COMMUNITY, Faces of the

21 June 2020

Obituaries for Faces of the Community by Ellen Broadhurst, Jack Caddy & Grace Connors, Karl Halliday, Brent Harrison, Shannon Lyons, Harry Price, Jaxon Waterhouse and Gemma Weston.

Sign Post

The “faces” were a sign post on the way back from trips down south during the school holidays. It was a welcome reminder that we weren’t too far away from home as the traffic slowly crawled past Cockburn Central and I squirmed in the backseat busting to pee.

— Brent Harrison

Taxpayers Wanted a Clock

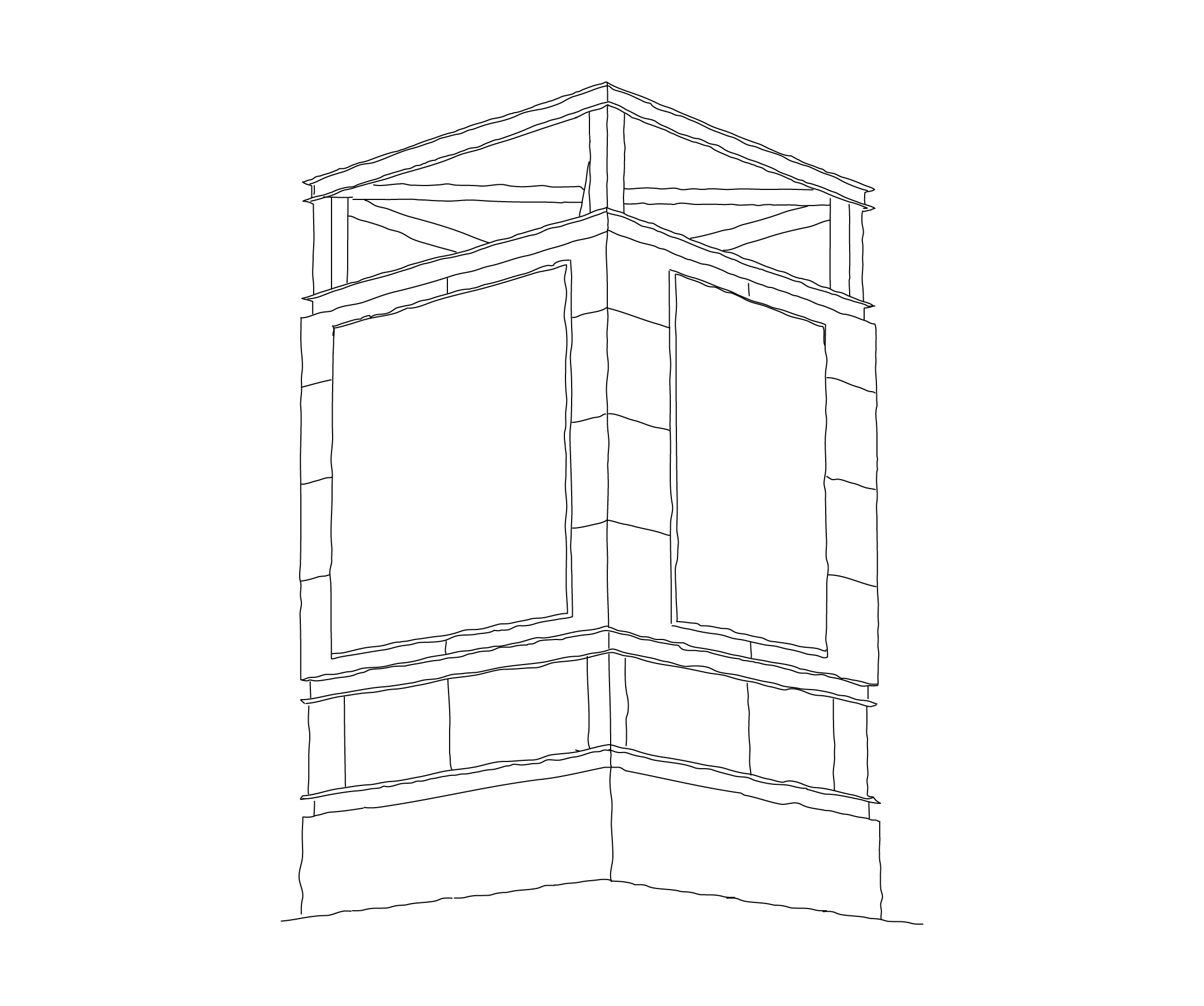

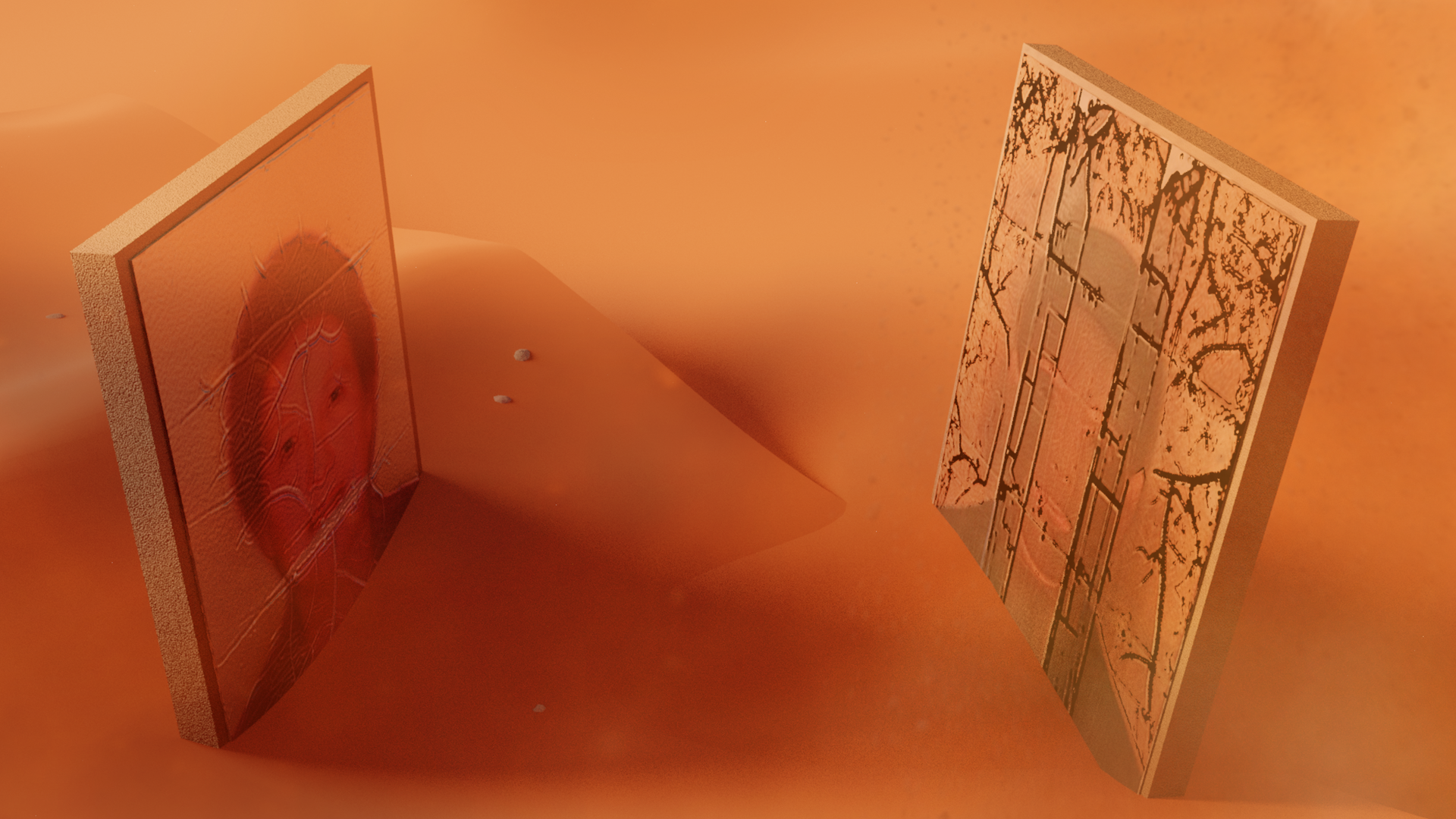

Dying before the year [?]1 Twin objects are found. Naked and laid bare for time to consume. Two monolithic, rectangular planes finally greet each other, bouncing light back and forth between their metal faces. The world’s longest staring competition. A dynamic conversation of heat, of blistering and bubbling and pulsing and peeling. Revealing weathered subsurfaces from the flayed vinyl that litters their rooted heels. A plastic film strata, an anti-mulch. A laminate barrier in and towards themselves, left to be reclaimed by the land they were meant to represent.

A once progressive digital synthesis that generated two faces. Two faces who’s physiognomic traits were blended into a harmonious hole, which later became prey to a contentious public humiliation. A flash mob marriage of two quarreling objects removed due to public dismay. Deaccessioned and carelessly discarded.

The faces pass through each other in their locked, eternal embrace. As space, and time folds into itself.

Cursed to always remain the same, deteriorating public artworks become cultural artifacts, fucked over by time, and the goddamn sun. Where the carrion and mice are lovers.

A voice announces itself from nowhere that the next train to Cockburn will be arriving in 4 minutes. You have no idea what that means, you check your pockets for coins anyway. Even though currency means nothing to you.

— Grace Connors & Jack Caddy

1 The year of death signified in the [?] is a potentially unknown

variable, which we have attempted to extrapolate through a simple equation 3.08370044 × 10-9. This equation is tethered to a particular moment in time, (2006) which is the moment that the work Faces of the Community by Rodney Glick and Marco Macron, were installed at Cockburn Train Station. At the time of writing this article (May 2020) we flag an ongoing, fourteen (14) year public debate around the mystery of these works. Now, if we consider that the earth is some 4.54 billion years old, then we may have the pleasure to divide those fateful fourteen years by this almost unfathomable distance between the beginning of time and now (the time of writing this). These fourteen (14) years or 3.08370044 × 10-9 in relation to the beginning of time are of grave importance, and as we argue above, have the potential to change the course of history as we know it, even if taxpayers simply wanted a clock in place of the Faces of the Community.

![]()

Image credit: Jack Caddy, Time waits for no one, 2020, Digital Image, Dimensions Variable. Coutesy of the artist.

A Beautiful Lie

I never bought into the technical processes the artists professed to have used to create Faces of the Community (2006). Neither did I believe that any consultation or collaboration (?) with community members actually occurred. Instead, I always imagined that the angelic faces flanking the Kwinana were softly blurred passport photographs of Marco's Italian mother and nephew*. I've built the work up in my mind to be a beautiful artists' lie.

*I don't know if Marco even has a nephew.

— Shannon Lyons

Let Me Google That For You

I remember weighing into the discussion on the “remove the Cockburn train station faces” Facebook group c2012, replying to posts questioning what the photos were by typing “what do the faces at Cockburn Station mean’ into LMGTFY.com & posting the link. I felt sanctimonious, and

Image credit: Jack Caddy, Time waits for no one, 2020, Digital Image, Dimensions Variable. Coutesy of the artist.

A Beautiful Lie

I never bought into the technical processes the artists professed to have used to create Faces of the Community (2006). Neither did I believe that any consultation or collaboration (?) with community members actually occurred. Instead, I always imagined that the angelic faces flanking the Kwinana were softly blurred passport photographs of Marco's Italian mother and nephew*. I've built the work up in my mind to be a beautiful artists' lie.

*I don't know if Marco even has a nephew.

— Shannon Lyons

Let Me Google That For You

I remember weighing into the discussion on the “remove the Cockburn train station faces” Facebook group c2012, replying to posts questioning what the photos were by typing “what do the faces at Cockburn Station mean’ into LMGTFY.com & posting the link. I felt sanctimonious, and

invested. Marco Marcon had been my honors tutor and my first ever paid arts job was minding Rodney Glik’s God Favoured at Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, an exhibition that featured sculptures of several of my friends. Recently the group came alive with posts solving, yet again. the endlessly forgotten mystery of who the faces were.

I only visited the work ‘on location’ just before it was removed, and by accident. A South West Coastlines bus cracked its windscreen and we passengers were driven to Cockburn station to wait for a new one. From memory it wasn’t possible to read the interpretative panel and see the photographs at the same time; the faces were most visible from the freeway, at 100km/hr on the way to and from somewhere else. Perhaps you could see them from the train platform, which seems to have become operational in 2007, a year after the photos were installed above it, and a year in which I shared 2GB of data per month between four people and reflexively googled nothing. The bus arrived before I could check. Curiosity can be dependant on a lot of resources, time included.

— Gemma Weston

![]()

Lost

I always thought they were missing persons, some rumour I’d heard somewhere. They’d impassively watch us beetle up the freeway and we’d grow uncomfortable under their stare and the visibility of it. The missing person thing seemed believable because there was something in these images that suggested they were missing – something unquantifiable shared

I only visited the work ‘on location’ just before it was removed, and by accident. A South West Coastlines bus cracked its windscreen and we passengers were driven to Cockburn station to wait for a new one. From memory it wasn’t possible to read the interpretative panel and see the photographs at the same time; the faces were most visible from the freeway, at 100km/hr on the way to and from somewhere else. Perhaps you could see them from the train platform, which seems to have become operational in 2007, a year after the photos were installed above it, and a year in which I shared 2GB of data per month between four people and reflexively googled nothing. The bus arrived before I could check. Curiosity can be dependant on a lot of resources, time included.

— Gemma Weston

Lost

I always thought they were missing persons, some rumour I’d heard somewhere. They’d impassively watch us beetle up the freeway and we’d grow uncomfortable under their stare and the visibility of it. The missing person thing seemed believable because there was something in these images that suggested they were missing – something unquantifiable shared

by the Faces and the endless rotation of people that used to pop up on Crimestoppers during the news. They lacked something, as if being missing had retroactively tainted all images of them, changed the colour or contrast somehow.

In Autobiography of a Corpse, Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky diagnoses his protagonist with ‘psychorrea’, or ‘soul-seepage’ – a psychic ill that spreads through society; the loss of the ‘I’ by failing to integrate with the ‘we’. The faces were intended as a way to deflect this; plug the hole in the spiritual levee – a composite of images, designed to show the role of individuals in making the community. Perhaps that missing-ness they carried shows that it did the inverse; the uncomfortableness of the Faces comes from them presenting back to us what it was that we are missing, or what is in the process of being lost.

— Jaxon Waterhouse

Vale Faces of the Community

That Janus-faced icon,

the sum of our parts

though we’d rather not admit it.

Surely proposed to celebrate

and boast our best features,

you fell short but gave more.

A totem in transit

of a clan of commuters,

by carriage or car.

Youthful in the morning.

Aged at night.

Always slightly marred.

But like so many before,

who have craned their necks skyward,

we too have been humbled

by a deity built

of our image and likeness,

since met with contempt.

— Harry Price

They look like they have no history to them,,,,like they showed up all at once. They look …like what art ,,always wants to look like. Is that what we are in pictures!?? Is what we are …in pictures almost real? A medium of communication...is not in the photograph; the meaning is in the Instagram...!

In Autobiography of a Corpse, Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky diagnoses his protagonist with ‘psychorrea’, or ‘soul-seepage’ – a psychic ill that spreads through society; the loss of the ‘I’ by failing to integrate with the ‘we’. The faces were intended as a way to deflect this; plug the hole in the spiritual levee – a composite of images, designed to show the role of individuals in making the community. Perhaps that missing-ness they carried shows that it did the inverse; the uncomfortableness of the Faces comes from them presenting back to us what it was that we are missing, or what is in the process of being lost.

— Jaxon Waterhouse

Vale Faces of the Community

That Janus-faced icon,

the sum of our parts

though we’d rather not admit it.

Surely proposed to celebrate

and boast our best features,

you fell short but gave more.

A totem in transit

of a clan of commuters,

by carriage or car.

Youthful in the morning.

Aged at night.

Always slightly marred.

But like so many before,

who have craned their necks skyward,

we too have been humbled

by a deity built

of our image and likeness,

since met with contempt.

— Harry Price

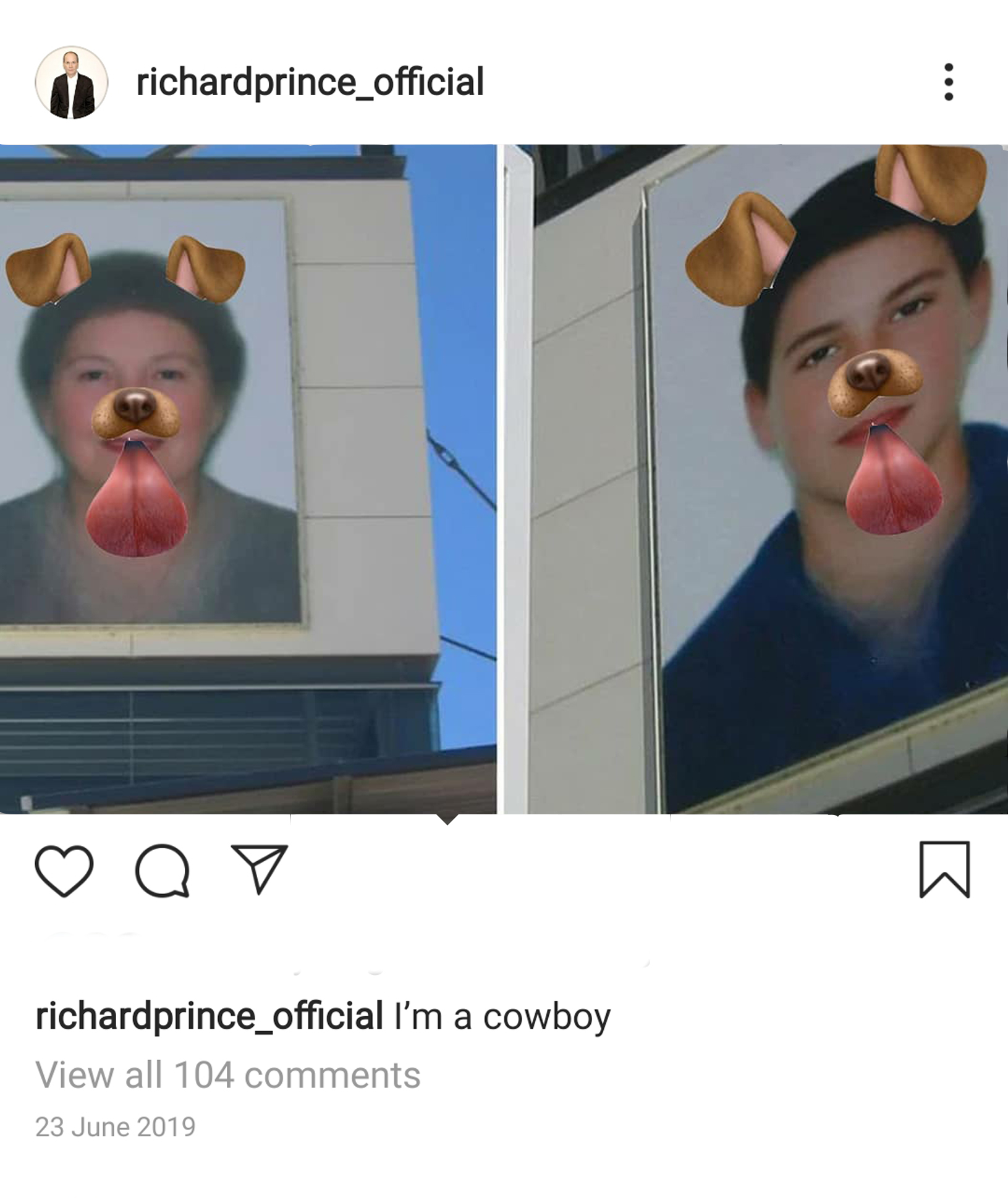

I’m A Cowboy

They look like they have no history to them,,,,like they showed up all at once. They look …like what art ,,always wants to look like. Is that what we are in pictures!?? Is what we are …in pictures almost real? A medium of communication...is not in the photograph; the meaning is in the Instagram...!

I play the camera like a new guitar….I didn't like hovering above myself ,,,and looking back, or going through a door and thinking, how many times did I just go through that door? !!How do I get back? I wouldn't mind people saying, You can't

do this ,,,because this isn't enough. I’m a cowboy!

— Richard Prince

![]()

Success

Dare it be said that the sweepingly popular disdain towards Macron and Glick’s The Faces of the Community, though no doubt contributing to its downfall, may also be symptomatic of the artwork’s efficacy? Its detractors were nettled by the artwork’s “Sauron-esque” gaze, oft-mistaking it for ‘most wanted’ posters in an allusion to the juridical frontal-view mugshot from which the faces are modelled. This anxious response to the instrumentalisation of bodily images as apparatuses of state surveillance is aggravated by the faces’ blurry spectral appearance. In this, we are reminded that these are not images of people but composite entities deprived of interiority, ‘interfaces’ embodying how identificatory images in the digital moment regulate the repressive exercise of law enforcement at a purely imaginary level. The faces of the community are therefore read as the faces of criminal suspects, peering at us with the same disquieting vigilance to which they, and we, are subject. In this respect, its removal is perhaps not a measure of the artwork’s failure, but of its success.

I await with bated breath the day the now-vacant space occupies targeted advertising in what will be the ultimate realisation of our algorithmic identities in an age of privacy mourned.

— Karl Halliday

— Richard Prince

Success

Dare it be said that the sweepingly popular disdain towards Macron and Glick’s The Faces of the Community, though no doubt contributing to its downfall, may also be symptomatic of the artwork’s efficacy? Its detractors were nettled by the artwork’s “Sauron-esque” gaze, oft-mistaking it for ‘most wanted’ posters in an allusion to the juridical frontal-view mugshot from which the faces are modelled. This anxious response to the instrumentalisation of bodily images as apparatuses of state surveillance is aggravated by the faces’ blurry spectral appearance. In this, we are reminded that these are not images of people but composite entities deprived of interiority, ‘interfaces’ embodying how identificatory images in the digital moment regulate the repressive exercise of law enforcement at a purely imaginary level. The faces of the community are therefore read as the faces of criminal suspects, peering at us with the same disquieting vigilance to which they, and we, are subject. In this respect, its removal is perhaps not a measure of the artwork’s failure, but of its success.

I await with bated breath the day the now-vacant space occupies targeted advertising in what will be the ultimate realisation of our algorithmic identities in an age of privacy mourned.

— Karl Halliday

Faces of the Community (2006)

Marco Marcon & Rodney Glick

Cockburn Central Train Station

2006 - 2019