I actually find it boring... a bit masturbatory really,” she says, referring not to the other artists' work, but the broader aesthetics of prepperdom. “I came up with my own response… which was more centred around, maybe a bit more [of a] culturally diverse perspective on survivalism.”

Tiyan is cognisant of how her work differs from its surrounding environment while offering a thematic resonance with the exhibition. The three channel video installation considers the culture of survivalism through the prism of a popular YouTube channel dedicated to the contemporary construction of what the artist describes as "primitive lifestyle" content, including structures like pools, slides and temples.

"I think that the YouTube channel and [what] all the kind of dozens and dozens of channels that are exactly the same really play with is what does surviving really look like? What does surviving off the grid look like?" Tiyan asks rhetorically.

"It doesn't have to look like this... frugality... It actually can look really beautiful and it's very playful, like they make these slides; they decorate the sculptures in really kind of poignant, interesting ways... But I think it maybe tied up with the other works in that it [the subject] was still [offering] an industrialised, commercialised approach to ideas of prepping."

I initially deceived myself when viewing the installation: I wondered whether the work’s low-key presence was arch and satirical in the same way that other parts of the show, most specifically Guy’s work, aim to be. After my conversation with Tiyan though, the light-footedness instead scans as an attempt to disrupt the cultural norms that drive the rest of the show, introducing plurality into the gallery space.

"I wanted it to be refreshing; I wanted it to be like a breath of fresh air… just really losing that sort of sense of Western rigidity and seriousness, and really trying to inhabit another sort of mentality," she says at one point.

Asked to discuss who she was thinking of when she made her work, Tiyan offers an insight that for me, inadvertently revealed the limitations of the show that surrounds it.

"I made it [the work] for an audience that would not be necessarily literate in South East Asian culture... People who might not have considered that prepping could look like anything else… [that] the end of the world could look like anything else in another culture.

She openly acknowledges that her work for Preppers, "Bamboo Paradise", is a pointed departure from the more heavy-handed constructs the show concerns itself with.

"I was actively not wanting to indulge in that sort of imagery, just because I actually find it boring... a bit masturbatory really,” she says, referring not to the other artists' work, but the broader aesthetics of prepperdom. “I came up with my own response… which was more centred around, maybe a bit more [of a] culturally diverse perspective on survivalism.”

Tiyan is cognisant of how her work differs from its surrounding environment while offering a thematic resonance with the exhibition. The three channel video installation considers the culture of survivalism through the prism of a popular YouTube channel dedicated to the contemporary construction of what the artist describes as "primitive lifestyle" content, including structures like pools, slides and temples.

"I think that the YouTube channel and [what] all the kind of dozens and dozens of channels that are exactly the same really play with is what does surviving really look like? What does surviving off the grid look like?" Tiyan asks rhetorically.

"It doesn't have to look like this... frugality... It actually can look really beautiful and it's very playful, like they make these slides; they decorate the sculptures in really kind of poignant, interesting ways... But I think it maybe tied up with the other works in that it [the subject] was still [offering] an industrialised, commercialised approach to ideas of prepping."

I initially deceived myself when viewing the installation: I wondered whether the work’s low-key presence was arch and satirical in the same way that other parts of the show, most specifically Guy’s work, aim to be. After my conversation with Tiyan though, the light-footedness instead scans as an attempt to disrupt the cultural norms that drive the rest of the show, introducing plurality into the gallery space.

"I wanted it to be refreshing; I wanted it to be like a breath of fresh air… just really losing that sort of sense of Western rigidity and seriousness, and really trying to inhabit another sort of mentality," she says at one point.

Asked to discuss who she was thinking of when she made her work, Tiyan offers an insight that for me, inadvertently revealed the limitations of the show that surrounds it.

"I made it [the work] for an audience that would not be necessarily literate in South East Asian culture... People who might not have considered that prepping could look like anything else… [that] the end of the world could look like anything else in another culture.

I still think about this now. Tiyan’s work, and the words that

support it, offer a considerably more realist conception of the world than the

rest of the exhibition. It’s less generalist, a more gently observant read of

how others engage with the idea of survival historically. (Her observations

also overlap with Loren’s, though their works differ considerably).

“Bamboo Paradise” feels more lived-in and less postured than the other work in the exhibition. It offers a way of making and thinking that lets its subjects live, and calmly does the work of documenting that. It is blithely unconcerned with the outward projection of confidence or selfhood, something that the other works are especially burdened by.

Writing here and now, I’m left with another impression: That much of what constitutes our current crisis is the sudden realisation that the decades and centuries of canon drawn from fictions and poorly written truths has become useless after the minutes and months of a new reality that has little to do with the source material of our imaginations.

On an early morning in the middle of May, our autumnal lockdown subsides, only for Melbourne’s winter to beckon. I stop typing and crawl under my bedsheets in search of comfort, as if I will hibernate until I can recognise the world that I live in again.

“Bamboo Paradise” feels more lived-in and less postured than the other work in the exhibition. It offers a way of making and thinking that lets its subjects live, and calmly does the work of documenting that. It is blithely unconcerned with the outward projection of confidence or selfhood, something that the other works are especially burdened by.

Writing here and now, I’m left with another impression: That much of what constitutes our current crisis is the sudden realisation that the decades and centuries of canon drawn from fictions and poorly written truths has become useless after the minutes and months of a new reality that has little to do with the source material of our imaginations.

On an early morning in the middle of May, our autumnal lockdown subsides, only for Melbourne’s winter to beckon. I stop typing and crawl under my bedsheets in search of comfort, as if I will hibernate until I can recognise the world that I live in again.

I sometimes wonder if I need to be more forgiving when I perceive

my peers as failing to successfully grapple with the darkest speculations and fictions

that are gripping the world. It's not as if I've done a much better job myself.

"Researching preppers is fucking depressing," Dan admits to me in January, almost as an aside.

We’re in a cafe near the Fremantle Arts Centre. The summer weather is typically pleasant, but I’m certain the uneasiness I feel is coming from motorcycles revving at the traffic lights rather than Fremantle Oval, or the rainbow arrangement of shipping containers sitting several hundred metres away. Nevertheless, between the Dockers and a Marcus Canning installation, exhibiting work about prepperdom in Freo makes a lot of sense.

"You see the worst of the internet... it's a lot of white, alt-right, hetero alpha males. That's... a big part of prepper culture: It's not what you want to surround yourself with."

Projecting a carbon-black sheen on customised camouflage patterns, with names that draw from both the industrial military complex and a mix of native and introduced floral patterns, Dan’s prints suggest they could easily be used in a hypothetical local conflict.

Euco Splinter. Marlock Tiger Stripe. Pommy Plane DP. Red River Biccy.

The motivation for this, in Dan's re-telling, suggests an attempt at resolving the research-life art axis: he talks about owning his first home and being part of a community, things that would make someone want to escape prepperdom’s worst impulses.

The focus of the Preppers project has evolved since 2016, and so too has Dan's interest in the patterns. From an extremely broad engagement with military design - "What I was really interested in is how these different patterns can be used for different means by different people to different aims and outcomes" - to wanting to speculate and consider possibilities – "This one [the Preppers exhibition] was very much looking at the future."

Dan's work has an admirable technical command, but nevertheless does itself few favours with its presentation. Rendering the localised military patterns within the "Compound" installation, provokes other questions though – Who are these localised designs actually for?

To be blunt: Why is native flora being used as part of a speculative doomsday struggle when much of that flora was and is witness to an ongoing genocide of Indigenous culture that seems to fall outside of the apocalyptic occurrences that Preppers alludes to?

When a point is made of adopting the vocabulary of the "local", one expects the work to question the realities of what it means to be local, especially when the work is being hosted by an institution (Fremantle Arts Centre) that posits itself as both a leading venue for contemporary art in WA and as a thriving hotspot for community art engagement.

Perhaps because of its moody aesthetic of blacks and greys, strobe lighting, metal compound and consumer militarism, Dan’s work doesn't have an answer for these kinds of questions. But to be fair, outside of Tiyan’s work, these sorts of non-answers exist all over the show. Queerness, locality, internet culture and nationalism, among other ideological hotspots, become props for that provoke and titillate.

The spectre of violence is used as an ambivalent and open-ended question, and while it feels purposeful, all it really amounts to is an in-joke that leaves those outside of the punchline to their own devices.

"Researching preppers is fucking depressing," Dan admits to me in January, almost as an aside.

We’re in a cafe near the Fremantle Arts Centre. The summer weather is typically pleasant, but I’m certain the uneasiness I feel is coming from motorcycles revving at the traffic lights rather than Fremantle Oval, or the rainbow arrangement of shipping containers sitting several hundred metres away. Nevertheless, between the Dockers and a Marcus Canning installation, exhibiting work about prepperdom in Freo makes a lot of sense.

"You see the worst of the internet... it's a lot of white, alt-right, hetero alpha males. That's... a big part of prepper culture: It's not what you want to surround yourself with."

Projecting a carbon-black sheen on customised camouflage patterns, with names that draw from both the industrial military complex and a mix of native and introduced floral patterns, Dan’s prints suggest they could easily be used in a hypothetical local conflict.

Euco Splinter. Marlock Tiger Stripe. Pommy Plane DP. Red River Biccy.

The motivation for this, in Dan's re-telling, suggests an attempt at resolving the research-life art axis: he talks about owning his first home and being part of a community, things that would make someone want to escape prepperdom’s worst impulses.

The focus of the Preppers project has evolved since 2016, and so too has Dan's interest in the patterns. From an extremely broad engagement with military design - "What I was really interested in is how these different patterns can be used for different means by different people to different aims and outcomes" - to wanting to speculate and consider possibilities – "This one [the Preppers exhibition] was very much looking at the future."

Dan's work has an admirable technical command, but nevertheless does itself few favours with its presentation. Rendering the localised military patterns within the "Compound" installation, provokes other questions though – Who are these localised designs actually for?

To be blunt: Why is native flora being used as part of a speculative doomsday struggle when much of that flora was and is witness to an ongoing genocide of Indigenous culture that seems to fall outside of the apocalyptic occurrences that Preppers alludes to?

When a point is made of adopting the vocabulary of the "local", one expects the work to question the realities of what it means to be local, especially when the work is being hosted by an institution (Fremantle Arts Centre) that posits itself as both a leading venue for contemporary art in WA and as a thriving hotspot for community art engagement.

Perhaps because of its moody aesthetic of blacks and greys, strobe lighting, metal compound and consumer militarism, Dan’s work doesn't have an answer for these kinds of questions. But to be fair, outside of Tiyan’s work, these sorts of non-answers exist all over the show. Queerness, locality, internet culture and nationalism, among other ideological hotspots, become props for that provoke and titillate.

The spectre of violence is used as an ambivalent and open-ended question, and while it feels purposeful, all it really amounts to is an in-joke that leaves those outside of the punchline to their own devices.

You find it ill-fitting to discuss the show's theoretical violence

without returning to the already real violence of our current situation: At the

time of writing, there are well over four million recorded cases, and more than

300,000 have lost their lives. There are also the

aforementioned violences of bad ecologies: Failed health care systems, flawed economic systems, untrustworthy industrial relations systems; the prejudices of racism, classism, ableism, and misogyny that exacerbate the virus and wreak havoc of their own.

Eventually, the violences of a visually striking but conceptually slight project come to matter little by comparison. Instead, remembering the remaining pleasures and responsibilities of the new reality seem more important: A new job, a new home, some new plants; memories, good and bad, of dancing and getting high with friends, illnesses that come and go. You start to form new hierarchies and ways of doing things, as technology mediates the way forward for the moment.

Your mind wanders from your deadlines, not because you don't care, but because at some point, reality does the work of debunking the show's ideas and preoccupations for you. In a time where one of the greatest expressions of social solidarity is to lock yourself in your bedroom, get stoned and listen to Cypress Hill on repeat so doctors and nurses can save lives, unpacking artworks about militaristic individualism is a non-essential service.

By the end of April, you realise you were going to have this done in the middle of February: Your reverie is hubris.

︎︎︎

Eventually, the violences of a visually striking but conceptually slight project come to matter little by comparison. Instead, remembering the remaining pleasures and responsibilities of the new reality seem more important: A new job, a new home, some new plants; memories, good and bad, of dancing and getting high with friends, illnesses that come and go. You start to form new hierarchies and ways of doing things, as technology mediates the way forward for the moment.

Your mind wanders from your deadlines, not because you don't care, but because at some point, reality does the work of debunking the show's ideas and preoccupations for you. In a time where one of the greatest expressions of social solidarity is to lock yourself in your bedroom, get stoned and listen to Cypress Hill on repeat so doctors and nurses can save lives, unpacking artworks about militaristic individualism is a non-essential service.

By the end of April, you realise you were going to have this done in the middle of February: Your reverie is hubris.

︎︎︎

^^^ images 5-9, photography by Rebecca Mansell

"The show has a weird relationship with violence: It is sort

of weirdly attracted to it but at the same time kind of repulsed," Guy

says, the gentle ambience of the building more comfortable with this statement

than the pulse of the traffic outside.

He admits that part of Preppers’ aim is to engage with the explicit thrill of violence; that by presenting it so openly the show is not letting the audience off the hook.

"That's an attraction that we're deliberately drawing attention to because that's one of the things that's most difficult about preppers, they're attracted to violence.”

However, he admits his own understandings, once animated by the political promise that violence can offer, have evolved throughout his extended engagement.

"One of my reference points has been that Mao quote – 'There is chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent' – that disaster is an opportunity to change,” he explains.

“That was how I initially approached the show, but the project, as the politics has shifted over the past, almost four years, so my attitudes towards this has changed, definitely mine has.

"When you're 22, it's easy to advocate that people should get hurt for a greater good, but when you're 30 you're like, 'Oh that might be people I know and like.'"

This reflectiveness is also apparent in how he considers the show’s stance towards its prepperdom’s relationship with violence.

"I wondered whether the show should have taken a strong position towards prepping, but for me ambivalence is just sort of common sense?" he ponders, before arriving at a more confident position.

"I find ambivalence to be really powerful because it has the sense that we can't extricate ourselves from responsibility. The interesting thing about our show's relationship with violence and political ambivalence is that it's saying is that we are part of this.

"To me, it would feel naive to pass obvious judgement or wash the violence from the show.”

He admits that part of Preppers’ aim is to engage with the explicit thrill of violence; that by presenting it so openly the show is not letting the audience off the hook.

"That's an attraction that we're deliberately drawing attention to because that's one of the things that's most difficult about preppers, they're attracted to violence.”

However, he admits his own understandings, once animated by the political promise that violence can offer, have evolved throughout his extended engagement.

"One of my reference points has been that Mao quote – 'There is chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent' – that disaster is an opportunity to change,” he explains.

“That was how I initially approached the show, but the project, as the politics has shifted over the past, almost four years, so my attitudes towards this has changed, definitely mine has.

"When you're 22, it's easy to advocate that people should get hurt for a greater good, but when you're 30 you're like, 'Oh that might be people I know and like.'"

This reflectiveness is also apparent in how he considers the show’s stance towards its prepperdom’s relationship with violence.

"I wondered whether the show should have taken a strong position towards prepping, but for me ambivalence is just sort of common sense?" he ponders, before arriving at a more confident position.

"I find ambivalence to be really powerful because it has the sense that we can't extricate ourselves from responsibility. The interesting thing about our show's relationship with violence and political ambivalence is that it's saying is that we are part of this.

"To me, it would feel naive to pass obvious judgement or wash the violence from the show.”

It is easy to see why there is the perception this show is

"fascist," but I think that response is off the mark. Part of this is

a problem that needs to be acknowledged when reviewing a show that is debated

and discussed by a tight-knit artistic community: Within a narrow structure of

hierarchies, politics and gossiping, it's sometimes difficult to know where

genuine analysis ends and other biases enter the picture.

The criticism instead conceals a more complicated truth. While the show's curators together have a full and varied understanding of what it is to be a self-sufficient survivalist, their own works are mostly interested in aesthetic and philosophical extremes: Violence, individualism, systemic failure, masculinity, bravado and nationalism, among others. It's difficult to pretend this is anything other than a show about the darkest aspects of prepperdom when – other than Tiyan’s work – that is what is presented as its primary point of concern.

Furthermore, whenever you choose to spend time with something, you inevitably impart a legitimacy towards that subject. The ambivalence that Guy speaks of forms a totalising ambience. We spend so much time with one particular approach it is difficult to understand prepperdom on anything but the terms that the core artists in this show ascribe to it. And if you ascribe a pathological, militarised interest in violence as a key preoccupation in your work, it's inevitable that some people will call it fascist.

It’s also an ahistorical perspective: At many points in history, people have laid it on the line - both rightly and wrongly - for something they believe in or are opposed to. But because the show is largely fixated on a single note of horror and titillation, viewers only occasionally glimpse the framework that violence sits within and are otherwise left to fill those gaps with their imagination.

Whether it's Guy’s “The Ant and the Grasshopper” video, Loren’s polygraphs and bows, or the sleek militarism of Dan’s strobe lights, one is repetitively reminded that destruction wreaks havoc, but that destruction is exciting.

In reality though, even nihilism is usually rooted in precedent.

The criticism instead conceals a more complicated truth. While the show's curators together have a full and varied understanding of what it is to be a self-sufficient survivalist, their own works are mostly interested in aesthetic and philosophical extremes: Violence, individualism, systemic failure, masculinity, bravado and nationalism, among others. It's difficult to pretend this is anything other than a show about the darkest aspects of prepperdom when – other than Tiyan’s work – that is what is presented as its primary point of concern.

Furthermore, whenever you choose to spend time with something, you inevitably impart a legitimacy towards that subject. The ambivalence that Guy speaks of forms a totalising ambience. We spend so much time with one particular approach it is difficult to understand prepperdom on anything but the terms that the core artists in this show ascribe to it. And if you ascribe a pathological, militarised interest in violence as a key preoccupation in your work, it's inevitable that some people will call it fascist.

It’s also an ahistorical perspective: At many points in history, people have laid it on the line - both rightly and wrongly - for something they believe in or are opposed to. But because the show is largely fixated on a single note of horror and titillation, viewers only occasionally glimpse the framework that violence sits within and are otherwise left to fill those gaps with their imagination.

Whether it's Guy’s “The Ant and the Grasshopper” video, Loren’s polygraphs and bows, or the sleek militarism of Dan’s strobe lights, one is repetitively reminded that destruction wreaks havoc, but that destruction is exciting.

In reality though, even nihilism is usually rooted in precedent.

At a certain point, you will realise that none of this actually

matters, and that is precisely why it matters more than ever. Fucking around

for a few months on a review with an endlessly shifting end date feels only

partially attuned to the ways and whims of whatever is going on outside.

It feels like others are the same: Stream after stream, feed after feed, app after app of artistic or arts-adjacent labour that forms an echo chamber of content. Culture, identity and politics sit only dozens of pixels apart on a monitor. When there was already a sense of exhaustion about the digital realm, time now feels endless, a groundhog day.

There are real and valid concerns about what we hope will be a temporary paradigm – at a certain point artists will need to be compensated for their labour. As Shawn Reynaldo and Lara Chapman respectively suggest: Consideration should be paid to the appropriation of physical art practices into online spaces which they are scarcely suited to functioning within, as well as the possibility practitioners who have worked for years in this space will suddenly be chased out by people who don’t understand how the internet works.

However, despite the overwhelming risk of fatigue, where ideas of play scan as a cynical novelty in this post-Google world, some people are playing with a collective and ongoing sense of solidarity and commitment: The work of radio stations such as Pretend, Bus and Skylab in Melbourne, or Sydney art engagements like Prototype or Running Dog, is especially pertinent, with some of these organisations fundraising for musicians or working in concert with larger institutions. British dance music institution R&S’ efforts in support of the NHS also come to mind.

The flattening of our social lives into online performances means that this work shares space with projects like Emma Buswell's knitted wonders (cool), and more generally, people's sourdoughs and cooking (the wellness industrial complex will never be cool), or people’s rankings of Terminator films. In some ways, this mirrors the sense of community depicted in Tiyan’s work, where social media is used to construct an enthusiastic and shared point of interest.

You wonder if these expressions of care in a necessarily boring time could form the beginnings of something else. That this sudden pause is not “nature healing”, but instead a chance to stop and look at the roads we are heading down.

As a whole Preppers resists this collectivity, and is only community minded in the same way as a blockbuster sci-fi apocalyptic thriller, in that it is designed for lots of people to look at it. While the exhibition is shiny, slick and covers a lot of ground within limited parameters, it fails to sufficiently articulate a complex understanding of the historical baggage that is attached to its subject.

The show is obtuse as to how or why it chooses to engage with this subculture. It uses ambiguity and ambivalence as tools to play and tease out the disturbing thrill of violence, while remaining tantalisingly remote from it. The show's key artists/curators argue convincingly that there's a role for ambiguity and nuance in presenting these issues, but Preppers failure lies in its inability to get its hands dirty, to deconstruct the community it embeds itself with.

It’s a show that reactively engages with the politics of representing its subject - a necessary, if restrictive goal - and what it looks like; as opposed to constructing an understanding of how that subject interacts with and forecasts a sense of possibility to the world.

It feels like others are the same: Stream after stream, feed after feed, app after app of artistic or arts-adjacent labour that forms an echo chamber of content. Culture, identity and politics sit only dozens of pixels apart on a monitor. When there was already a sense of exhaustion about the digital realm, time now feels endless, a groundhog day.

There are real and valid concerns about what we hope will be a temporary paradigm – at a certain point artists will need to be compensated for their labour. As Shawn Reynaldo and Lara Chapman respectively suggest: Consideration should be paid to the appropriation of physical art practices into online spaces which they are scarcely suited to functioning within, as well as the possibility practitioners who have worked for years in this space will suddenly be chased out by people who don’t understand how the internet works.

However, despite the overwhelming risk of fatigue, where ideas of play scan as a cynical novelty in this post-Google world, some people are playing with a collective and ongoing sense of solidarity and commitment: The work of radio stations such as Pretend, Bus and Skylab in Melbourne, or Sydney art engagements like Prototype or Running Dog, is especially pertinent, with some of these organisations fundraising for musicians or working in concert with larger institutions. British dance music institution R&S’ efforts in support of the NHS also come to mind.

The flattening of our social lives into online performances means that this work shares space with projects like Emma Buswell's knitted wonders (cool), and more generally, people's sourdoughs and cooking (the wellness industrial complex will never be cool), or people’s rankings of Terminator films. In some ways, this mirrors the sense of community depicted in Tiyan’s work, where social media is used to construct an enthusiastic and shared point of interest.

You wonder if these expressions of care in a necessarily boring time could form the beginnings of something else. That this sudden pause is not “nature healing”, but instead a chance to stop and look at the roads we are heading down.

As a whole Preppers resists this collectivity, and is only community minded in the same way as a blockbuster sci-fi apocalyptic thriller, in that it is designed for lots of people to look at it. While the exhibition is shiny, slick and covers a lot of ground within limited parameters, it fails to sufficiently articulate a complex understanding of the historical baggage that is attached to its subject.

The show is obtuse as to how or why it chooses to engage with this subculture. It uses ambiguity and ambivalence as tools to play and tease out the disturbing thrill of violence, while remaining tantalisingly remote from it. The show's key artists/curators argue convincingly that there's a role for ambiguity and nuance in presenting these issues, but Preppers failure lies in its inability to get its hands dirty, to deconstruct the community it embeds itself with.

It’s a show that reactively engages with the politics of representing its subject - a necessary, if restrictive goal - and what it looks like; as opposed to constructing an understanding of how that subject interacts with and forecasts a sense of possibility to the world.

I walked out of the exhibition with a feeling of distance from my

community, from my duties and responsibilities. If we live in a society, I was

left perplexed at the point of it all. If all I knew of survival was gleaned from this

exhibition, I’d be left wondering how I could avoid the then unknown, presently

banal horror of the situation we now find ourselves in.

Furthermore, I was also reminded of Sarah Michelle Gellar's Krysta Now in Richard Kelly's 2005 satirical sci-fi cult film Southland Tales: "Scientists are saying the future is going to be far more futuristic than they originally predicted," she says, delivering the line with knowing irony for a character that reproduces knowledge in a search for cultural authority.

Preppers runs on a similar confidence. Perhaps in a world where the cultural and political intermingle without any emancipatory goal beyond granting the mildest of omniscience regarding the levels of "cooked" that are used to describe news events in group chats, this ambivalence is potent enough for some. It isn't for me.

Though it is funny, right now, to look back at the level of consternation this show caused. If physical exhibitions were possible right now, would the issues people had even register? Would Preppers’ methods of engagement offer us something in this time of unrest? Would this iteration of the exhibition show a greater interest in exploring how the past and present facilitate tomorrow?

Instead, maybe it is better to leave the fantasies of an unknown future behind, to go forth and activate other possibilities: Look after your plants, read that book, watch that movie, make that sourdough. While speculation has its value, it feels like it is time to take a stake in the kind of the world that we want to live in.

A friend posts something about the drawing down of superannuation on Instagram and we converse about how cooked the whole thing is. They casually mention to me that the world is going to end.

"To be honest, the apocalypse is probably just going to be a series of subtle changes that render everything we knew unknowable," I say.

Like the exhibition, it's the kind of flourish that sounds impressive but rings hollow; they don't reply.

When I finish this article, I feel a song coming on. I listen to that and think about what I will do next.

Furthermore, I was also reminded of Sarah Michelle Gellar's Krysta Now in Richard Kelly's 2005 satirical sci-fi cult film Southland Tales: "Scientists are saying the future is going to be far more futuristic than they originally predicted," she says, delivering the line with knowing irony for a character that reproduces knowledge in a search for cultural authority.

Preppers runs on a similar confidence. Perhaps in a world where the cultural and political intermingle without any emancipatory goal beyond granting the mildest of omniscience regarding the levels of "cooked" that are used to describe news events in group chats, this ambivalence is potent enough for some. It isn't for me.

Though it is funny, right now, to look back at the level of consternation this show caused. If physical exhibitions were possible right now, would the issues people had even register? Would Preppers’ methods of engagement offer us something in this time of unrest? Would this iteration of the exhibition show a greater interest in exploring how the past and present facilitate tomorrow?

Instead, maybe it is better to leave the fantasies of an unknown future behind, to go forth and activate other possibilities: Look after your plants, read that book, watch that movie, make that sourdough. While speculation has its value, it feels like it is time to take a stake in the kind of the world that we want to live in.

A friend posts something about the drawing down of superannuation on Instagram and we converse about how cooked the whole thing is. They casually mention to me that the world is going to end.

"To be honest, the apocalypse is probably just going to be a series of subtle changes that render everything we knew unknowable," I say.

Like the exhibition, it's the kind of flourish that sounds impressive but rings hollow; they don't reply.

When I finish this article, I feel a song coming on. I listen to that and think about what I will do next.

PREPPERS

Tiyan Baker, Guy Louden, Loren Kronemyer, Dan McCabe & Thomas Yeomans

Fremantle Arts Centre

16 November 2019 - 27 January 2020

Ben Rodin would like to thank Dan, Guy, Loren and Tiyan for their openness and willingness to be interviewed for this review, their insights were greatly appreciated.

Image credits:

All Photos by Rebecca Mansell, courtesy of Fremantle Arts Centre and the artists.

1. Guy Louden, Dan McCabe, Loren Kronemyer, E.O.T.W.A.W.K.I., 2019, digital video, screen capture, found media.

2. Loren Kronemyer, Training for True Aim, 2019, lie detector, compound bow, targets, hay bales, accessories.

3. Tiyan Baker, Bamboo Paradise, 2019, digital video, bamboo, sisal rope, potted plants, some video footage provided by Survival Builder.

4. Loren Kronemyer, Feather Spear Trap, 2018, PVC, saw blades, rope, diamond ring.

5. Loren Kronemyer, Wounded Amazon of the Capitalocene 2, 2019, arrow shafts, custom broadheads, fletchings, serving.

6. Dan McCabe, Compound, 2019, industrial enamel, steel, motion sensors and LED flood lights. Dan McCabe, Red River Biccy, 2019, automotive carbon fibre vinyl on acrylic, stainless steel and “gun blued” steel. Guy Louden, The Ant and the Grasshopper, 2019, 2-channel digital video, looped. Guy Louden, Ark (II), 2019, Wikipedia backup, custom computer, gold leaf, hard case, custom fabric, rolling plinth.

7 & 8. Loren Kronemyer, Wounded Amazon of the Capitalocene 2, 2019, arrow shafts, custom broadheads, fletchings, serving. Guy Louden, Capriccio 1-3, 2017 giclee print from digital render. Dan McCabe, Compound, 2019, industrial enamel, steel, motion sensors and LED flood lights. Dan McCabe, Red River Biccy, 2019, automotive carbon fibre vinyl on acrylic, stainless steel and “gun blued” steel. Guy Louden, Ark (II), 2019, Wikipedia backup, custom computer, gold leaf, hard case, custom fabric, rolling plinth.

9. Guy Louden, Dan McCabe, Loren Kronemyer, E-waste Barricade, 2019, e-waste, steel, zipties.

16 November 2019 - 27 January 2020

Ben Rodin would like to thank Dan, Guy, Loren and Tiyan for their openness and willingness to be interviewed for this review, their insights were greatly appreciated.

Image credits:

All Photos by Rebecca Mansell, courtesy of Fremantle Arts Centre and the artists.

1. Guy Louden, Dan McCabe, Loren Kronemyer, E.O.T.W.A.W.K.I., 2019, digital video, screen capture, found media.

2. Loren Kronemyer, Training for True Aim, 2019, lie detector, compound bow, targets, hay bales, accessories.

3. Tiyan Baker, Bamboo Paradise, 2019, digital video, bamboo, sisal rope, potted plants, some video footage provided by Survival Builder.

4. Loren Kronemyer, Feather Spear Trap, 2018, PVC, saw blades, rope, diamond ring.

5. Loren Kronemyer, Wounded Amazon of the Capitalocene 2, 2019, arrow shafts, custom broadheads, fletchings, serving.

6. Dan McCabe, Compound, 2019, industrial enamel, steel, motion sensors and LED flood lights. Dan McCabe, Red River Biccy, 2019, automotive carbon fibre vinyl on acrylic, stainless steel and “gun blued” steel. Guy Louden, The Ant and the Grasshopper, 2019, 2-channel digital video, looped. Guy Louden, Ark (II), 2019, Wikipedia backup, custom computer, gold leaf, hard case, custom fabric, rolling plinth.

7 & 8. Loren Kronemyer, Wounded Amazon of the Capitalocene 2, 2019, arrow shafts, custom broadheads, fletchings, serving. Guy Louden, Capriccio 1-3, 2017 giclee print from digital render. Dan McCabe, Compound, 2019, industrial enamel, steel, motion sensors and LED flood lights. Dan McCabe, Red River Biccy, 2019, automotive carbon fibre vinyl on acrylic, stainless steel and “gun blued” steel. Guy Louden, Ark (II), 2019, Wikipedia backup, custom computer, gold leaf, hard case, custom fabric, rolling plinth.

9. Guy Louden, Dan McCabe, Loren Kronemyer, E-waste Barricade, 2019, e-waste, steel, zipties.