Objectivity & Language:

the power of empathy in audio description

29 February 2020

Mayma Awaida and Tony Sarre

A conversation about audio description and John Prince Siddon‘s exhibition All Mixed Up

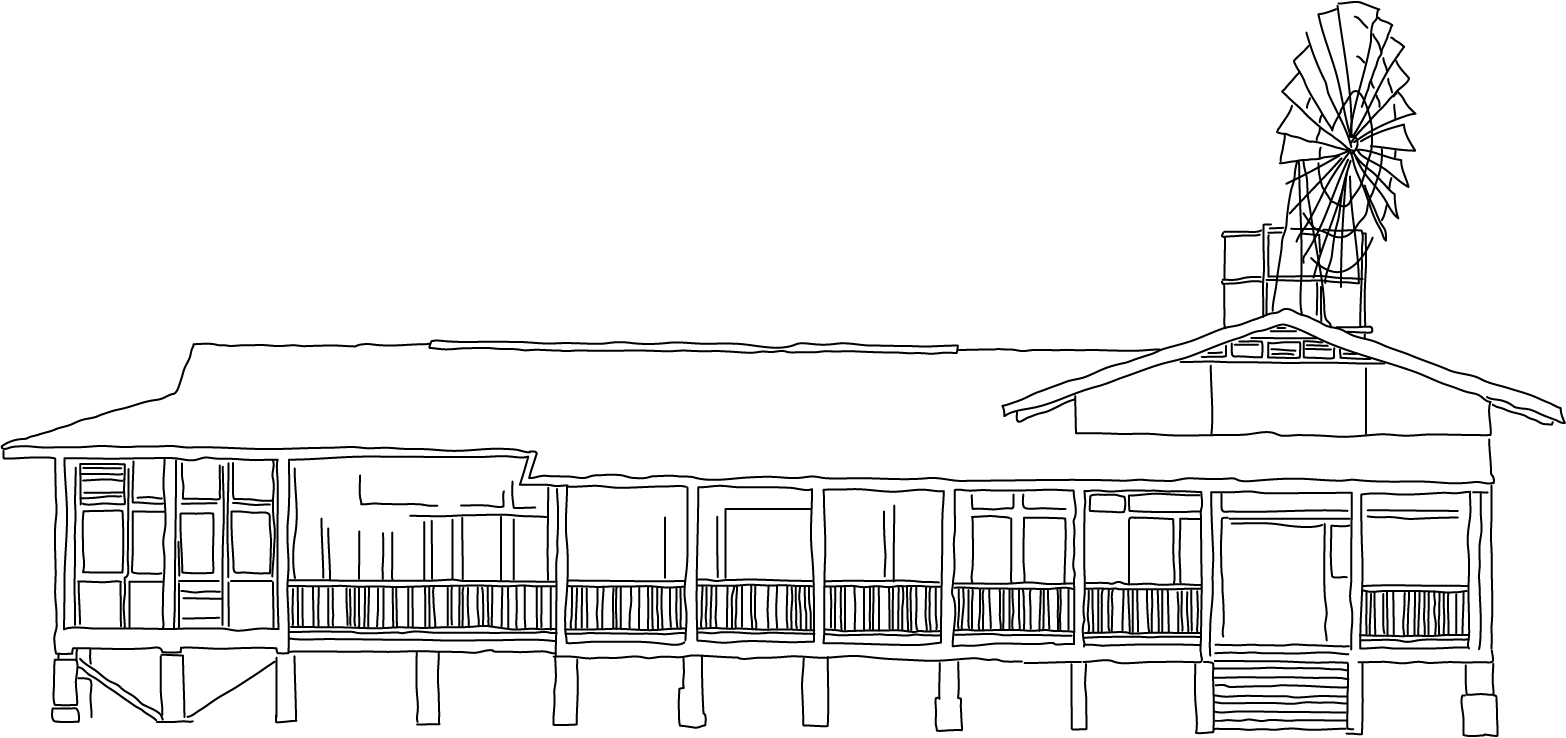

Fremantle Arts Centre

How do we communicate with each other? How can we subvert the ocular centricity of the “visual” arts? How can we create audio descriptions that are about more than accessibility, that are about further and more meaningful understanding, that are about enriched connection?

In Objectivity & Language: the power of empathy in audio description Mayma Awaida and Tony Sarre discuss the language of audio description in the context of John Prince Siddon’s All Mixed Up at Fremantle Art Centre. Mayma and Tony question the didactic way that audio description represents exhibitions and instead argue for the inclusion of abstract and speculative as well as literal narrations. This is the first in a multi-part series in which they will examine disability culture and the arts within a Perth-specific context.

Mayma and Tony have been collaborators for two years. Tony is a script writer, director and film maker. His current body of work centres accessibility and the arts. Mayma is an Australia-Lebanese first generation immigrant, and writer and producer specialising in critical theory and identity politics.

Mayma and Tony are both participants in the inaugural Perth Festival Visual Arts Writing Group, which is convened by Semaphore editor Kelly Fliedner. Objectivity & Language is presented in association with the 2020 Perth Festival, and is supported by the Visual Arts Program Partner Wesfarmers Arts.

In Objectivity & Language: the power of empathy in audio description Mayma Awaida and Tony Sarre discuss the language of audio description in the context of John Prince Siddon’s All Mixed Up at Fremantle Art Centre. Mayma and Tony question the didactic way that audio description represents exhibitions and instead argue for the inclusion of abstract and speculative as well as literal narrations. This is the first in a multi-part series in which they will examine disability culture and the arts within a Perth-specific context.

Mayma and Tony have been collaborators for two years. Tony is a script writer, director and film maker. His current body of work centres accessibility and the arts. Mayma is an Australia-Lebanese first generation immigrant, and writer and producer specialising in critical theory and identity politics.

Mayma and Tony are both participants in the inaugural Perth Festival Visual Arts Writing Group, which is convened by Semaphore editor Kelly Fliedner. Objectivity & Language is presented in association with the 2020 Perth Festival, and is supported by the Visual Arts Program Partner Wesfarmers Arts.

[AUDIO TRANSCRIPT]

[Intro—a mixture of voices read each line, jazz music plays in the background]There’s a very colourful work that swirls…

… In the centre of the painting is the continent of Australia

… It’s made up of lots of little dots in the background

… It almost looks a bit Loch-ness-y

… There are spiders – redback spiders

… Kind of looks almost like a witchety grub

… The shark has a red eye that looks fairly menacing

… and in its mouth, is a man in a canoe.

[Music softens as Mayma reads the introductory text]

[Mayma]Even in its terming, ‘visual arts’, there is an implicit bias that sight is the predominant way of interacting with and understanding art. Yet this is contradictory to the very principles which drive art forwards; art seeks to share, to understand. Art has the potential to unite and invoke discussion across a range of diverse groups, with diverse lived experiences, however, the lack of narration in audio description pushes art further towards occularcentrism and continues to separate the community. In many ways, audio description is still in its infancy, and excludes the lived experiences of individuals who rely on it as their key mode of engaging with art.

Hi, I’m Mayma Awaida, and today I’m in conversation with Tony Sarre, and we’re gonna be talking about how to extend audio description to be more engaging and inclusive.

[Music fades to nothing]

[Mayma]So Tony, historically the language in audio description aims to be as objective as possible, what do you think?

[Tony]Historically audio description has always been keeping it as objective as possible. In some circumstances that’s what you need; you need to have it simply giving you a basic description of what’s in front of you. Unfortunately, when it’s something like a film, or something like a piece of art or sculpture, you need more than simple words. You need to have some sense of what the meaning is.

[Mayma]Right. And like you said, while there’s definitely you know, a place for that - you know, it’s really important for someone that can’t necessarily engage in the work the way we assume everyone can - its losing some of the essence, and ultimately the consumer is the one that suffers, because they lose some of the humanising qualities about the art.

[Tony]Unless we have context, we have no meaning. And when all you’re doing is objectively giving out instructions or words such as: “there’s a cat, there’s a dog over there, there’s a bird here”, you’re missing out on what the artist is trying to say. More to the point: you’re missing out on what a sighted audience is actually gaining for themselves, and we are just left behind really.

[Mayma]And that’s kind of the main point really, isn’t it? Because what we’re discussing today really is, you know, art aims to do several things but I guess one of the main things is that it aims to make meaning or make understanding of the different kind of phenomena in our world, whether that be, sure, literal, but also you know, abstract, or speculative.

[Tony]Exactly. It’s what an individual brings to the actual party. You know, if I’m with you Mayma, you’ll come from young female woman, with certain knowledge and understandings of the world around you. So, you’ll bring that to any description that you give to me, so I’m gaining a lot more about this particular piece of art by you imbuing it with your understanding of the world, than I do with simple descriptions.

[Mayma]Yeah, I think that’s a really good example because, as you said – there are so many ways to audio describe something, but really what we’re trying to renegotiate today is that the culture of audio description kind of places those different styles on a hierarchy, where the most objective, literal thing, is what we value the most. But that isn’t necessarily what gives you as the consumer the most meaning.

[Tony]Yes. And I believe it’s as much as anything, trying to give respect to the blind person. This sense of objectivity; allowing a blind person to make up their own mind about what something is supposed to be saying, what it means. Unfortunately, it’s not necessarily a system that will work. Because without the cultural understanding, the linguistic understanding, the gender, the disability, the whatever you’re bringing to this particular description, I will not understand it. I will not be able to give an accurate analysis of what this piece is. I won’t be able to say whether I like it, or I don’t like it, because I’ve not got enough language. I’ve not got enough context to make a valid opinion.

[Mayma]And yeah, while it is important to be objective, as we’ve been discussing, our opinions and our tastes don’t necessarily reflect that – they don’t exist in a void. Rather, the way that we are sharing a particular experience or a story, actually says quite a lot about the particular context that we’ve respectively come from.

[Tony]Exactly. And I think from, uh, my point of view, I’m the one that gains a lot out of people giving me their stories, their view of the world. I’m learning how they as human beings perceive this piece of art, but just also, how they perceive the world. And I can get as many different people to give me their view of this one piece of art and I can shape my understanding of this based upon multiple opinions, multiple views of the world, I’m not stuck with my own rigid opinions about how something is or isn’t art.

[Mayma]Yeah… so, in a way… the character of the person infiltrates the way that they describe and share an experience. And that comes across in audio description. And that character is constantly shifting.

[Tony]Yeah, actually, we do as human beings. We perform very differently in different circumstances: when we’re ‘round our family, or when we’re at work, or when we are at an art gallery or at a… film festival, or whatever the case may be! We perform differently. But when you are placed or faced with something such as a piece of artwork that performance takes on a different meaning. It takes on a more personal – I think – understanding of what this particular piece of work is, and how it relates to you as an individual. You know, where do I come from? What’s my story? What’s my baggage? And… cultural baggage, social baggage, you know. And that you take that to that-- by sharing that with somebody like me, you’re increasing the overall knowledge of the world, both for me and for the person that’s actually giving the description ‘cause, they’re having a dialogue with the art, but they’re also having a dialogue with me as a blind person. And for me, that’s pretty remarkable.

[Mayma]And that’s really why we’re trying to renegotiate the format of audio description, isn’t it? So that audio description can kind of demonstrate more of those ways in which we are performing versions of ourselves that are attributing particular meanings to art.

[Tony]But I actually think it’s more – it’s the connectivity that I personally appreciate, and I think it’s the power of audio description done, done with empathy. Because you need empathy for audio description to be truly efficient and to be truly connecting with each other. I need to understand the world through you. I need to understand them; I need to feel what they feel, I need to see what they see. I won’t necessarily like a piece of art because somebody else likes it, but I won’t dislike it either because I’m drawing upon them and their experiences. So that—something that if I could see, I might not like it, but because I can’t see, I can actually like something, I can appreciate it based upon what I’m working with somebody else.

[Mayma]So the Perth Festival is currently happening, and we both felt really drawn to the John Prince Siddon exhibition, All Mixed Up, which is on at the Fremantle Art Centre.

[Jazz music interlude plays as Mayma reads written text passage]

[Mayma]All Mixed Up is a major solo exhibition featuring newly commissioned paintings and sculpture from John Prince Siddon. A Walmajarri man based in Fitzroy Crossing in the West Kimberley, Prince Siddon combines diverse influences drawn from television, the traditional Kimberley craft of boab nut carving, desert iconography and the epic characters of the Narrangkarni (Narrangkarni meaning, Dreamtime). Surreal and kaleidoscopic at first glance, these works offer an incisive commentary and essential perspective on the political and social issues of today, and on Western Australia’s dark and mostly undocumented history.

[Music fades to nothing]

[Mayma]So why were you drawn to the work, Tony?

[Tony]Initially, and somewhat ironically, it was because of a visual memory of Fitzroy Crossing. When I was a teenager, I spent quite a lot of time on a cattle station in the Kimberleys, and I would go backwards and forwards to the Fitzroy Crossing, where this work comes from. And my memory of that place basically tells me that it’s a pub, a post office and a general store. And the idea that it’s suddenly become the cultural centre of the Kimberleys is astonishing to me, and that drew me immediately, because I drew visual references, cultural understandings of that location. And it-- it was a juxtaposition to this colourful, involved piece – and by the sounds of it, it’s not the only piece of art that’s coming out of the Kimberleys, or out of the Fitzroy Crossing.

[Mayma]And that’s actually one of the reasons that I also was drawn to the work, because of how, I think, visually exciting it is. And I thought it would be an interesting thing to talk to you about. Actually, um, I’m wondering Tony: did you seem to understand that kind of visual aspect to the work when it was described to you?

[Tony]Yes, I got a strong sense of the colours in particular from people describing this artwork to me. I didn’t quite get a solid understanding - it was a difficult piece to understand or to quantify, I think, is the-- is the word. Because, it’s got such a broad spectrum of qualities to it and it makes it difficult for someone to just say what they’re seeing, what they’re feeling, especially when they’re restricted by the language of audio description as it’s spoken, as we… at the moment… it makes it very difficult for somebody to simply tell me what they see and what they feel, when they are still drawing upon historical audio description, and just giving me words.

[Mayma]So, I think what you’re saying is that when the work was kind of being described to you, there was like, I guess, no particular focal point. There was, like there was a sense of busy-ness with the work, um, maybe even a sense of hesitation in what kind of language to be using. And I’m wondering if that actually acts in a way for you - hearing the way that people are describing it - whether that gives you any particular insight into how we form tastes in our culture?

[Tony]Yes, it does actually! When somebody speaks, they will intonate, or they will hesitate. And I immediately understand that those intonations, those hesitations, they’re informing me what they’re thinking of this work. ‘Oh, I don’t like this work’, because their voice loses, loses they, the vibrancy, that I would gain from somebody who absolutely adores this piece of work and they’ll sit there and they’ll rhapsodise about it, and I get caught up in that. And at the same time if somebody doesn’t like it, I can sense that, I can feel it straight away. Or if they don’t know how to articulate then I pick that up as well. And in those situations, then I will try to help, I’ll ask questions. ‘So, what does it mean to you? What are you feeling?’ you know, so that I’m trying to actually learn audio description, how to engage with someone, how to teach them to audio describe to me. And it’s an ongoing process.

[Mayma]And this work was probably quite an interesting one to choose because I think looking at it myself, I can see that there are quite a lot of elements to it that reference other visual cues that we have seen time and time again in our culture. And each of those visual cues are in itself referencing some other kind of visual cue, and the chain kind of continues. And I think what that’s been pointing to, really, as we’ve been saying this whole time is that our culture is hugely occularcentric. We really take for granted that people who are sighted are able to deduce cultural meaning by unpacking all of those subtle cues but that’s kind of what we’re missing out on with audio description.

[Tony]The limits of what we know of as audio description completely lose out on all of those cues that you were just pointing out. You know, just something as simple as calling something ‘bubblegum pink’, you know, it’s a-- it's a cultural reference. They will see that colour, they will understand it, they will identify it for something that relates to them, but they might not say that to me, they’ll just say ‘pink’. And it means nothing. So, the more educated that we become in educating our audio describers – also educating our Blind, in-- to be more demanding. ‘Well you know, I want to know this, what do you think, where’s this coming from?’ you know, that I think will learn a lot more and we’ll have a lot more communication between people who want to enjoy a piece of art together.

[Mayma]Right. And that kind of takes us back to what we’ve been saying earlier, where there is obviously a place for objectivity in audio description, but really, what we’re kind of losing here is including Blind people in a much wider conversation about social commentary and cultural understanding.

[Tony]The language of audio description shouldn’t be static. It should be organic, and it should be-- it should be changing all the time. Like any form of language, like any form of understanding, it needs to evolve, and it needs to fit the particular scene in which we find ourselves in. If we’re just out on the street and someone’s giving me an audio description of a street scene, they can be as literal as they like – and I prefer it to be literal. But if I’m standing in front of a poster, I want to-- to give me what they think. And we do that naturally, when we talk to each other. We simply don’t do it when we’re talking to a blind person. We fall into patterns of behaviour, and need to we sort of lift out of those patterns, and start sort of, thinking more about how we’re going to communicate.

[Mayma]And I guess, you know, it’s important to say here: we’re not trying to literally change audio description in its entirety. You know, this is really more just about considering how we can extend audio description and make it… like a more inclusive language for both reading art, but reading human response to art. Because at the moment, audio description is really focused on making, like, service accessible, whereas we’re hoping to kind of move audio description towards a language which is more grounded in connection and the essence of like, someone’s character, or a work.

[Tony]Exactly. I want audio description to become more than simply accessible. I want it to be understanding, I want it to be connection with another human being.

[Jazz music fades in as Mayma and Tony conclude their conversation]

[Mayma]Well, it’s been great talking to you Tony. Uh, thank you, and enjoy the rest of the festival!

[Tony]It has been a good conversation and I certainly will have a good time at the festival.

[Outro—read by Mayma]Presented in association with Fremantle Arts Centre and in collaboration with Mangkaja Arts, All Mixed Up is a free event shown at the Fremantle Arts Centre from the 5th of February to the 22nd of March, and will be accessible by wheelchair. Tony and Mayma have been collaborators for two years. Tony is a scriptwriter, director, and filmmaker whose current body of work centralises accessibility in the arts. Mayma is an Australian Lebanese first-generation immigrant and writer and producer, specialising in critical theory and identity politics.

[Musical outro continues]

All Mixed Up — John Prince Siddon

Fremantle Arts Centre

8 February - 22 March 2020

All Mixed Up is curated by Emilia Galatis and presented in association with Perth Festival and Mangkaja Arts.

Installation image courtesy Fremantle Art Centre. Photography by Pixel Poetry. Copyright courtesy John Prince Siddon.

Also see a response to John Prince Siddon‘s exhibition All Mixed Upby Darren Jorgensen on Semaphore here.

Fremantle Arts Centre

8 February - 22 March 2020

All Mixed Up is curated by Emilia Galatis and presented in association with Perth Festival and Mangkaja Arts.

Installation image courtesy Fremantle Art Centre. Photography by Pixel Poetry. Copyright courtesy John Prince Siddon.

Also see a response to John Prince Siddon‘s exhibition All Mixed Upby Darren Jorgensen on Semaphore here.