Don’t Stare at the Sun / for Too Long![]()

23 February 2020Anna Dunnill on Amy Perejuan-Capone

Pakenham Street Art Space, ARTSOURCE Old Customs House

Amy Perejuan-Capone built an aeroplane with her dad.

In Don’t Stare at the Sun / for Too Long, Amy’s December 2019 exhibition at PSAS, The Plane (dreamer), 2019, is monumental even in the vast space. It is a 1:1 replica of a light aircraft belonging to Amy's father Greg Perejuan, a long-time flying enthusiast; they worked on it over a year and a half.

In the two-channel video Legacy II, 2019, two planes—Amy’s plane and her dad’s plane—run along the ground side by side, two sets of identical wheels in the dirt.

In Don’t Stare at the Sun / for Too Long, Amy’s December 2019 exhibition at PSAS, The Plane (dreamer), 2019, is monumental even in the vast space. It is a 1:1 replica of a light aircraft belonging to Amy's father Greg Perejuan, a long-time flying enthusiast; they worked on it over a year and a half.

In the two-channel video Legacy II, 2019, two planes—Amy’s plane and her dad’s plane—run along the ground side by side, two sets of identical wheels in the dirt.

Then one set of wheels lifts off the ground, leaving the other trundling along the runway. As the video progresses we can see that it’s being pulled along by Amy, like a wheeled toy on a string, except huge. I can’t help but think of these two crafts as being parent and child: the one is built in the image of the other, but unformed, or still forming.

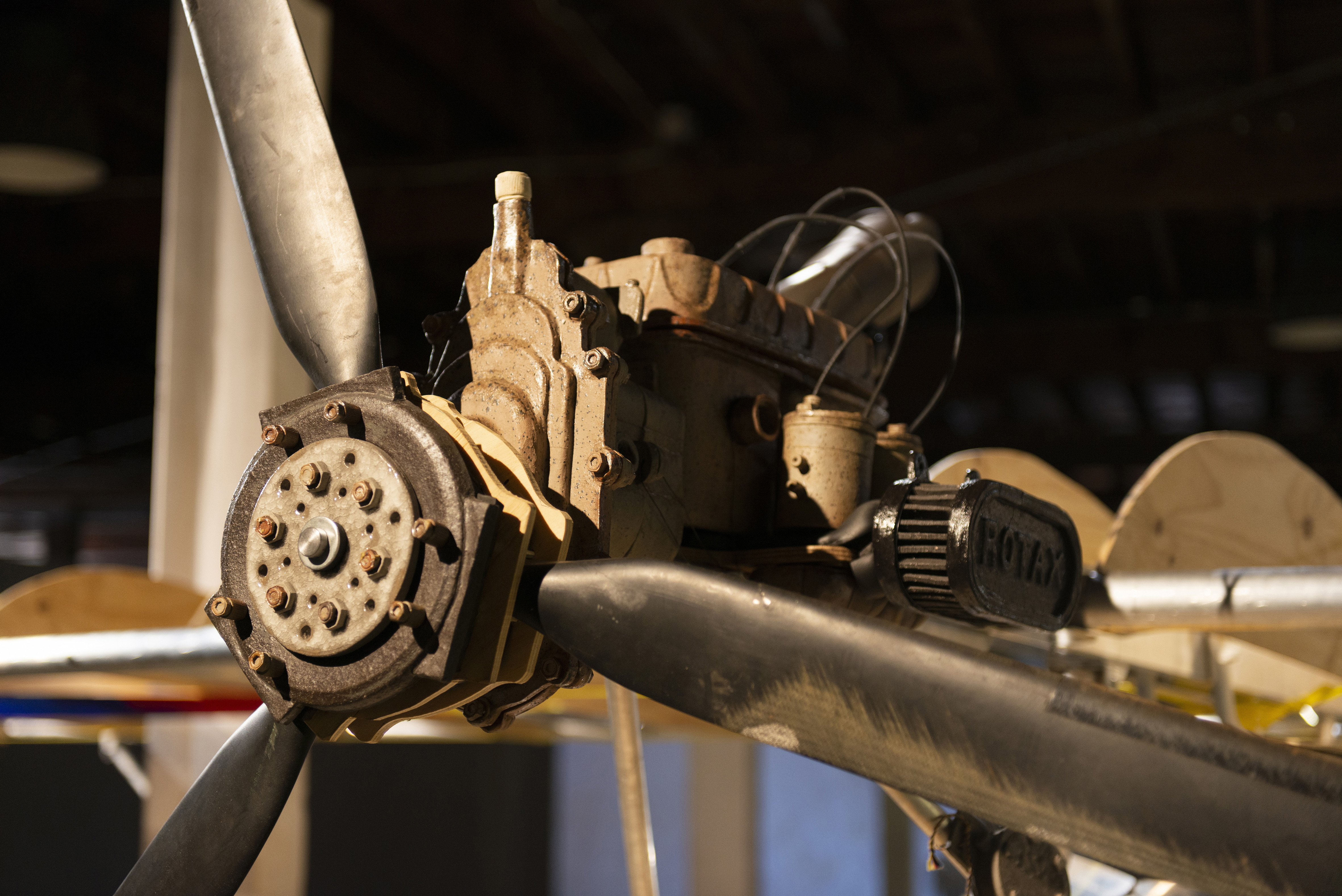

Amy’s plane cannot fly—not yet, anyway. While its wheels and wooden skeleton look (to my untrained eye) fairly plausible, many of the interior components are made from hand-built stoneware, chunky and non-functional.

Amy’s plane cannot fly—not yet, anyway. While its wheels and wooden skeleton look (to my untrained eye) fairly plausible, many of the interior components are made from hand-built stoneware, chunky and non-functional.

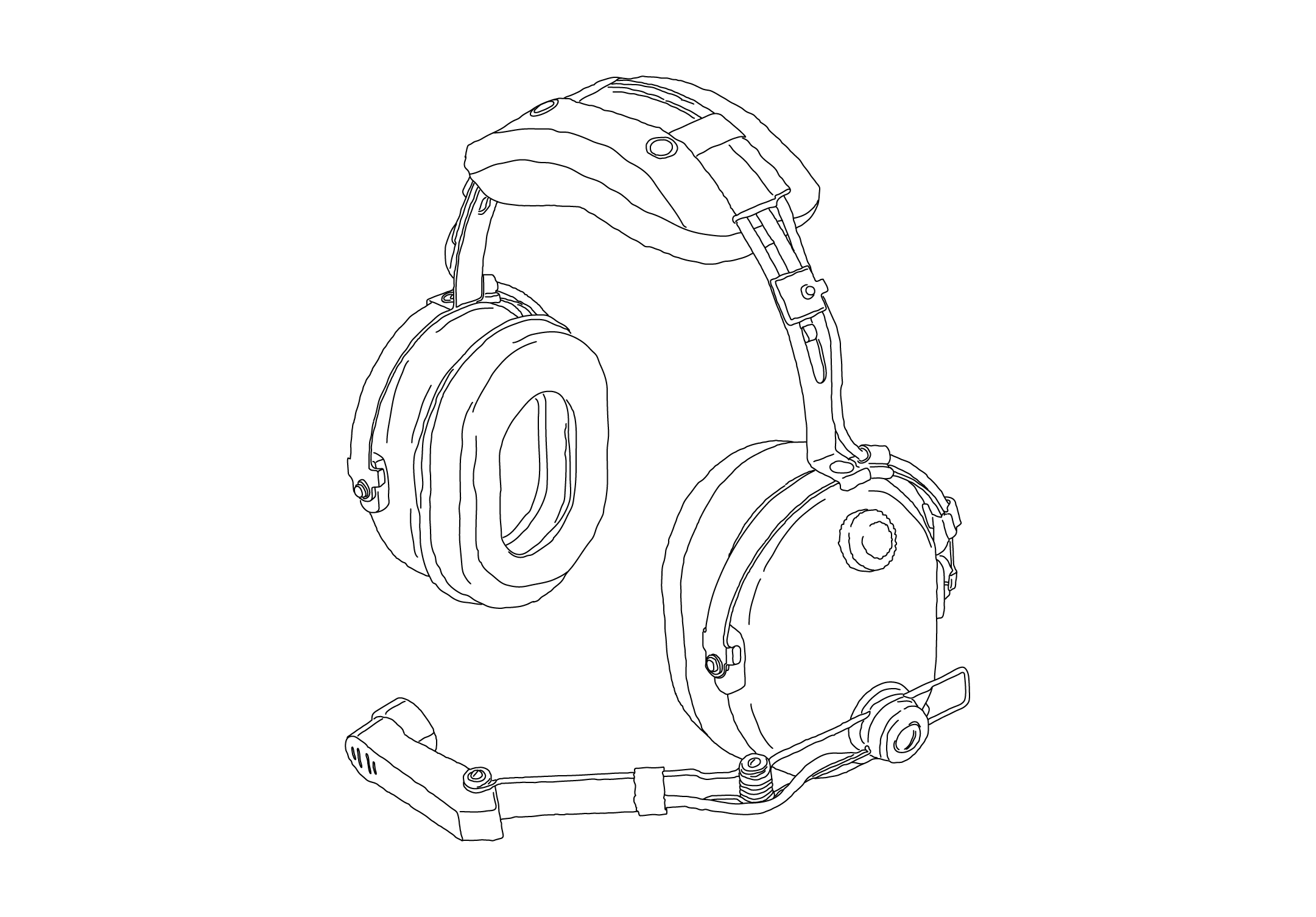

Two headsets rest on the cockpit seats, awaiting a pilot and co-pilot, but somewhat poignantly these clay objects cannot speak to one another. If the plane is a physical articulation of passed-down knowledge and an embrace of family lineage, the ceramic components represent gaps that inevitably occur: static, feedback, things improperly transmitted or received. According to the catalogue essay, though, the plane is an ongoing project, the stand-in parts to be gradually swapped out for functioning ones until it too can rise up off the ground. (It also flat-packs, Amy tells me, a detail I appreciate.)

[continue reading below︎]

^^^ From top: Don’t Stare at the Sun/ For too Long - installation view. Photo by Amy Perejuan-Capone;

The Plane (dreamer) - engine detail, 2019, mixed media. Photo by Rojer DSouza;

The Plane (dreamer) - cockpit detail, 2019, mixed media. Photo by Rojer DSouza;

Skins, 2019, emergency blanket foil. Photo by Amy Perejuan-Capone.

The Plane (dreamer) - engine detail, 2019, mixed media. Photo by Rojer DSouza;

The Plane (dreamer) - cockpit detail, 2019, mixed media. Photo by Rojer DSouza;

Skins, 2019, emergency blanket foil. Photo by Amy Perejuan-Capone.

In videos, the plane’s wings are clad in emergency blankets that glint in the sunlight. In the gallery this gold covering—the skin—is stretched out on the wall, a protective wrap that holds the possibility of warmth.

I live in Melbourne now, but I caught the last day of Don’t stare at the sun / for too long while visiting Perth for Christmas. I was staying with my parents. My dad hasn’t been well the last couple of years; my mum, a school principal who is sharp and capable and professionally whip-smart, has now mostly stopped working to care for him. The feeling of things slipping away—knowledge, connection—has never felt more real.

In the video Legacy I, 2019, we have the plane’s-eye view as the original aircraft flies over a landscape etched with fingerprint whorls, an aerial spread of grain fields and rusty dirt. It casts a perfect plane-shaped shadow as though this one is now the toy, a model dangling from the ceiling. At one point, the airborne plane—the parent plane—passes above its glittering earthbound progeny, the shadow perfectly matched in size.

I live in Melbourne now, but I caught the last day of Don’t stare at the sun / for too long while visiting Perth for Christmas. I was staying with my parents. My dad hasn’t been well the last couple of years; my mum, a school principal who is sharp and capable and professionally whip-smart, has now mostly stopped working to care for him. The feeling of things slipping away—knowledge, connection—has never felt more real.

In the video Legacy I, 2019, we have the plane’s-eye view as the original aircraft flies over a landscape etched with fingerprint whorls, an aerial spread of grain fields and rusty dirt. It casts a perfect plane-shaped shadow as though this one is now the toy, a model dangling from the ceiling. At one point, the airborne plane—the parent plane—passes above its glittering earthbound progeny, the shadow perfectly matched in size.

Don’t stare at the sun / for too long. A piece of sage advice tempered with pragmatism. (How long until I should stop staring?) It’s a reference of course to Icarus, who dreamed of flight but, in his glee at defying the gods, flew too close to the sun and found himself tumbling back to earth, shoulders caked with molten wax.

This summer though the phrase takes on a different meaning. Over and over, that weird red sun slides through my Instagram feed, from friends in Sydney, Canberra, along the south coast. It looks alien at first, frightening, but quickly settles into being normal, like automatically checking the AirWatch website when I wake up to see if the air is hazardous or not. One morning in Melbourne the sun is a red disc and it’s almost comforting: oh, it’s here now too. I try to take a photo of it rising above the power lines but it doesn’t really translate to the phone screen; you had to be there, smelling the smoke, feeling your throat dry and scratchy.

This summer though the phrase takes on a different meaning. Over and over, that weird red sun slides through my Instagram feed, from friends in Sydney, Canberra, along the south coast. It looks alien at first, frightening, but quickly settles into being normal, like automatically checking the AirWatch website when I wake up to see if the air is hazardous or not. One morning in Melbourne the sun is a red disc and it’s almost comforting: oh, it’s here now too. I try to take a photo of it rising above the power lines but it doesn’t really translate to the phone screen; you had to be there, smelling the smoke, feeling your throat dry and scratchy.

[continue reading ︎]

^^^ From top: Site specific architectural intervention, 2018, pink theatre gels on existing lighting, artificial snow, industrial fan;

Every step is moving me up, 2018, aluminium, parachute, industrial fan;

This is how we walk on the moon, 2018, single channel video on mini CTV;

One moment there, 2018, three channel video, paper mâché, bamboo, steel.

All images by Amy Perejuan-Capone.

Every step is moving me up, 2018, aluminium, parachute, industrial fan;

This is how we walk on the moon, 2018, single channel video on mini CTV;

One moment there, 2018, three channel video, paper mâché, bamboo, steel.

All images by Amy Perejuan-Capone.

In July 2018 I saw Amy’s previous solo exhibition, This is How We Walk on the Moon, at Artsource Old Customs House. I was in Perth visiting my parents again, one of five visits that year, ten flights back and forth across the Nullabor. This exhibition was made on residency in Svalbard, the northernmost permanently-settled location on the globe. It drew on both the history of grueling Arctic exploration, the glowing geodesic permaculture dome, and the Svalbard seed-bank—a hope for the future that feels both increasingly urgent and precarious. It takes in a landscape very different to the wheatbelt fields viewed from the air, icy and forbidding but just as lonely.

Amy’s residency took place in the dead of Arctic winter. I remember she posted a video on social media of the whole community gathered together outside, shadowy figures wrapped up against the bitter cold, watching for the moment when—after months of darkness—the sun’s first gleam illuminated the horizon. A pinprick of light pierced the skyline, flashing across the flat landscape, and the crowd erupted into whoops and howls of joy. The sun. The sun has returned.

Amy’s residency took place in the dead of Arctic winter. I remember she posted a video on social media of the whole community gathered together outside, shadowy figures wrapped up against the bitter cold, watching for the moment when—after months of darkness—the sun’s first gleam illuminated the horizon. A pinprick of light pierced the skyline, flashing across the flat landscape, and the crowd erupted into whoops and howls of joy. The sun. The sun has returned.

For thousands of years these rituals, these cycles, have occurred. Moon, earth, sun, three spheres in orbit, tumbling in a black void, their movements dictating seasons, foods, living places, dreams and ceremonies. The vast majority of Australians—nearly 90 percent—now live in cities; the cycles of nature don’t affect our lives much unless the aircon stops working. But this summer the eastern cities are turning back into wild places. The air is thick with bushfire smoke; the sky lets loose hailstones and floods in midsummer. Twice in recent weeks, a rainstorm crossed paths with a dust-storm that had whipped up the topsoil in drought-parched northern Victoria. The downpour of ‘mud rain’ painted Melbourne’s streets and buildings the same rust colour as the fields Amy's little gold plane trundles through. (The Yarra, it was reported by the ABC, was ‘browner than usual.’)

An Indigenous radio host on Melbourne’s 3CR tells the bloke he’s interviewing, an Elder from the Mallee, ‘Your Country’s been dumped all over us this week.’ The sun is back to yellow though, in the sky and on Instagram, for now.

Amy’s two successive projects meditate on vast distances, on isolation, on human frailty and the struggle for the impossible. Her work also wrestles with the consequences of ‘progress’, the radically-altered landscapes that follow inevitably in the wake of human achievement. Heroic quests and feats of endurance are tangled up with the complex links of family. How can we reach each other? How to walk on this earth? The seeds are safe for the moment; the plane trundles along a dirt track towards potential flight. The spheres continue to orbit. We press on.

Amy’s two successive projects meditate on vast distances, on isolation, on human frailty and the struggle for the impossible. Her work also wrestles with the consequences of ‘progress’, the radically-altered landscapes that follow inevitably in the wake of human achievement. Heroic quests and feats of endurance are tangled up with the complex links of family. How can we reach each other? How to walk on this earth? The seeds are safe for the moment; the plane trundles along a dirt track towards potential flight. The spheres continue to orbit. We press on.

^^^

Legacy I - still, 2019, single channel video. Courtesy of Amy Perejuan-Capone.

^^^

Legacy I - still, 2019, single channel video. Courtesy of Amy Perejuan-Capone.Don’t Stare at the Sun/ for Too Long

Amy Perejuan-Capone

Pakenham Street Art Space

30 November - 19 December, 2019

This Is How We Walk On The Moon

Amy Perejuan-Capone

ARTSOURCE Old Customs House

15 - 29 July, 2018